Where to begin? Perhaps a frank admission on the critic’s part, to serve as a premise to get underway? I’m deathly afraid of sex. That’s why I don’t usually write about it, silly!

Yes, yes, let’s get down to the proverbial brass tacks, shall we? Just the kind of problem that demands attention. It’s not going to get better on its own. So, I started a podcast recently on the topic of extraordinarily horny '90s comics. Bad girl comics, even. Confronting the problem head-on, making the discomfort a topic of conversation. That’s what critics are supposed to do, isn’t it? Sit down with a problem and worry it to death all over the page. What is criticism if not a transcription of an encounter?

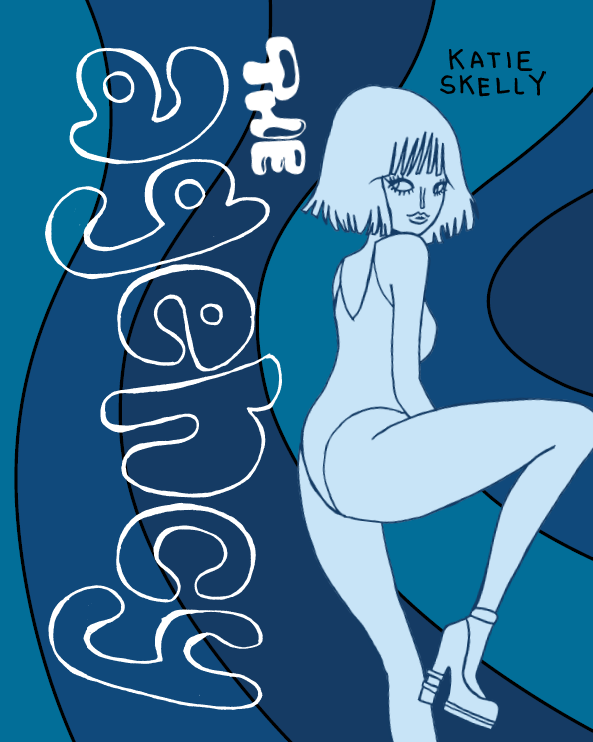

Skelly knows how to work with a plot. Maids (2020) has a plot. My Pretty Vampire (2017) has a plot too. But The Agency is our main course today, reissued by Fantagraphics this past April following a previous version Under the FU label five years ago, collecting comics mostly serialized online from 2014-2017. There's a new story too. Now, I’m no publishing magnate, but it seems to me that going back into print with a completely updated package is a good sign. Must be some demand.

Interesting to note: I think it’s a sure bet that if Skelly had brought this book to Fantagraphics 30 years ago, it would have shipped under the Eros banner. Eros no longer exists, but the company evidently has no compunctions about printing sexually explicit material in 2023. It’s certainly not restricting her popularity. She’s even got a podcast herself.

Well, anyhow, I hope you weren’t expecting some kind of contrarian takedown. It’s a good book. An interesting book. Apparently also a popular book. It’s filled with explicit fucking. Like, bro, Spider-Man is here, and he’s doing stuff you didn’t know Spider-Man could do. But there he is, flying through space with his face in that nice woman’s ass. What a country.

Now, casting a spotlight on the sexual proclivities of Disney properties is a classic move. People have been sued for doing just that thing. People have lost jobs. Some of it has even been weirdly interesting. Google “Wally Wood Disney” sometime, if you don’t know the reference. Just, uh, not from a work computer. But we’re not reading Goodman Beaver here. Spider-Man doesn’t show up for any kind of heavy-handed satirical beat, I don’t think, he just happens to be flying through space for his encounter with "Agent 8," then he's bugging right out to go finish whatever he was doing. The late, great John Romita’s greatest contribution to the Spider-Man mythos was the fateful admonition, let’s put more pretty girls in it. Skelly clearly agrees that it’s OK for Spider-Man to be a little bit sexy.

Agent 8 apparently spends much of her time flying through space, having sex with Spider-Man, getting spitroasted by magic mushrooms, and teasing her skeleton pal. The touchstone, for this section at least, is Barbarella. And I don’t mean the 1968 movie (although that’s certainly a very fine film), but the comic by Jean-Claude Forest. Originally serialized in V Magazine in 1962 - yes, shocking coincidence, the exact same year our friend Spider-Man first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15. Humanoids published a nice translation of the first couple Barbarella stories almost a decade ago, adapted by Kelly Sue DeConnick; well worth your time if you’re unfamiliar with the source material. (The lettering is terrible, but that’s practically a universal constant for translated editions.)

That series certainly had a reputation for sexual explicitness - perhaps slightly exaggerated in the fullness of hindsight. It was French and had naked ladies in it, yes, but Little Annie Fanny was far more frank in terms of showing off the proverbial goods. Barbarella had a whole lot of plot to wrap around the occasional sequences of the title character walking around with no clothes on. The most interesting aspect of the series, at least to me, is Forest’s line: 'consciously tentative' is the word I’d use. It’s an ink line with the weight and character of a pencil sketch. It almost makes you think he was drawing freehand right on the page, but I doubt even the French would be that louche.

That ink line is important here. The timeframe of composition for the stories in The Agency means that the reader can track a significant evolution in Skelly’s line across almost a decade of work, beginning with the original clutch of stories and leading to the most recent addition. Her style changes. Her line loosens considerably, from what already began as a loose default. It thickens.

Get up from your chair, please, and pull down from the shelf your copy of Nurse Nurse. Sparkplug Books. The first of those comics was from 2007! That was a while ago; we were never younger. Notice what she’s doing there? A steady line weight. That’s a pen. I must admit, I’m surprised to find so much Ron Regé in the work of the generation that immediately followed. He started to make himself felt around the time I was at the height of my ardor for Fort Thunder. There’s only one artist I’ve ever bought a print from, and I’ve bought more than one print from Mat Brinkman, but Skibber Bee Bye (2000) and Yeast Hoist (2003) really hit with people. Certainly more than I credited at the time. Honestly, at the time I found Regé cloying, which says as much about me as him. You can certainly see that era of indie comics marked very clearly on Skelly’s earliest comics, that mid '00s sterile line familiar from era-defining work by the likes of Kevin Huizenga and Chris Onstad both. They both took a lot from Chris Ware, clearly.

Skelly outgrew the fixed line weight, in time. However, that points in the direction of another singular influence, John Porcellino. That didn’t occur to me initially, perhaps because the two artists' respective subject matter is so divergent. But then I glanced at Nurse Nurse and it really jumped out. And from there, I think, even as her line has become more organic and incorporated color, Skelly retains a piece of Porcellino’s stillness, his commitment to the flatness of the picture plane. Even when that stillness might seem in conflict with the fervid exigencies of horny art: we’re never quite as free to give rein to blank desire as we’d like in a Katie Skelly book. The distancing is intentional, occasionally even spooky.

The most dissimilar strip in the book is the “Agent 73” sequence, written by Sarah Horrocks (the only other creator credited for the collection). It seems a lot looser than the rest of the book, practically crude in places. An imprecision that would have been alien to the Skelly of 2007. There’s your Forest. These pages also feature the most riotous use of color. They appear to be colored by hand, possibly even by felt tip pen. Spontaneous beyond reason. She could do a whole book in that kind of high vatic state, I wouldn’t mind.

Elsewhere in the book, Skelly's sense of color is far more controlled. Take “Agent 9”: colored as simply as possible, one supposes. There’s lots of negative space on the page to fill with flat color, bright and bold and practically garish. It’s vivid and composed, very Kris Kool. The strip is based in a familiar milieu to anyone who’s ever seen a movie: high fashion modeling. People driving cars and having sex on the beach. Flip the page to “Agent 10” and the primary colors are gone, replaced by crimson and mustard and teal. We’re not taking drugs on the beach with fashion models anymore, we’re in the middle of sadomasochistic rituals involving octopi and the gift of prophecy. The vibe has shifted.

The shifting line, color palette, and tone of these stories points in the direction of a formalist challenge. Each section inhabits a different genre space, be it frothy sci-fi, horror, fantasy, or heavy drama, and each of these sections inhabits a different aesthetic location. Whatever the remit of the amorphous Agency, under these circumstances it amounts to a general admonition to go out into the world and assume a role in some manner of an erotic proceeding. So we see, there’s an interstellar agent living out a Barbarella fantasy, and another agent modeling swimwear, and another agent reenacting The Night Porter.

But these stories are still all about the same thing. Sex isn’t a metaphor here, not a thematic extra, not a component in any other kind of story but a story that’s explicitly about fucking. The emotional register of each story changes, but in each instance we’re given a character study of sorts. Characters reveal themselves in the process of doing and, er, being done. I’m really not one for writing maxims such as “show, don’t tell,” but if there’s any insight to be gleaned from the imperative, it surely rests in the understanding that—from the perspective of the consumer of fiction—watching someone do something interesting is far more revealing than listening to them talk about doing something interesting. Gives the audience more to work with.

The Agency is a central pivot point in Skelly’s work for the simple reason that, while just about everything Skelly does is concerned with sex in some way, this is the only volume explicitly about sex without recourse to other exigencies. Maids, for instance, is a book with a definite erotic charge, but it’s also a book that ends with a woman’s eyes being popped out of her head in a blood-drenched foyer. My Pretty Vampire is very explicit about the connection between sex and death in the vampire mythos. It’s also interesting for presenting vampires not merely as monsters but as uniquely vulnerable - fragile creatures, to some degree, if also capable of terrible overpowering violence. Sex is incidental to that violence.

Skelly’s latest, Heaven, like pretty much all of her books, is being serialized in serial pamphlets - if you can believe such a thing. What’s next, variant covers? (Don’t worry, she's done those too. She did a variant for Valiant’s The Death-Defying Doctor Mirage in 2015, and boy am I surprised to be mentioning Valiant right now.) In any event, Heaven appears from the evidence of the first few chapters to be a definite horror story. It’s about a mysterious phantom strip club on the edge of town that half the town can never seem to find, despite giant neon legs thrusting into the night. It’s probably about vampires, or something like vampires.

It’s definitely about sex too, don’t get me wrong. Dolly, our protagonist, is so entranced with the idea of becoming a dancer at Heaven. The most horrifying sequence in the story so far—perhaps in Skelly’s entire oeuvre—is Dolly taking a pair of pliers to her teeth in order to remove her braces, all so she can get that job.

Howsoever Dolly becomes fixated, she certainly doesl in the space of a few pages, she is pining for the opportunity to dance on that stage. Perhaps it's the intimation of freedom, of expression? Perhaps vampiric coercion? Heaven doesn’t seem a particularly abusive type of establishment. The bouncer is a woman, and she’s not afraid to take pests out into the desert and stomp them to death. It almost seems a welcoming environment, for a young woman having what is clearly a species of sexual awakening. Except for the fact that they’re also clearly some kind of mystical murder cult. Possibly vampires. Pobody’s nerfect.

Running through all of Skelly’s work is candor around the topic of sex. The ultimate expression of this is, of course, The Agency. There’s a degree of candor in all erotic expression that isn’t purely mercenary, inasmuch as any expression of lust demands some manner of obeisance to desire, and desire is a doorway into the most vulnerable part of a person.

Of course, there’s also something disconcerting at play here, as well. There’s that Porcellino-tinted stillness erecting a glass wall between the subjects of these stories and the audience. Then there are the antecedents to Skelly’s occasionally detached vivisection of these well-worn exploitation genres. I think in this respect Skelly reveals herself as an heir to Richard Sala, someone else with an eye towards placing a certain kind of woman in a certain kind of detached genre pastiche. Just update the references a decade or two - Skelly is more Hammer Films and Dario Argento than Lon Chaney and Fantômas.

Cartoonists reveal themselves in their objects. Certainly we all know what Milo Manara likes. He likes ‘em skinny, he does - and lithe. With a dull blank stare, even. If you’ve read one Manara story, you’ve read a great many Manara stories in terms of the variety of women on display. John Romita, may he rest in peace, was really quite fond of shapely calves, and you can’t tell me that didn’t imprint on a generation of readers. No comment! Kirby liked them fairly strapping, as does Crumb. In all honesty, I believe we actually know way too much about the kind of woman Crumb prefers. Michael Turner had a thing for swimmers.

If there is such a thing as a “Skelly girl”—and I posit there is—she’s young, vaguely ethereal; what might in another era have been called a nymph. Her body is 4/5 long legs by volume, which occasionally leads to some uncanny anatomical effects. Not really my type, to be blunt, but certainly a recognizable cultural avatar, barring the artist’s proclivity for those odd little noodle noses. Nevertheless, it's all an immediately legible signifier of sexual desire. More to the point, the Skelly girl is confident. Very much the master of her own desires. Diffident, even, such as the fashion model who has the drug orgy on the beach. It’s that self-possession that lingers in the memory. That’s an enviable sensation: self-possession enabling expression.

It seems a kind of generational more, if you’ll forgive the half-baked generalization. Perhaps it's purely a consequence of growing up with the internet; I’m smack in the middle of the last cohort to grow up without the internet, you see, as the World Wide Web was just coming into focus around the time I graduated high school. The distinction probably dwells more within my imagination, but I know for a fact that people younger than me tend by and large to be more reflexively open about sex, especially in online spaces, whereas people older than me tend not to be. I have often felt a kinship with Philip Larkin, in regards to being just a little bit too old to fully inhabit the era swirling at my ankles. Born too early for that brilliant breaking of the bank, terrified beyond reason at the expression thereof.

One reason, perhaps, why The Agency seems to me almost a kind of bellwether, an artifact of this moment in time. A book about sex that takes as its first principle the idea that sex is a topic worthy of interest and not merely passive admiration. It takes sex seriously. There’s much ado regarding the disposition of sexy art, these days, to judge from the discourse surrounding the very notion of sex scenes in movies. It’s not a coincidence that the rise of this burgeoning neopuritanism is also happening at a time of unprecedented consolidation of all human media under corporate control. People who have a lot of money tend on balance to be reactionary shitbags who hate any and all expressions of sexuality. Sexual freedom is a corrosive influence for authoritarians.

Incidentally, they’ve spent so much time and effort lately ginning up hatred of queer people that it’s sort of flying under the radar that the right is also talking about pornography again. They’re pushing (incredibly unpopular) pornography bans. It’s only a matter of time before they take aim at the extent to which sex work has been normalized in recent years. They’re laying the groundwork as we speak. I hope I’m wrong but let’s check back in six months and see where we stand.

In that light, a book like The Agency takes on a new kind of significance. The asinine antics of rampaging puriteens certainly cured me of any desire to remain a curmudgeon on the topic of sex. Turning personal hang-ups into political hay is a useless way to live your life. Standing up to reaffirm the primary significance of the erotic as an arena for personal expression seems a genuinely necessary act, even a liberatory act.

For so long as there remains no more dangerous act than fucking, the work of Katie Skelly will continue to read like grabbing an electric wire with your bare hands.

The post That Brilliant Breaking appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment