The work of John Romita spanned several eras, and defined one. He was among the first generation of comic book readers to become comic book professionals, and the bright, romantic realism of his style spoke of youth and idealism. His death, peaceful in his sleep, was announced last Tuesday by his son, the formidable cartoonist John Romita Jr. Despite having one of the longest and most storied careers in the comics business, packed with major accomplishments, Romita will probably be forever associated with The Amazing Spider-Man, a title on which he succeeded and soon exceeded the run of original artist Steve Ditko. He later served as art director at Marvel Comics, contributing to the designs of popular characters like Wolverine, Luke Cage and the Punisher.

John Romita was born in Brooklyn, NY, on January 24, 1930, to parents Marie and Victor Romita. He was one of five children. The young Romita was an avid reader of comics; he would spend hours poring over Milton Caniff's Terry and the Pirates, and delighted in the early work of Jack Kirby. As a young teenager, Romita attended Manhattan’s School of Industrial Art: "They were all excellent, excellent teachers and wonderful role models," he said to Tom Spurgeon in a 2003 interview, "because they were all practicing, earning artists." He graduated in 1947, and was soon working professionally in the commercial sphere, holding down a full-time job at a company named Forbes Lithograph for a measly $25-$30 a week. However, a chance encounter with an old classmate, Lester Zakarin, changed Romita’s fortunes. Zakarin was working in the comic book business, and offered his friend around $20 a page to ghost-pencil a 10-page story for him. Romita immediately realized that he could make far more money as a cartoonist.

Romita tentatively entered comics in 1949 with an assignment for the seminal Eastern Color title Famous Funnies. His lack of experience was obvious on this initial assignment, a romance tale, as he ruefully recalled years later in an interview with fellow cartoonist Jim Keefe and John Mietus: “It was terrible. All the women looked like emaciated men.” Although Romita was paid $200 for his work, it was never published, "and rightfully so." Romita’s ghosting for Zakarin, however, brought him to houses like Timely, the precursor to Marvel Comics. He eventually earned a co-byline, signing some of his pages “Zakarin Romita.”

Romita was drafted into the Army in 1951. Shrewdly, he showed some art samples around on Governors Island prior to his induction, and was assigned work on recruitment posters shortly after basic training. In his off-duty hours, he journeyed into Manhattan in search of freelance art jobs. Sometime in late 1951, Romita dropped by the Atlas Comics offices in uniform; Atlas was the new name for Timely, where Romita had been ghosting for years. The editor, Stan Lee, assigned him a four-page science fiction story, pencils and inks, and was pleased with the now-solo artist's work. Soon, Romita was getting regular assignments in a wide variety of genres for Atlas, including horror, war, westerns and romance. In 1952, he married Virginia Bruno, his childhood sweetheart; they had two sons, Victor and John Jr.

Soon after, Romita worked on a short-lived, Commie-smashing revival for the Joe Simon/Jack Kirby character Captain America in Young Men #24-28 (Dec. 1953 through July 1954) and Captain America #76-78, May through Sept. 1954). It was his first focused foray into the superhero genre, and its failure stung him. "Stan always told me it had nothing to do with the artwork," Romita told Spurgeon; the political climate was all wrong for Cap's brand of two-fisted patriotism. The next decade would prove better for the Timely superheroes.

Romita might have stayed on with Atlas through its transition to Marvel, but in 1957 the company dropped dozens of freelancers, electing to draw instead on a backlog of already-commissioned stories to fill new issues. Romita himself was unceremoniously terminated mid-assignment via phone call from Lee's secretary, and was not paid for the work he had finished. His options limited, he applied for work at rival publisher DC.

Although romance comics were at one time the most popular genre, accounting for one in every four comic books sold, the craze eventually faded. By 1965, Romita’s romance work for DC had dried up, and no offers from DC's other departments were forthcoming. He migrated back to Stan Lee, who'd been trying to lure him away for several years. The Marvel superhero line was hot, and Romita's first assignment saw him reunited with Captain America, inking a Jack Kirby cover and Don Heck interior pages on The Avengers #23. At the same time, Romita began to explore a $250-a-week job at the BBDO ad agency. He decided that if he did take on any comics assignments, he’d concentrate on inking, which was much less stressful and time-consuming than creating penciled pages.

When Ditko left The Amazing Spider-Man after issue #38 (July 1966), Lee had Romita lined up as his immediate replacement for issue #39, initially inked by veteran Mike Esposito (who used the pseudonym "Mickey Demeo" because he was moonlighting while under contract with DC). For a while, Romita thought he might return to Daredevil when everything was patched up with Ditko. "After about a year," Romita told Spurgeon, "I realized he wasn’t coming back." The Romita-Esposito team continued through issue #66 (Nov. 1968), with Romita himself inking a handful of issues during that run, and Jim Mooney contributing a single inking job.

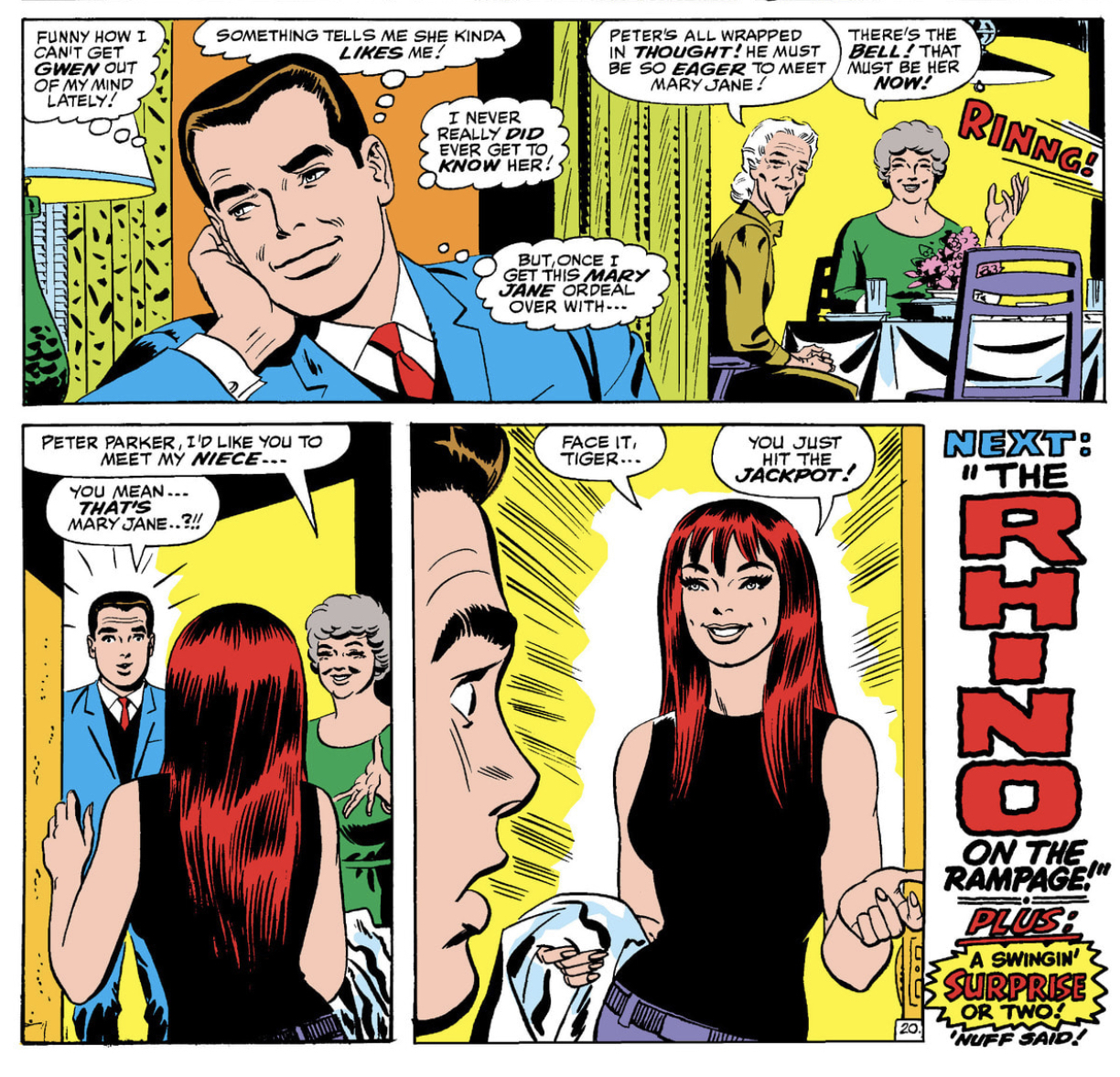

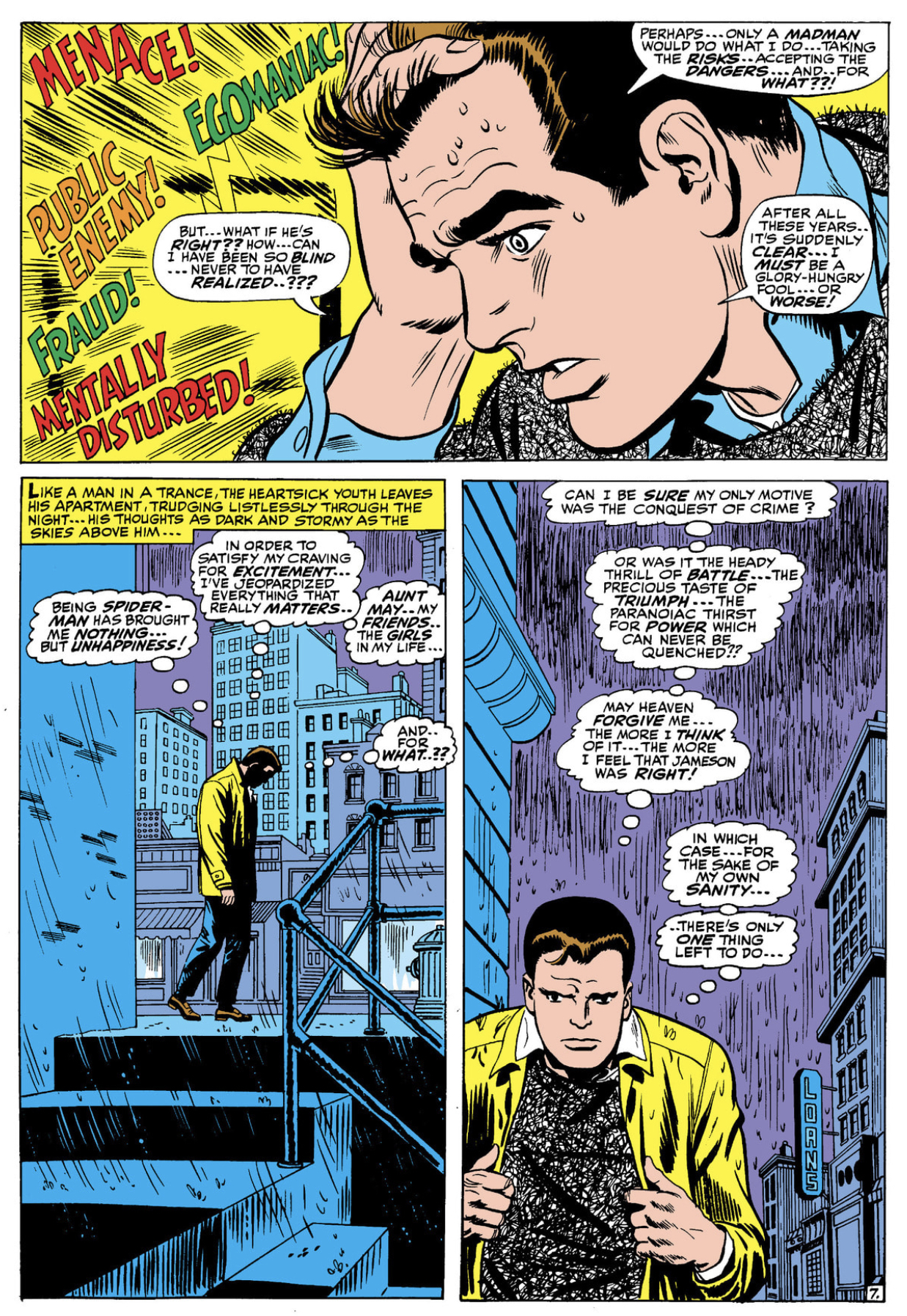

Romita’s fears about following the popular and innovative Ditko proved unfounded. A year after his taking on the title, he was informed by Lee that Amazing had eclipsed Jack Kirby's Fantastic Four as Marvel’s flagship title. Romita’s long experience as a romance comics artist injected a welcome note of sex appeal into the Spider-Man cast, particularly in the form of Mary Jane Watson: a gorgeous, confident redhead who would become Peter Parker’s main romantic interest for much of the franchise's history. Mary Jane, in a sense, pre-dated Romita; she had been referred to without being seen since issue #15, and made a brief, visually-obscured appearance in issue #25, during Ditko’s tenure, but Marvel readers got their first real look at her on the famous closing page to Amazing Spider-Man #42 (November 1966). The character typified Romita’s skill at rendering beautiful and fashionable people, adding an extra element of reader interest to the already-popular title.

At the same time as he was shepherding Spider-Man to new heights of esteem, the versatile Romita was increasingly asked to work on corrections and changes to other artists’ work in order to maintain the Marvel house style. "I had an unofficial title," Romita remarked to Jon B. Cooke in 1999. "[Stan] told everybody I was the Art Director." This was not a paid position, but the added demands took their toll on Romita’s drawing schedule; from February 1968 to August 1969, the artist only did layouts on his signature title, with Jim Mooney handling the finished art. Romita then withdrew to only the covers for six issues (#76-81), with John Buscema stepping in to do interior layouts for other artists to finish. Romita finally ended his run as penciler on Amazing with issue #95 (April 1971). In addition to his work on the regular title, he also did interior work on The Amazing Spider-Man Annual #3 (1966) and both issues of The Spectacular Spider-Man (July 1968 & Nov. 1968), an abortive attempt to break the character into the b&w newsstand magazine market.

After Lee was promoted to publisher in 1972, Roy Thomas became editor-in-chief, and Romita's duties as the company's art director became formalized and more critical. He subsequently had a hand in designing the overall look of Marvel's titles, ensuring consistent likenesses among all the characters and helping design new ones. These were skills he had honed building distinctive designs from Lee's minimal plot instructions - sometimes just a few words, like Kingpin of Crime. "The silhouette was what I was after," Romita remarked to Spurgeon. "You can see a silhouette of the Kingpin and you don’t mistake him for any other character. All the other gang leaders in comics, if you put a silhouette up, they’d all look alike. That’s what I was after, a distinctive quality."

In January of 1977, Romita reunited with Stan Lee to launch The Amazing Spider-Man newspaper strip, the realization of a dream the two had cultivated since 1970. It was a bold move in an era of declining readership for adventure strips. Though it started slowly, the strip grew in popularity, and endured until 2019. However, Romita was long gone by then; he felt constrained by the rigid format and crushing deadlines of the comic strip format, and left in 1981 to resume his art director duties at Marvel. By this time, Jim Shooter was the editor-in-chief; under his watch, Romita implemented an apprenticeship program, by which dozens of young artists entered the industry. But times were changing. He was unhappy to be caught up in the controversy surrounding the return of Jack Kirby's artwork. The new style of superhero comics predominant at Marvel as the '80s became the '90s did not appeal to him. Marvel came into the possession of investment tycoon Ronald Perelman, and underwent a rapid and disastrous expansion. "[T]hey were not building it for us," Romita lamented to Spurgeon, "they were building it for themselves." As the company careened toward bankruptcy, the office culture became intolerable; he quit in 1996.

But his place in history was secure. He was inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame in 2002. His work appeared on postage stamps, on the cover of TV Guide when the movies started up. He kept drawing, at his own pace. When an anniversary issued needed something special; when Spider-Man needed that crucial link to the past; when readers wanted to remember those jazzy years of the Marvel age - John Romita was there.

The post John Romita, 1930-2023 appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment