I.

Everybody likes a seedy Hollywood story. Gritty sex. Tarnished glamour. Strangled dreams. But walking a graphic novel down mean streets already occupied by The Little Sister, Play It as It Lays, and Ed Wood is like the new kid calling “Winners” on a playground’s courts. Sammy Harkham struts Blood of the Virgin out with swagger, style, and a chip on his shoulder.

It is 1971. Seymour1 (no apparent last name), Virgin’s central character, is 27 years old. He was born in Iraq (like Harkham's father), but because it expelled Jews in the early ‘50s, grew up “mostly” in Australia (like Harkham's father, and, to an extent, Harkham himself). He has been married for three years to Ida, a daughter of Holocaust survivors, who was born and raised in New Zealand. (How they met and when they came to America is not addressed.) If Ida had a career outside of “housewife” I did not catch it. If she is aware of feminism or consciousness-raising groups, it is not apparent.2

Seymour and Ida have a son they call Junior, so I presume his name is “Seymour” too, though Jews don’t commonly name a child for a living relative. His age is unspecified, but he's less than a year old; he has not given up breast-feeding. Seymour and Ida squabble over child care, grocery shopping, burnt-out light bulbs, ceiling mold, a balky car, whose turn it is to use it - and sex. “Your marriage won’t last,” Seymour is told early on.

If Seymour’s domestic road is rocky, his professional one rides no smoother. He wants to direct movies but is stuck editing trailers for Reverie, a Poverty Row studio. A Clockwork Orange, The Last Picture Show, The French Connection, Carnal Knowledge, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, and Two-Lane Blacktop issued in 1971, but no one in Seymour’s neighborhood seems to know it.

Seymour has been at Reverie for "[a] couple years." Its head, Val Henry, came to Hollywood in 1946 from England, hoping to make Ginger Rogers musicals. Now he churns out flicks for “yokels” and “bumpkins” to consume at drive-ins and grindhouses. Biker films. LSD films. Horror films. For Val, the point is grab-the-money. The point is starlets in your pool.3

Seymour is circulating a script he has in progress. When Val offers him $5,000 for it, he reluctantly accepts, though Val won’t let him direct. The film is to be called "Blood of the Virgin" because a poster flashing that title has already drawn financing from some–in Val’s terms–“slobbering idiots.” Since these idiots expect the cast to include a has-been once-name actor, Seymour must work in footage shot a year earlier of him running around a burning building, even though he won’t accept Val’s calls and is unavailable for additional scenes.

The making of this film will occupy most of the book’s narrative.

II.

Along the way, some “normal” or “expected” Hollywood fare occurs–meetings at the Polo Lounge, parties with cocaine and kinky sex–and some that is unusual (and, more or less, edifying), like step-by-step directions for making a head mold.

There are many distinctively drawn and efficiently personalized characters. Among the most notable are: Joy, the female lead–and (apparent)4 occasional lover of Seymour–who is just back from filming "Cobrawomen" and "Jungle Bitches" in the Philippines (Joy hates movies and thinks them “corny”); Perce, the male lead, vain, nasty, and a past beau of Joy’s (bitterness, on both sides, lingers); Oswald, the hippie director, who is younger–and artier–than Seymour, making him an object for Seymour's disdain and resentment; Terry, installed by Val as producer, to ensure shooting proceeds on schedule and on budget; Myrna, an assistant to Seymour, who is plump, sad, and has a husband in Vietnam (she and Seymour will end up in bed together); and Verna, who, cast as an old hag, upon meeting Seymour asks, “You eat pussy, honey?”5

The film is beset by indignities. Grip trucks arrive at the wrong location. Actors don’t show up, forcing someone else to step into their role, re-written to meet that person’s appearance. Actions are limited so actors don’t damage their costumes. Script pages are eliminated–and locations cut–to keep to schedule. Shooting is stopped before the production concludes because the financiers have pulled funding. The edited reels are taken from Seymour before he can request reshoots - and he is not invited to the wrap party.

Such events shape the philosophical views on display: L.A. is “the dustiest shithole in the world” (Seymour); “[L]ife is a joke” (Terry); “Even at its best, life is... annoying” (Ida).

No alternative is presented.

It is a grubby tale, relayed through a stripped-down aesthetic - but with episodic luster.

Seymour delivers bad news to Oswald in a finely-calibrated four pages of dialogue, facial expression, and action. There are several moody, well-paced silent drives down dark streets. Seymour takes a resistant Ida to a family party in which relationships and antagonisms–Sephardic Jew vs. Ashkenazic; Iraqi vs. Zionist; Baghdad vs. L.A.–are on eye-opening display. And credit must be awarded the two-page spread which opens the book. On a giant screen, in an old-fashioned movie palace, before a dozen dozing, snacking, smooching customers, a naked, BAZOOM-busted, blood-spattered woman with a face stripped of flesh to the bone, confronts an attacker with a knife.

Oh, the horror, the horror.

The humor, the humor.

III.

The story is interrupted by two flashbacks.

The first begins in 1915 in Coconino, Arizona and ends in Hollywood - apparently not too long before we meet Seymour. It tells the story of Joe Clayton, who begins as a ranch hand and ends up an Oscar-winning movie star, bitter and alone, nursing old grievances and appropriating Sam Goldwyn’s line about the crowd at Louis B. Mayer’s funeral–“They wanted to make sure he was dead”–to explain his attendance at that of the producer Bert Cole, his personal bête noire. I suppose this section provides a history of Hollywood; a grounding for Seymour’s story; an affirmation of the maxim “The more things change...”; but...

What interests me the most about it is its anti-Semitic undercurrent, most clearly expressed when Bert, Joe, and a young woman sail to Catalina and encounter a hotel posted “No Negroes No Movies No Jews” to which Bert quips, “Ridiculous - negroes don’t go to Catalina!” Later, when a Baron von Koenig, whose presence is never fully explained, attempts to involve Joe in a movie in Eastern Europe, Bert counsels, “Forget the Baron - I wouldn’t trust him over a dozen Jews” - and then goes abroad to do business with him. By this point it's the 1930s, when Hollywood’s (mostly Jewish) studio heads were tailoring films to avoid offending the Nazis and losing the German market. While Bert’s indifference to the hotel sign and back-handed “compliment” to Jewish honesty seem to mark him fairly clearly, nothing about the Baron or his politics is made explicit, so I am left wondering about his–and even Harkham’s–attitude.

And speaking of anti-Semitism, the second digression begins in Budapest in 1942 and is told entirely–and dramatically–in wordless panels. It concerns an unnamed Jewish mother and daughter who are taken to a concentration camp. The mother escapes and, in the episode’s last panel, is in a deck chair aboard a ship, leaving Hungary.

On the next page, with the main story resumed, the very first panel depicts a woman in her living room, in the same posture as the woman in the deck chair. Ida and Junior are visiting her family in New Zealand; this is her mother. Much happens on this visit, but while I am on the topic, let me call attention only to the Holocaust jokes Ida swaps with a Gentile boyfriend.

IV.

I am about to discuss Blood’s ending.

Perhaps the book’s most striking secondary character is Myron Finkle, whom Seymour meets when at his most despondent. Finkle (apparently) directed (or wrote, or both) horror films Seymour esteems. Now he is bumming cigarettes - and a four-martini lunch. “I can’t,” he says, “get shit to roll down the bowl.” “Whatever I’m selling, showbiz ain’t buying.” He is the ultimate cynical, wised-up insider, full of stories of being paid in bennies, producers with two-faced weasels on their desks, oversold points, seeking a career boost from Barbara Rubin, heroin addiction, rehab in Connecticut, and comparing winning an AFI award to “being the world’s tallest midget - who gives a fuck?”

Finkle is masterfully drawn, with slit eyes, slick-backed hair, and slouch. In a pitch-perfect, three-page, 24-panel near-monologue, he delivers the book’s message. “The tortured artist thing is over.... Ain’t no kike milkman from Steubenville coming out west to be a mogul....6 This industry is all owned by multinational corporations.... Dying on your artistic sword [is pointless].... Settle in and carve out a piece that's fair.”

The evening following this lunch, Seymour and Ida take a walk. They enter a seemingly long-abandoned mansion. (Whose mansion is not identified, but paying attention to window frames and shrubbery gives you a good idea.) As they wander about, Ida tells the parable of the cat and the bell. “The mice are being terrorized by a house cat. They call a meeting to discuss what to do.... Finally one of them [suggests] ‘If we tie a bell around the cat’s neck, we will always know when he is near.’” Then one mouse asks, “‘So, which of us will tie the bell...?’”7

And what is the cat? I ask myself. Hollywood? And who the mice? Artists?

If so, hasn’t Myron Finkle already belled it? Hasn’t he warned Seymour of what is coming - and told him he can do nothing about it but lie back and enjoy it? Which leads to the more interesting question: what sort of “artist” is Seymour?

He seems to aspire to nothing beyond making a better class of horror film. His hero is Val Lewton. (He dismisses Antonioni as a “phony.”) “The only movies that matter” (emp. in original), he declares, are films like I Walked with a Zombie and Bride of Frankenstein. (He does not explain the reasoning behind this judgment.) Even his passion seems intellectually limited. When a fanzine publishes a review he has written, it must change “every word.”

Why does Seymour aspire to so little? Why is his mind so foreclosed from what is generally considered superior cinema? Perhaps one can make great horror films–or horror films that are superior to other horror films–but what causes one to place horror at the core of one’s creative consciousness and not venture beyond it?

My wife Adele, who is psychoanalytically trained and tends to treat characters in books as if they were patients in her office, points out that both Seymour and Ida are children of traumatized parents, his by the Iraqis and hers by the Nazis. How, she wonders, did being raised by such parents affect them? Of what were they deprived? We are left barely informed. Seymour seems estranged from his father. (“I call him every Thursday,” he defensively explains.) He never mentions his mother. When Ida visits her parents, they seem annoyed she is around - and she seems to derive no pleasure from their company. It may be a fair assumption that anyone who endured what Seymour’s and Ida’s parents did will have been traumatized in ways that affected their parenting skills, but it does not seem appropriate to assume these traumas would–without differentiation, without additional information–afford an understanding of these children’s lives three decades later. All similarly unhappy parents will not produce unhappy children who are alike.

The situation is compounded by Harkham’s writing his book without captions. All information comes from dialogue and drawings. This is similar to how movies work in that movies only provide film frames and conversation - unless they have a voice-over. Harkham never utilizes the comic equivalent. If you do not pay close attention, you may not understand what has happened. (Hence all my “apparent”s.) Even if you do, you may not. (If you don’t catch one specific panel, you won’t know the likely fate of the little girl in the concentration camp.) You have to make your own determination based upon what is within you, as if the panels belong to a Rorschach test of narrowed possibilities. Many questions–besides those I’ve already alluded to–are not answered. Who is Ida mad at among Seymour’s family members? Is the motorcycle crash fatal? Why is Rachel (Ida’s sister) so bitter? “Abandonment” alone doesn’t cut it.

Eliminating captions denies Blood an outside narrator to provide information to readers. Flashbacks could, but Harkham’s don’t involve Seymour or Ida directly enough to be of value to this line of inquiry. Harkham has Seymour reflect once–movingly–through thought balloons about the birth of Junior, but never has him look any wider or deeper or further back. Harkham could have had Seymour converse with a friend about his past. He could have lain him on a therapist’s couch. He did none of this, which is his right as an artist; but I think it cost the book, which ostensibly deals with “real” people in a “real” world, significantly. “There is so much more he could have done,” Adele says, “if he’d understood why he didn’t.”

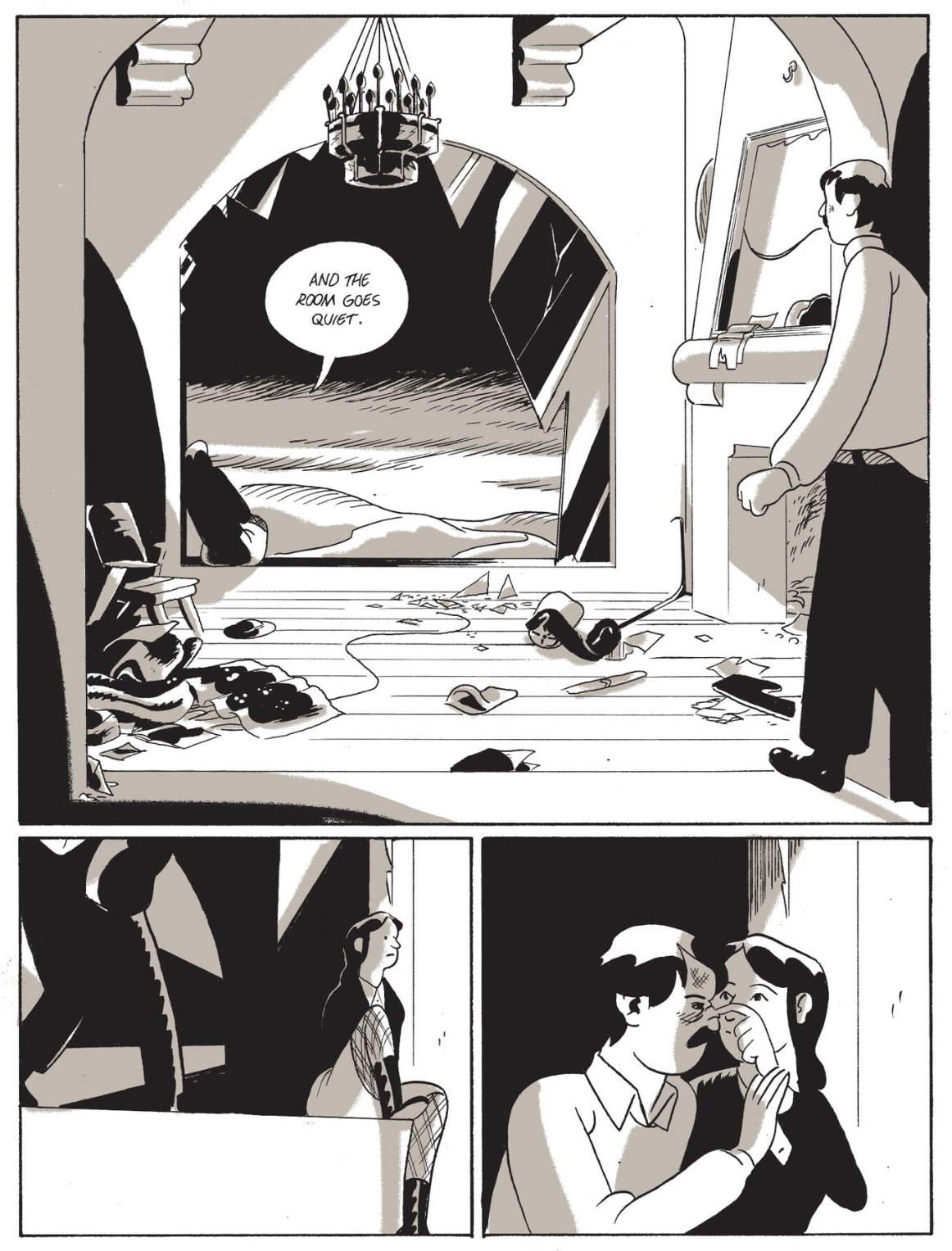

At the end, Seymour and Ida warily kiss.

Hopefulness?

But turn the page and "Blood of the Virgin" is on a theater marquee on a desolate street between "Flesh Grinders" and "The Torture Dungeon".

Futility?

* * *

The post The Big (Blighted) Orange appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment