A man reads the manuscript to a book slated for publication, and encounters an image familiar to him. It's from a recurring dream of the book's protagonist, in which a primitive man crouches by fire, surrounded by corpses. "This dream haunts the character," the reading man narrates, "and he comes to wonder if there's some kind of shadow-self living inside him… And if the dream is its cry to be set free." He looks to one side of the aircraft in which he is seated, takes a drink. "Like I said, it was a strange book... But the strangest thing was… I used to have a dream almost exactly like that."

It is this sequence that more or less opens Night Fever, and the latest outing by comics' old reliables, Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips, does not get any deeper or more subtle from there. The story of a book market professional on a work trip to Paris, abruptly driven to escape his alienated life in favor of a brief adrenaline rush running wild through violent streets, this standalone graphic novel makes its components clear: a mixture of After Hours' chaos-in-a-newly-alien-urban-nightscape, Eyes Wide Shut's rich-people-decadence-gone-wrong, and the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde's… Jekyll and Hyde-ness of it all, I guess.

That's where the problem begins. It is not that Night Fever wears its forebears on its sleeve, but that it is, fundamentally, nothing but sleeve. I think it's not outlandish to claim that Brubaker and Phillips, by now, do not exist within American comics so much as in parallel to it. Having worked together almost continuously since 1999—that's one year more than I've been alive, dear reader, so I am not old enough to remember a world where "Brubaker/Phillips" wasn’t as much of a brand name as Coca-Cola—I suspect that any claim to profound realism on the part of this duo, one that actively engages with the externality of the rest of the world, has long been forfeited. In his afterword, Brubaker recollects:

After doing five of the Reckless books in two years, Sean and I needed a break, which for us means not actually taking a break but doing a different graphic novel instead. And for a long time Sean had been asking me to write something set in the UK or Europe, so he could draw places he actually knew, as opposed to recreating the secret history of Los Angeles on paper.

This is precisely where the duo struggles; there is nothing to distinguish Night Fever from any of their recent outings. Paris does not feel too different from Los Angeles, except in the occasional and positively Claremontian peppering of merde and oui, and the 1978 period setting hardly diverges from any other year. Having fully sunk into their creative comfort zones, Brubaker and Phillips appear not only to have forgotten the existence of any zone outside of it, but to have projected a similar stagnancy, extra-temporal and extra-geographic, into the lives of their characters. And they do it with such assuredness that, by God, I can't even tell if it's on purpose or not: the protagonists of Pulp (2020), Reckless (2020-22) and Night Fever have all imprisoned themselves in a cognitive ur-past, with Reckless protagonist Ethan Reckless (that's right, that's his name) going so far as to say, "It's hard to explain, but I used to be… more. Now I'm just kind of flat," a disclosure that by now cannot be handwaved as mere coincidence.

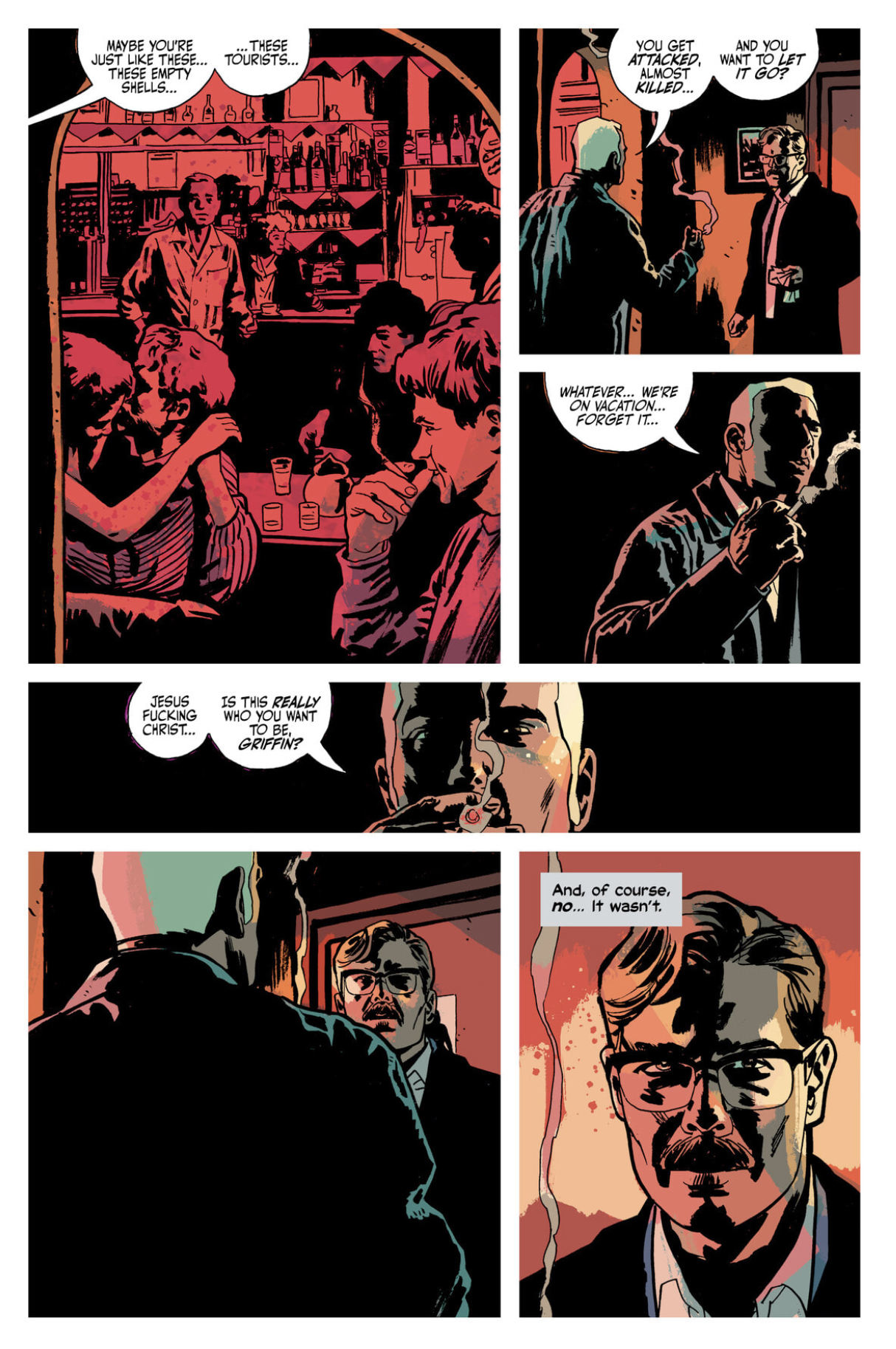

But it cannot be attributed to self-awareness either - at least not an awareness that prompts the creators into action. Night Fever may be the thinnest Brubaker/Phillips project, hanging onto existence by force of habit alone; none of its ideas are fleshed out enough to plausibly extend past the confines of immediate plot action. Every component of this book gives the impression of vanishing the moment it is off the page. This is most evident during the protagonist's second "night out" sequence, in which he fully surrenders himself to the wild life, so utterly drunk and high that he blinks in and out of consciousness, not so much travelling as teleporting across a selection of unlinked moments. He confesses to us, "There are parts of the rest of this night that I'm not sure of..." But the authors don't appear to be sure either, beyond the cop-out of the protagonist being manipulated by a supposed partner in crime - this is a narrative mode that only performs randomness to disguise its profoundly ramshackle nature.

In fact, Night Fever is a book phenomenally lacking in confidence. For a dive into one's own id, an unraveling of inhibitions, there is nothing to show what inhibitions were there in the first place. And when the protagonist declares crime to be "the biggest high in the world," there is not a bit of excitement - highs become indistinguishable from lows, and neither have any standard for comparison. The narration in particular is where Brubaker demonstrates unconditional surrender to his own shorthand: for a tool so dependent on voice, of messenger and recipient, there is no clarity or justification for either. One wonders why this narrator is addressing the assumed reader to begin with, beyond this being the case in all of these books.

Phillips, for his part, is just about the best creative partner that Brubaker could ask for, insofar as his work does not appear to change. He is a rock-solid storyteller and aesthete, whose action is perfectly clear and whose compositions are classically gritty - just as they have been for ages. He too has been trapped in that separate-parallel bubble, wherein he appears incapable of creating anything even the tiniest bit alien to the Brubaker/Phillips oeuvre. True, Paris' cobbled streets and antique buildings have a très historique feel to them, but the atmosphere is subsumed by the Ur-Bru/Phil ethos. Italo Calvino's Marco Polo said, "Every time I describe a city I am saying something about Venice." Phillips' cities do not have a Venice to be anchored by: they exist fully and exclusively in the realm of self-reference.

The star of the show, as has been the case for the past few releases, is a younger Phillips: Jacob, son of Sean, and the latest in a long line of highly-competent colorists charged with Brubaker's and Phillips-the-elder's work. There's a hint of Julia Lacquement in his refusal to portray things as they appear, instead portraying how they feel. And how they feel is like a bad headache: as before, he brings a palette that feels at once faded and oversaturated. His swatches of color do not stay within their dictated contours, stretching across surfaces so as to dismiss their boundaries as perfectly arbitrary. Indeed, under Jacob Phillips' palette, Night Fever's frenzied landscape almost comes alive, but "almost" is as far as it goes.

At the end of the story, on the flight home, our protagonist—shaven, so as to avoid being identified for his Parisian activities—revisits the same book he read in the beginning. Lo and behold, he reads the same chapter, but the ending, miraculously, has changed: "The guy's hitchhiking, but he's also driving a car… And he runs himself over. So the question is, which guy is he…? The one driving or the one lying dead on the road?" This question haunts him as he returns home to his wife, having 'rewritten the story' or something of the sort. Let the record show that I warned you in advance: it really does not get any deeper or more subtle. You turn the page and see Brubaker's afterword. "Sean and I needed a break." Having witnessed their long-term transition from significance to mere signification, I, for one, have no choice but to concur.

The post Night Fever appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment