Ten years ago, I was not planning to attend the first Comic Arts Brooklyn (CAB) event, scheduled for November 9, 2013. However, when Art Spiegelman asked me to moderate a panel about the graphic novel adaptation of City of Glass that would include himself, Paul Auster, Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli, I found myself, ultimately, unable to say no. I first encountered the book in college. It was one of the few graphic novels in the library, and I read it cover to cover, sitting in the stacks. The book was out of print for years following its initial 1994 publication, and I finally found a copy for myself thanks to Alternative Comics publisher Jeff Mason. At that time I was writing a comics newsblog called EGON, and Jeff invited me to relaunch Indy Magazine, his online magazine about alternative comics. Several quarterly issues—and Eisner and Harvey nominations—followed. When I learned that City of Glass would be reprinted, I put together a special issue to mark the occasion with features including a lengthy interview with Paul Karasik that I conducted in Boston. Notoriously press-averse Mazzucchelli even agreed to answer three questions in writing, and generously shared some fascinating previously unseen images, which appear in the text below.

I have been teaching a course on the graphic novel since 2008, and, as I mention in the panel, all of my students read City of Glass. It is, among many things, a self-exemplifying book that teaches the reader how to read it, and in the process can teach many lessons about, as Spiegelman says below, “the anatomy of comics.” My regular engagement with the book in a teaching context certainly prepared me to moderate this panel, but even more, the event offered me the unique opportunity to raise points I make in my teaching within the context of a conversation with the creative collaborators involved who produced the work. Beyond all this, I was very excited to lead a discussion including Paul Auster and Art Spiegelman. I didn’t know Paul A., but I had met him and I knew that he and Art were and are close friends. Various fascinating parallels in their lives and careers occurred to me as I contemplated the opportunity. How could I possibly say no?

The previous year, I had moderated a panel at the Knitting Factory with Spiegelman, Richard McGuire and Chris Ware as part of the final edition of the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival, which I had co-founded and organized with Gabe Fowler and Dan Nadel. Now, I entered that space to moderate the City of Glass panel, presented as part of the first Comic Arts Brooklyn (CAB), organized by Fowler. Tom Spurgeon covered the event in his post-show reportage:

[T]he City Of Glass graphic novel adaptation reunion panel -- featuring Paul Auster, Art Spiegelman, David Mazzucchelli and Paul Karasik -- was delayed about 35 minutes because of technical issues. When it finally went off moderator Bill Kartalopoulos did not have control of the screen like he had during last year's panels. I admired how quickly Kartalopoulos moved the panel along -- not an easy panel to begin with -- considering how much time had been burnt away and the distraction of having to ask for help with every image. He asked a couple of questions where I felt like screaming out Marge Simpson-style "Don't fill up on bread!" because I thought they were extraneous that ended up being the best questions asked of the panel. That guy is really good at moderating.

What follows below is a transcript of the City of Glass panel which took place, principally illustrated with images from the slides I showed while we spoke. Revisiting this event nearly 10 years later, I am pleased that our conversation shows no trace of any technical difficulties we may have encountered that day (in fact, I’d completely forgotten about them). I am proud to have conducted what is, as far as I know, the only published conversation between Art and Paul Auster. This transcript was published in French several years ago in the 5th issue of Kaboom magazine, edited by Stéphane Beaujean, and I’m happy to share it again here, for the first time online and in English. There are a lot of rich ideas in this conversation, which point to the many rich ideas in this magnificent and unlikely graphic novel.

-Bill Kartalopoulos, 2023

* * *

Bill Kartalopoulos: Thank you to everyone for coming out to this panel today. I am the series editor for the Best American Comics series from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. I’m also the programming director for the MoCCA Comics Festival. And I’m the publisher of Rebus Books, a very small avant-garde comics imprint.

And I’ve also had the great opportunity to teach classes about comics for several years, and as I was telling some of our panelists earlier, there was no student who took my graphic novels class who didn’t have to read, study, discuss, and write about City of Glass. For a number of reasons, I think a lot of which are self-evident to anyone who has read the book, which probably many of you have, and maybe some of which we’ll at least touch on today. It’s a book that really exemplifies a lot of the things that comics can uniquely do, expressively, but in a way that proceeds directly from the content as opposed to simply being an exercise or experiment. And the content that it proceeds from, of course, is a novel by Paul Auster, which is also wonderful for teaching purposes because students can compare the graphic novel to the original prose and really see all of the choices that go into making a comic; that comics don’t exist in a state of nature. They’re a product of a lot of intelligent choices. And City of Glass more than most of the graphic novels that have been published over the last dozen years or so is a book that makes all the right choices.

So, since we’re already running late, we have four panelists who probably need no introduction. Please join me in welcoming Paul Auster, Paul Karasik, David Mazzucchelli and Art Spiegelman to the stage.

[Applause]

I actually wanted to start today’s panel with an epigraph from Paul’s work, and this is a quote from “The Book of Memory” in The Invention of Solitude. And in it you’re talking about translation, which you did a lot of as a younger writer.

Paul Auster: Yes.

And you write, about a translated edition: “It is both the same book and not the same book, and the strangeness of this activity has never failed to impress him.” And that seemed to me a kind of apt quotation when thinking about the graphic novel adaptation of City of Glass and the original prose version.

Auster: Well, this is not a translation. This is adaptation. There’s a difference. And I suppose we are all very familiar with this thing called adaptation because of film. So many books that we’ve read have been turned into movies. And as we know, most of these adaptations don’t work. It’s the rare book—good book—that becomes a good film.

So, in this case, I should back up maybe, just a little, and say that Art and I have been friends for a long time. And at some point, 25 years ago or so, he started talking to me about doing a graphic novel. He said, “Why don’t you do it?” And he wanted to start a series, getting novelists to do this. Well, to tell you the truth, I could never get too excited about that idea. I thought about it, but I didn’t really feel the necessity of doing it. And then some more time went by, and then Art said, “Well, I have a new idea. Adapting novels that have already been--”

Art Spiegelman: I gave up on the first idea. The first idea, was, the phrase “graphic novel,” which was irritating me, was coming along. And Maus was out there doing well, and I figured, this company that’s beginning to crowd onto that shelf was mainly Dungeons & Dragons manuals, and I figured we needed to jumpstart this; if it was gonna work as a section of a bookstore separate from the Garfield collections, there needs to be more graphic novels. Ok, I give up, if they’re novels, let’s get William Kennedy and Paul Auster and people interested in doing such things. And the problem was, [first] it’s a rather rarified language, learning how to really make a comic that’s worth making. That’s one problem. And second, if you’re going to learn a rarified language as a novelist, it might as well be screenwriting because there’s a much bigger money pot at the end of it, there’s more glamour connected to it, until very recently. And the result was: everybody was sort of interested until they started looking at what it would involve. You know? And then it was like, “Woah!” And for Paul--

Auster: I never even got that far!

Spiegelman: You were a good hypocrite. You were a very good hypocrite. You said, “Oh, that’s interesting!” I kind of put you together with an artist who loves your work, who’s here today, Lorenzo Mattotti--

Auster: Yeah.

Spiegelman: You liked him, you liked his work--

Auster: He’s a great artist, and he’s a wonderful man.

Spiegelman: And it seemed like, that could be cool. And then the problem became doing it. So one time I’m taking a walk with Paul in Prospect Park, and he says, “I’ve been thinking about your book.” Alright, what’s up? And he said, “Well, I see a little boy hovering above the water.” Huh. “Sounds great, Paul! Get right on it!” So then, I don’t hear about it for about a year and a half again, and then he says, “So I have a new book coming out, would you like to do the dustjacket?” And it’s [laughs] Mr. Vertigo--

Auster: Mr. Vertigo.

Spiegelman: Which has as its central image--

Auster: The boy who levitates.

Spiegelman: So yes, as soon as the idea really ignited, it went back to your language.

Auster: It became words rather than pictures and words.

Spiegelman: And then-- I should say that this started as a bad idea, and then when I gave up, a friend of mine--

If I can pause you for a second, Art. One of the things that is really clear to me before we get into City of Glass, and I think is probably already really clear to the audience, is that you guys are good friends. And that the friendship, I think, was the thing that premised the possibility of this collaboration.

Auster: I have total trust and faith in Art. You see, I knew that if he was initiating a project it was going to be interesting. And there are very few people about whom I feel that way. So then, so we got to, because I’m not going to be saying much more-- so when it was finally determined that the project was now adapting City of Glass, Art said that he had gotten these two terrific artists to do the adaptation. We got together once, 20 years ago. We’re all just appalled that so much time has gone by.

Spiegelman: I was telling people that it’s the fifth anniversary.

Auster: Yeah. Twenty years ago. And I remember sitting around at the table, at Art and Françoise [Mouly]’s apartment, going over the preliminary sketches that Karasik and Mazzucchelli had done, and saying only one-- I was so impressed by the way it looked, I only had one request. I said, “You can take out as much as you want in the book. Don’t add any words that are not in the book.” And they did that. And so even though the language is, of course, very stripped down, there’s nothing that didn’t come from the original. And so I felt satisfied with that solution. And then they went and ran with it. And I really feel the results are brilliant. So let’s hear what they have to say now.

I wanted to back up a little bit if we could, because I was sort of thinking about Paul and Art, about your career trajectories and life trajectories leading up to the point of collaboration a little bit. And it seemed like there were some things similiar about the moment and context in which your work first came to be widely known. One of the things that I learned recently during Occupy Wall Street, Paul, was that you were involved with the student protests at Columbia.

Auster: Yeah, yeah, I was arrested and thrown into jail and part of the big revolution there in 1968.

Yeah, and you appear in a documentary called The Fall that’s about that, and I learned that because a friend of mine was screening that film as part of the Occupy activity that were happening--

Auster: Oh, is that the documentary in progress or an older one?

It’s Peter Whitehead’s documentary.

Auster: No, I don’t even know it. I’ve never seen it.

Oh, you appear in it. Yeah.

[Laughter]

Spiegelman: It was the '60s, you know?

[Laughter]

And Art was also involved in the more, I think, artistic and psychedelicized side of--

Spiegelman: Meaning communes and LSD rather than the front lines and the barricades.

[Laughter]

And you’re only year apart in age, so you experienced this in similar, if different ways, I think.

Auster: Yeah. Yeah. Well, we were talking before about how America has turned psychotic today. Well, I think that was another psychotic moment in American history. And we were so young and vulnerable then, and I’m sure it had an enormous impact on everyone--

Spiegelman: I think it hasn’t been not psychotic for 300 years.

Auster: Well, there are moments of great intensity and that was one of them.

Does that participation in the revolutionary counterculture of that period still inform your response to contemporary political events?

Auster: Without question. I should add, I was not an activist in the sense that most of my time was spent reading books and writing. But I had strong political convictions. And when the moment came to either do something or not do something, I chose to do something. But it’s not as though I spent my 20s as an organizer or activist. But there it was. The moment came and I wanted to participate.

And Art, it seems sometimes when I look at that time, the underground comix had a lot of political sympathies, but kept the sort of political side of the counterculture sometimes at more or less at an arm’s length. It depends a lot artist to artist, obviously.

Spiegelman: Totally artist to artist. But I think everybody’s ambient empathies were the same. You know, like, I would go to all of the protest marches and stuff in the hopes of meeting a nice hippie woman. [Audience laughter] And the Rat [i.e., Rat Subterranean News, an NYC underground newspaper], I tried to work for the Rat, but it was right after they got taken over by feminists, and they kicked off-- they accepted a cover of mine and then didn’t run it. I don’t know what happened. So the [East Village] Other was more sympathetic to a wider spectrum.

One of the things that’s interesting to me, too-- [addressing Auster] you had written a lot as a younger writer, you did poetry and translation, you had an early book that was a memoir, that I quoted from earlier--

Auster: Yes, The Invention of Solitude, yes.

And I guess City of Glass was your first widely-published fiction novel.

Auster: It was the first novel, period. Yeah.

And I’m not sure if my research is 100% right, but it looks like it came out first from a kind of small kind of avant-garde press, and then had a mass market edition.

Auster: Yes, because the book was written-- let’s see, it was published in '85, it was written in '81, '82, and then it was rejected by 17 or 18 publishers. Which, that dragged on for about a year and a half, during which I wrote the second novel of The New York Trilogy [City of Glass was the first] and was well into the third. By the time this small press, Sun & Moon Press took it on, located in Los Angeles, of all things. The New York Trilogy published in L.A., but so it goes. And he did have a very good list. It was, as you say, a small, avant-garde publisher. And for some reason, the books took off. It got noticed, even though the first printing I think was 2,000 copies, the hardcover. And my advances for each of the three books was zero.

In the great tradition of small press publishing.

Auster: So, big-time launch there. [Audience laughter] But still, I’m very grateful to Douglas Messerli, the publisher, because otherwise I was gonna drown.

What’s fascinating to me is looking at the covers of the first small press edition and the mass market edition, it sort of indicates the extent to which it’s kind of a liminal book. The experimental publisher sort of presents the book as if it’s a work of literary fiction, the mass market publisher really pushes the film noir, detective angle.

Auster: Woodblock covers were very popular in the mid '80s for some reason.

There was a kind of weird Miami art deco noir motif at that time.

Auster: Yes. Yes. Yes.

And it’s interesting to see how--

Auster: And that’s the British, the Faber and Faber on the left, that was the first time the three books were published together in one volume.

And I was also fascinated to learn that the book actually won a prize for detective fiction, the Edgar Award.

Auster: No, it was nominated.

Oh, it was nominated.

Auster: Yeah. It was very strange. Because I never thought of it as a detective novel at all. Like, suddenly I was nominated and this same publisher took me-- we all went to this award ceremony, the Edgar Awards, and I remember we went to the Algonquin Hotel after, and he said, “I’m gonna buy you some champagne to celebrate,” and the waiter came and he opened up the champagne and he poured it all over me. [Laughter] A firehose of champagne. My one jacket and my one tie. [Laughter]

Spiegelman: Baptized.

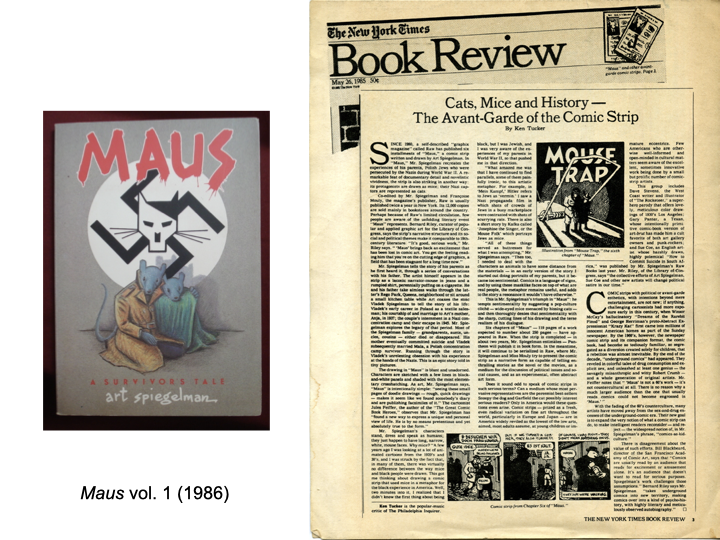

What’s interesting to me is that City of Glass and the first volume of Maus really came out fairly close to each other, and they were both these liminal books that were blurring boundaries, and I think they got tagged with a lot of labels like “postmodern” or “deconstructionist” at the time. Was that something that you felt was being impressed upon your work?

Auster: Yes. First, the detective connection always puzzled me. I mean, obviously, I was using it, but trying to get somewhere else with it. And then, the idea that I was influenced by French theory, and was actually getting all my ideas from Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, it just wasn’t true. And so-- there have been whole books written about this—many books!—about my postmodernist credentials, and I haven’t read these people. [Laughter] I’ve read a lot of philosophy, and a lot of other things, but not those people.

And Art, you had to deal with people writing things like, “This is not a comic,” or “This is an example of postmodernism,” or whatever. Did you feel like your work was being framed by a cultural moment in some way that wasn’t appropriate to your intentions?

Spiegelman: Well my intentions were to find an audience that wasn’t reading comics, and to make a long comic book that needed a bookmark and needed to be re-read to do it. And then-- the article that appeared in the Times talked about it as an example of postmodernism, and I very frankly not only had not read Lacan, I’d never heard the phrase “postmodern.” So for me it was like, I was interested in modernism. So I was just doing it now, and I guess that means postmodernism.

[Laugher]

Auster: I got labelled, later, as post-postmodernism.

Spiegelman: Me too! We have a lot in common!

[Laughter]

David Mazzucchelli: Wouldn’t that be pre-futurism?

[Laughter]

The other thing is, even though City of Glass gets tagged as some kind of detective novel, I think you both have a real authentic connection to detective fiction. I think the work of Art’s that City of Glass reminds me of the most is "Ace Hole: Midget Detective".

Spiegelman: Oh, that’s interesting.

Which is a kind of, I suppose, deconstructionist detective story, among a lot of other things.

Spiegelman: I wouldn’t have used the word deconstructionist, but I would agree that it was a kind of riff on detective stories.

Is that something that you have shared in your friendship as a common interest? Have you discussed this a lot?

Auster: We’ve talked about film noir. I mean, we like that period of American filmmaking, but I don’t know. We don’t have very serious discussions.

[Laughter]

Speigelman: We talk about smoking.

Auster: Smoking, and what are we gonna have for dinner.

[Laughter]

Spiegelman: I’ll just go back to the film part of this for one second, because this was something I wanted to interject earlier, which is, when I first asked Paul about the adaptation of the book rather than making a new book, he said, “Yeah, if you can do it, because I think City of Glass keeps getting optioned for movies over and over again and nobody can figure out how to do it.”

Auster: Nobody could write a script.

Spiegelman: And that makes sense. As you’ll see when David and Paul talk.

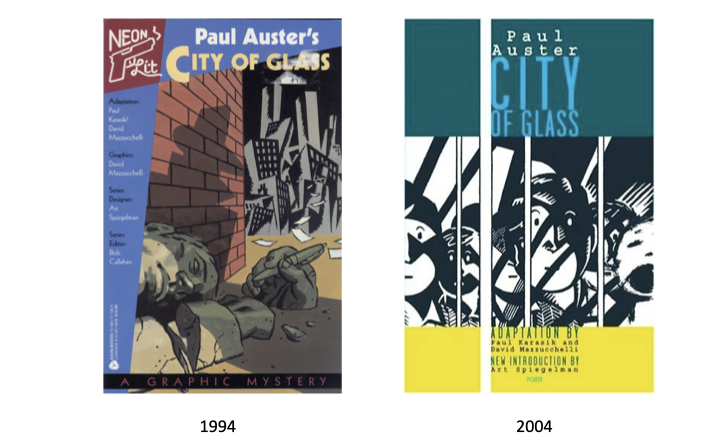

These are the two editions of City of Glass, the original one from 1994 and then the re-edition from 2004. David, you did the cover artwork for both.

Mazzucchelli: We designed it together. I did the cover artwork for the first one, the second one Paul [Karasik] and I designed together.

How does the cover suggest the different contexts for the book over this period of time?

Mazzucchelli: Well, the context really for the first book, [it] was supposed to be the first book of a series. And so Art had designed the graphics, the whole "Neon Lit" dressing - this was supposed to announce this series of books that were gonna be coming out as adaptations of existing contemporary noir. So that dictated a lot about the way that version was supposed to look. And then it just went away for a long time.

Yeah. The book was kind of legendary for a while because it sort of appeared, and then went out of print.

Mazzucchelli: I think we ended up missing the initial release date they wanted, but were told, “That’s fine, we’ll just move it to the next season.” Only to find out that when it was released it was released as a backorder. So the fact that it got 16,000 orders as a backorder is not bad, but there was no follow-up.

Paul Karasik: And simultaneously the editor who was handling the book--

Mazzucchelli: Who bought the series--

Karasik: The one who bought the series, left pretty much the day that the book was released. I spoke once with the person who wrote the review in the New York Times—it miraculously appeared in the New York Times, as just a little blurb—and he said, “Yeah, I got this box from Avon, and there were some cookbooks in it, and some romance novels, and at the bottom was this strange thing that I just dug out.” There was nobody who was promoting this book.

Auster: I didn’t know any of this.

[Laughter]

And Art, how would you describe what the brief for Neon Lit was at the time that it was launched as an imprint?

Spiegelman: I didn’t want to do it. I just didn’t want to do it. I don’t believe in adaptations very much. Although there have been some good ones. And this was a devolution of that original idea of something else I don’t believe in, which is collaboration, which I do more and more of. But I thought that the best graphic novels, comics, were made by single humans. And the idea of marrying novelists to illustrators/cartoon artists of one kind of another seemed possible, but I’d become allergic to it growing up with “inked by,” “colored by,” “penciled by” credits in comic books. And so I was wary of that as a process. [Editor] Bob Callahan, who was desperate for money at all times, said, “We’ll do the adaptations!” I said, “I don’t want to do adaptations.” And he said, “You gotta do it! I can’t pay my rent!” [Laughs] Which, I finally caved and allowed it to happen. And he continued to be unable to pay his rent, so that every foreign edition that came out the artists never saw a penny of, because the money filtered through him and disappeared into his rent for years.

But in doing this thing, we were talking about various possible writers that could work. The only one I agreed with originally was Paul. [First,] because I know how to talk with Paul without feeling self-conscious about letting the various reservations come out as well as my interest, although I think I didn’t know how disinterested Paul was until today. [Laughter] Then we went back to talking about dinner. And then [Neon Lit] got launched because this guy, Bob Mecoy there [at Avon Books] loved the idea, really wanted to do it, and I found this interesting mainly because it couldn’t be done. The thing that I was just talking about with the film adaptations that didn’t work-- [City of Glass] is one of the least visual books I’ve ever been able to read, in that it’s not where it lives. It lives in its sentences. So what to do with that was so absurdly difficult a problem that it became an interesting project. Then, insofar as this series continued, it really devolved. I had to bail and let Callahan screw artists and writers on his own. [Laughter] On the other hand, there were some others that went through. I looked over the second one, and then after that it just disappeared from my mirror and from everybody else’s. The publisher had gone and nobody else wanted to make the books.

Auster: So did the book actually go out of print for a number of years? Is that it?

Mazzuchelli: Yes.

Auster: Yeah.

Mazzucchelli: That’s how we ended up getting the rights.

Auster: I see, I see. Ok.

It was very hard to find. But it was also, within comics circles, highly regarded. I remember I got a copy finally because I visited a friend in Florida who was a comics publisher and also distributed some comics. And he had a box of old distro stuff that was collecting dust and I went through it and there were three pristine copies of City of Glass. And it was like one of those good used bookstore experiences.

Auster: Yeah. So Avon just dropped it. They didn’t care, probably new people were in charge--

Spiegelman: No, they were only impressed that a backorder sold that well.

Auster: So then you got it back and went to Picador, where I was now publishing my fiction in paperback, and you worked with [publisher] Frances Coady. Right?

Mazzucchelli: Yes.

Auster: She just announced it to me. She said, "Well, we’re going to re-do the illustrated version." And I said, great. But I didn’t know any of the-- because you know, we haven’t seen each other in 20 years.

Mazzucchelli: You look good.

[Laughter]

Auster: You do too. Thanks. When I saw you today, I thought, "He looks younger now than he did then..."

[Laughter]

Mazzucchelli: There’s a painting that I have in my attic.

[Laughter]

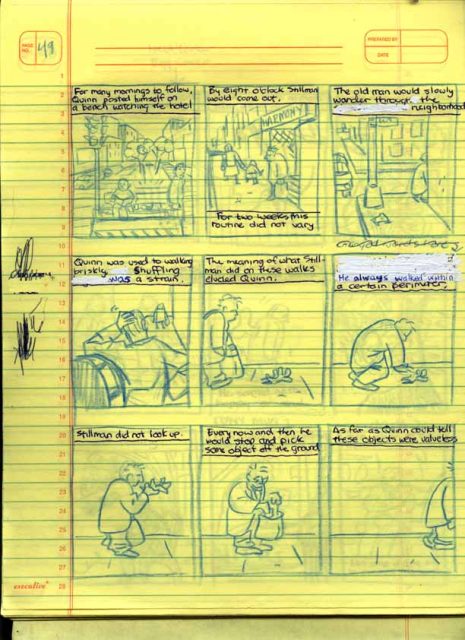

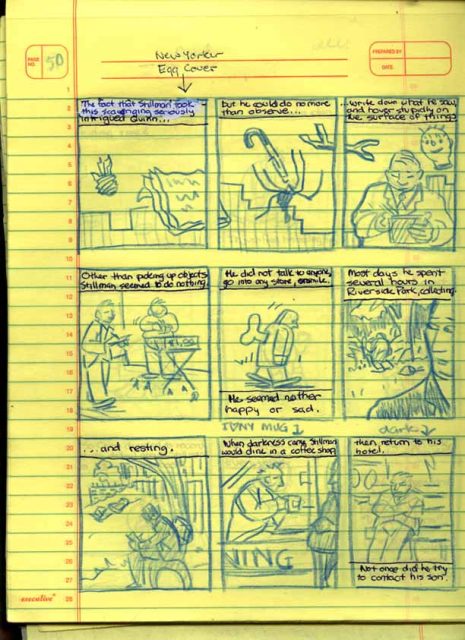

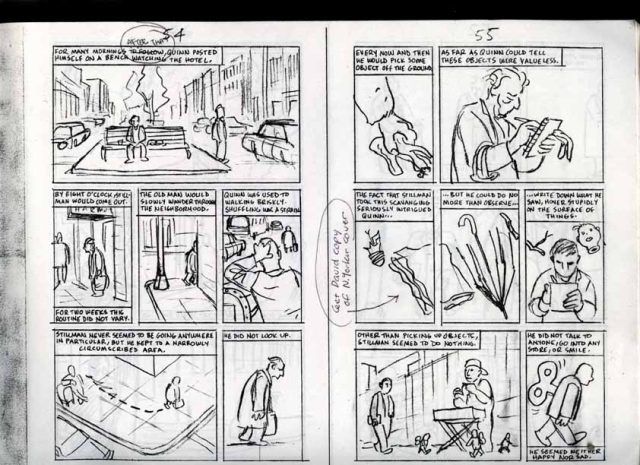

One of the things that came up earlier was the search to find an artist to work on this book. David, you produced some sketches or some drafts before Paul’s involvement in the project.

Mazzucchelli: Yeah, this began for me at a café table in Angoulême, sitting with Art and Art explaining much of what he just explained here about the project, and what it was, and asking if I would like to be involved. And explaining it was a new series adapting crime novels, and I said, “Well, I don’t really read crime novels.” And then he said, "Well, the book that we’re proposing to start with, it doesn’t really fall into that category." So when I read the book I was eager to give it a try much for the same reason that Art thought it would be worth doing. Because it seemed almost impossible. At the same time I was busy with a lot of other stuff I was finishing up. But eventually Art was asking, like, “How’s it going?” And so I had to come up with something that looked like I was thinking about it. [Laughter] And these are some of the pages I came up with. And I think what happened was, I was-- my initial dive into the book, I was looking for a way to tell the story. And what became evident once Paul K. came on board was that that was the wrong way to go about it. That it was really more about finding a way to get into the structure of it. So because I was the first person Art asked, he was stuck with me, so I had to stay on board. But fortunately, you were talking to Paul [Karasik] and Paul had given this some thought several years ago.

You know, I just want to say that for this panel I think it’s really appropriate that there’s a doubling of Pauls. But for the purpose of clarity, I think I’m going to refer to Paul Auster as Paul A., and Paul Karasik as “Sluggo.”

[Laughter]

Yeah, it’s a really seamless, kind of mysterious collaboration. And here we can see your initial draft of the page, and then what came out of it after that collaboration.

Mazzucchelli: Right. I think it’s good to hand it over to Sluggo now to talk about how he got involved.

Karasik: Well this whole story is like a Paul Auster novel on some level. It’s very strange how this all came about. For me, I was living in Brooklyn, and I was teaching at a prep school in Brooklyn Heights. And this was, like, 1979, 1980 or something. And Paul Auster’s son Daniel was in one of my classes.

Auster: He was born in '77.

Karasik: So maybe it was later. That’s right, it was late '80s, he was about 10 years old.

Auster: Yeah.

Karasik: Thanks very much for the clarity. And he was a really interesting kid, drew very funny comics, I just enjoyed him a lot. And I knew his father was coming in for a parent-teacher conference. And this was when all three of the volumes of The New York Trilogy were out. And I thought, wow, this Brooklyn author’s coming to speak about his son. I’d better read his books so that I can brown-nose him, maybe he’ll sign my copy or something. [Laughter] I admired the books greatly, and thought, wow, this is really cool, finally a parent who’s coming who's not a Wall Street banker, I might actually be able to talk to him. So I read the books, and I was really struck at the time by that New York Trilogy. And I had my sketchbook there and I made some little sketches, just kind of randomly thinking about how this might turn into a really cool graphic novel or comic or whatever. I was just making some sketches in my blue notebook. And discarded, never thought of again. Actually, when Paul came to the parent-teacher conference, we never talked about it. We talked about Daniel because we were so charmed and amused by Paul’s son. And then, I don’t know, 15 years go by or something. Time goes by. And I’d moved out of Brooklyn and I get a call from Art--

Speigelman: In the intervening years Paul had taken a sabbatical from being a teacher and became a student at SVA to take the comics classes that I was teaching there. And we got along very well, and then Paul helped on RAW for a while, and somewhere well after that...

Karasik: Yeah, and I’m living in the country and I get a call from Art, and we’re just shooting the shit as we do from time to time, and he says, “You know, we’re starting this series of adaptations of contemporary noir novels into graphic novels, but we’re kind of struggling with this first one that we’re trying to do, and David Mazzucchelli’s on board, but I don’t know, maybe it’s not going to work, it’s kind of an impossible novel to adapt.” And I’m getting more and more interested, and I say, “Well, what’s the name of the novel?” And he said, “Well, I don’t know, you may have heard of it or not heard of it, it’s Paul Auster’s City of Glass,” and I said, “Well, I’ve already started it.”

[Laughter]

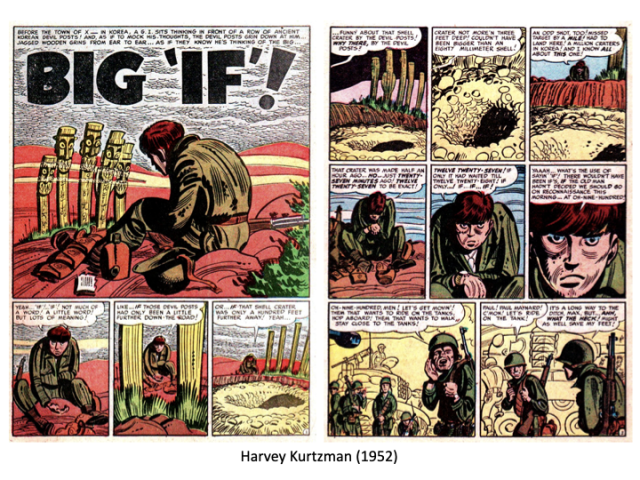

When I work with students talking about this book, one of the things it’s a great conversation starter about is structure. There’s a number of superficial differences between these two versions, but the real key difference is the structure. Which is not to say that would necessarily be immediately apparent just comparing those two pages, but within the context of the book, that structure that underlies the right hand page from the finished edition is really part of this entire fractal-like structure that undergirds the whole enterprise. You’ve talked a little bit in the past about how Harvey Kurtzman’s work has been influential to you and influenced in part your approach to this book. Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

Karasik: Well, you know, this City of Glass is a collaboration on so many different levels. I feel that I learned a lot from looking at the work of Harvey Kurtzman, and his pacing in particular. But, like I said, it’s a little bit like a Paul Auster novel. This book wouldn’t have happened if this strange coincidence hadn’t occurred years before - I hadn’t met Paul, I hadn’t read the book, I hadn’t taken Art’s class. I mean, I was familiar with Kurtzman, but Art Spiegelman is many things, a fantastic cartoonist and illustrator and etc., but for me Art was pivotal as a teacher. He’s a great teacher, and I learned a lot taking his classes on the history of comics, and especially a hard look at Harvey Kurtzman… The structure here [see "Big 'If'!" example above], the page on the right, the three-tiered triptych with a hidden grid that can be broken into three or four permutations, and the quantity of material that can be delivered on a certain page of comics, I feel that Kurtzman is hitting the right balance here.

And the three-panel grid-- so this three-panel grid, loosely, one of the main plot elements of City of Glass is that the main character loses his sense of identity, in the process of which he loses his grip on reality. So this nine-panel grid that you see at the beginning of the book, you’re kind of beaten over the head with it page after page, and as the story goes on the nine-panel grid itself-- it’s actually, the nine-panel grid is hidden in several places in the book; not only the grid itself, but like this tic-tac-toe board, there in the middle of the page, there’s the window behind the guide. So it’s not just the grid, it’s within the the context of the story itself, so that it becomes a visual metaphor for the character’s sanity.

It’s amazing too how it’s sort of this icon that’s embedded in a lot of the panels, and then there are a few examples like this where the whole page itself becomes an icon also. So it’s really operating on the microscopic scale of the panel, the macroscopic scale of the page--

Karasik: And eventually the panels, as his sanity drifts from his mind, the panels themselves start to break apart, the grid breaks apart, and his grip on reality breaks apart and the panels themselves start dripping off the page.

Spiegelman: Could I interject something about the grid? Because one of the reasons this collaboration worked so well is yet another accident that became fortuitous, which is - Paul, although a very good student, totally screwed up when he first did this. He did it on a four-row grid rather than a three-row grid, thinking that it was a bigger format than it was. And the intelligence and the thinking was all present there, but it was all wrong! It couldn’t be done. Not because it couldn’t be done period, which is built into the project, but because it would be unreadable. And that meant that David, who is also a very intelligent cartoon thinker, had to rethink the four-panel grid to start thinking about what it would be on a three-panel grid with you, and that allowed you to enter in as something other than an illustrator of somebody else’s text. And that really made the book lift off from where it was already, now, “We’re gettin’ there, we’re gettin’ there - we’re there! Now we’re there.”

Mazzucchelli: You must have alerted Paul to the four-tier thing earlier, because by the time I got--

Spiegelman: You got a three-tier--

Mazzucchelli: It was a three-by-three--

Spiegelman: Man, but it really made a big difference to change it down and around that way, it tightened it up into a stratospherically successful--

Mazzucchelli: And what happened was, was that Paul, because he had such a handle on getting into the structure of the book-- [Karasik] worked up an entire draft with sketches for the whole book. With this nine-panel grid. Which was our starting point, really. And I think, if I remember correctly, the first thing that you worked on was that strange monologue of Peter Stillman the younger.

Karasik: Yeah. Chapter two of the book is devoted to a 20-page monologue or soliloquy by this poor young character who has been locked in a closet by his father. And that was a real challenge. Because, how do you turn a monologue into something that is going to be visually interesting to the reader? And keep all of Paul’s words, condense it, and give it some sort of visual richness? And once that problem got solved, everything else was smooth sailing.

What’s really interesting about this is that because the grid is such a constant presence, it allows you to have these non-diegetic sort of panel transitions, where the images don’t even necessarily have a very obvious reference to one another, and yet because you’re sort of locked in this rhythm in the book you accept it, and the text pushes you forward as well.

Karasik: So this sequence here, it starts out-- it’s, I don’t know, 12 pages long, down from 20 in [the novel], something like that. And you can see in this spread, it’s about halfway through it, and if you see the upper left hand corner there, they’re couplets-- the two panels with the well, two panels with the bird, two panels with the comic strip, two panels with the dog shit, and then you get to this page and it’s one panel per bit of dialogue. So that we’re increasing the velocity of this character’s frantic speech page by page, until finally we end up down at the bottom of the well with him. So we’re let inside of this poor tortured man’s psyche, and we have to find a visual way of doing that, of actually getting inside of him.

And quite successfully. I think, to go back to the legal paper draft that you were talking about before, this is something that came all from you, right Paul? And then this is a version that was returned by David.

Karasik: Yeah. So this is a great example. I handed the yellow pad sketch to David. And then David did his version of the sketch. And I wanted to point out one of the really important changes. You know, which is the first panel on the upper left hand side. That nine-panel grid and all those little sketches I was doing just got so claustrophobic that the book was missing an important aspect that Paul Auster had in there, which was New York City as a character. And David brought some air back into this. After years of drawing Daredevil he knew how to draw an urban landscape. [Laughter] He really can draw an urban landscape like nobody’s business. And so suddenly, the huge transformation between my pitch and David’s pitch, the city is a character and the atmosphere, the air.

Mazzucchelli: I remember when we got your version, I think every page had a nine-panel grid, except for one or two full pages, and the structure was terrific. But in parts it became less easily readible, a little claustrophobic, and there were places where obviously you had gotten the rhythm of it just right, and other places where it seemed like even you were struggling a bit, like, “Well, I’ve got to work within these panels, but how am I going to find the right images?” And that was where, after talking about it, opening it up like this allowed it to be more readable. And since I had done a few years of commercial hackwork, I was familiar with how to make things more accessible to the public.

Karasik: God bless you, David.

[Laughter]

But you were also contributing visual ideas also…. On top of restructuring the book - contributing a sense of atmosphere, contributing visual ideas; of course, there’s just beautiful ink and brush drawing here too, that gives it a really appealing surface.

Karasik: You know, one teeny little revelation here. This issue of the New Yorker [second tier, pg. 57]-- I was doing the adaptation of the book, and this issue of the New Yorker was in my bathroom, it’s an actual cover of the issue of the New Yorker. And it’s got a Humpty Dumpty falling, which is an obsession of one of the characters of the book, this character Humpty Dumpty-- and this sounds so much like you wrote this Paul, on top of that, inside is a story about Kaspar Hauser, the wild child--

Auster: Oh right! Who’s referred to in the novel! Boy. See how strange the world is!

[Laughter]

Karasik: It had to be in there.

One of the features of the book is that not only is the structure manipulated throughout, but the style shifts a lot too. Even within the book, there’s a number of different visual styles, David, that you use. Some are more iconographic, some are specific references, like to a woodcut visual style. But there’s a kind of core visual style that’s the neutral style of the books. How are you thinking about what that “neutral” style needed to be in order to accommodate the various shiftings that this book required?

Mazzucchelli: Well, the first thing was, the book was this big. So I knew that I had to draw in a style that would read at a small scale, which is why I went to something as relatively simple as it was. And there were certain things that were in Paul’s version-- [Karasik's] was really rough, it didn’t really deal with style so much, but you had already sort of established that Quinn was going to be sort of a relatively blank, egg-like character—the egg, sort of, shaped head—and once you do something that cartoony, you can’t let the rest of the drawing go too realistic, or it’s a little too jarring. So it had to exist in this halfway between cartoon and naturalism. And then, since there were so many parts of it that diverged from the main line of action. That, I think, was the first place I got really interested in adapting the way I was drawing to demarcate: now we’re inside this character’s head talking about this, or now we’re in the past, or now we’re talking about this particular moment. And so that was a way for me to allow that layer in addition to all of the things we’re talking about: the language, and the structure, and the drawing - let the style of the drawing be another indicator of where we’re moving, and not let it ever let it get so far away that it felt like we’re in another book. But that it was still connected.

You had referred to some of the work that you had done as a younger artist as “hackwork.” It’s still work that’s greatly admired by a lot of people today… Art had identified that you had an ability to draw these kinds of urban, noir--

Mazzucchelli: I think this is the only superhero comic you’d looked at in like, decades or something, right?

Spiegelman: I’d looked at some of the Daredevils, also. There was a time when one could keep up with everything because nothing was happening. [Laughter] So at that point, you really rose to attention quickly as something to look at, because whatever it was, it didn’t look like the Wayne Boring version. Which I like also.

Mazzucchelli: Oh, I like Wayne Boring.

Spiegelman: But happily, it did not look like whoever it was that was doing Daredevil before that. Was that Gene Colan? Or something like that, which was really just illustrating and not thinking about what became really obvious in City of Glass, which is the anatomy of comics rather than the anatomy of muscles.

Mazzucchelli: Right.

Around the time that you were doing City of Glass you were also self-publishing a comics anthology called Rubber Blanket. And this was a very experimental period for you. And you were working in a lot of different idioms, a lot of different visual styles, the visual style is moving a lot more towards a kind of cartoony abstraction. Did working on City of Glass-- was that an extension of your interest at the time, or did it fold back into the stuff you did afterwards?

Mazzucchelli: It was a good project for me at that time. My thinking was already going in that direction. I was publishing my own comics, and trying to push my own writing, my own way of dealing with storytelling, graphics, and all of the visual aspects of how comics work. And then to have this project, which really stretched the way I think both of us thought about what comics can do and how to take complex, non-visual information and find these visual analogs for it, it happened to be a really good project for me at the time as far as what I was doing and continued doing.

Since we have Art here with a fiction writer, I wanted to bring up an incendiary quotation from another piece of work by Art, that also has a kind of film noir inflection. In the last two panels of this sequence, you’re talking about fiction and the possibilities of fiction, and you say that fiction was invented so your spouse wouldn’t kill you, but fiction always struck you as playing tennis without a net. Whereas Paul, you’ve done a combination of memoir, and fiction writing and working in other idioms. Have you ever been tempted to write a fictional work?

Spiegelman: Constantly tempted. And I just keep trying to find the net. Like, I find that when one tries to say something true, in the sense of something that happened rather than something emotionally true, I just find, like: took place in a hotel in Chicago, no, no, no, a motel in Indiana, no, uh, my apartment. And the possible shifting ground rules, I keep trying to find what the motor was for making the fiction, which gets me back to something I directly experienced, then I lose track of the fictional structures. So I find myself constantly reading books on, like, how to write fiction. But one of the times that Paul and I had a semi-serious conversation, I was whining about exactly this issue. And the thing that was amusing to me-- I was trying yet again to figure out the solution of how to write a fiction story, based on a manual on how to write fiction, actually. A weird object on how to write fiction called the “Plot Genie” from the 1920s, where you would spin for your characters, and location, and complication, and I was working from that and working out a story. But what was really fantastic, is I’m whining to Paul. Paul then says, “But Art, just think of it, weren’t you ever a kid?” I said, “I think so, I can’t remember.” But then he says, “But you take these like little teddy bears, and stuffed dolls, and toy soldiers, and go, ‘Oh yeah?’ ‘Yeah!’ and it’s just like, it’s a puppet show, man, just, like, let it happen!” But the only thing that stuck with me was the character I’d spun for for the female lead was a ventriloquist’s daughter. At which point I did a sequence about Paul telling me to think of it as a puppet show. [Laughter] This is still a half-formed strip that I will return to.

[Addressing Auster] Have you ever used the Plot Genie?

Auster: I never knew about it until Art told me. It sounds like, let’s see, Dada Manifesto #7, Tristan Tzara, who said, do you want to write a poem? Take a newspaper, cut up all the words, throw them into a hat, and pull them out one by one, and just write down, in order, the words. And there you are, a poet and a genius.

Spiegelman: Ok, I’m gonna make a hard copy on paper. I can’t cut my iPad up.

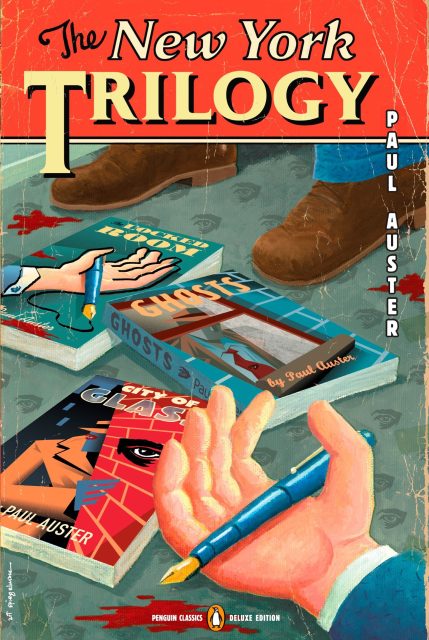

One other image I wanted to make sure that we looked at that spins off of this whole discussion of City of Glass and collaboration and everything: Art, you had designed a new cover to a relatively recent deluxe edition of the New York Trilogy--

Auster: It’s the “Penguin Classic,” you see. [Laughter] All these years go by, and the book that was rejected, nobody wanted, and now it’s a Penguin Classic. A beautiful, illustrated series, one of several done by comics artists. So it was only appropriate that Art should do this. I know that he knocked his head against the wall, he spent much more time on it than he should of. Because he not only did the cover, but he did the flaps, he did the back, and then he did frontispieces for each of the three within the book. It was quite a lot of work. So it was another one of my very happy collaborations with Art.

Spiegelman: That worked out really well. But the thing that took me the most time was learning how to make a distressed, pulp-looking cover on Photoshop. Really, a month was lost there.

[Laughter]

You were very involved with one very intense collaborative process of visualizing this book once. Was there any anxiety about repeating those earlier solutions?

Spiegelman: Oh, no, I was grateful that I had a place to start thinking from. Part of that little parade of City of Glass covers that you showed, you didn’t show some of the more modern, very graphic design-y solutions to new editions of [Auster's] work… there’s different ways of attacking it. I found that the pulp roots that are somewhere embedded in this “postmodern novel that looks to Derrida” were worth bringing back to the fore.

Auster: “Soi-disant!”

[Laughter]

This is a sketch for the complete version.

Speigelman: I knew it had to have a mapback, because when you were showing the Maus thing before, that was what attracted me to the old Dell paperbacks. And it’s definitely a concern of Paul’s; clearly place is an important part of every one of the books I’ve read of Paul’s, and the map, the aspect of the map was important, and like the back cover of Maus, I felt that something that could be a map with an inset Tower of Babel-- that was an early part of finding a solution to what I was doing.

[Q+A from the audience commences]

The post <em>City of Glass</em>: It Was a Phone Call That Started It appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment