There’s a certain moment in the Radiohead song “You and Whose Army?” where the brooding atmosphere of the beginning two-thirds is shattered with some resounding piano chords, and the song moves shockingly into a new area. Everyone probably has their own favorite example of this - any work of art that changes direction midway through, or at the end. These changes are fascinating for many reasons, but one is that they open new doors, so that the work we had been experiencing up until then is changed, retrospectively, even as we move forward through it.

This kind of exciting portal-opening is evident in Paul B. Rainey’s Why Don’t You Love Me?, a conceptually adventurous and emotionally moving graphic novel that serves in its first half as a meditation on tedium, depression and modern heartbreak - and then, in a gradual and surprising move, shifts the perspective towards a new genre, providing an exploration of a nuclear apocalyptical mode that is powerful and haunting. It is a remarkable graphic novel, which balances pathos, cruelty, realism and science fiction in an astonishing way.

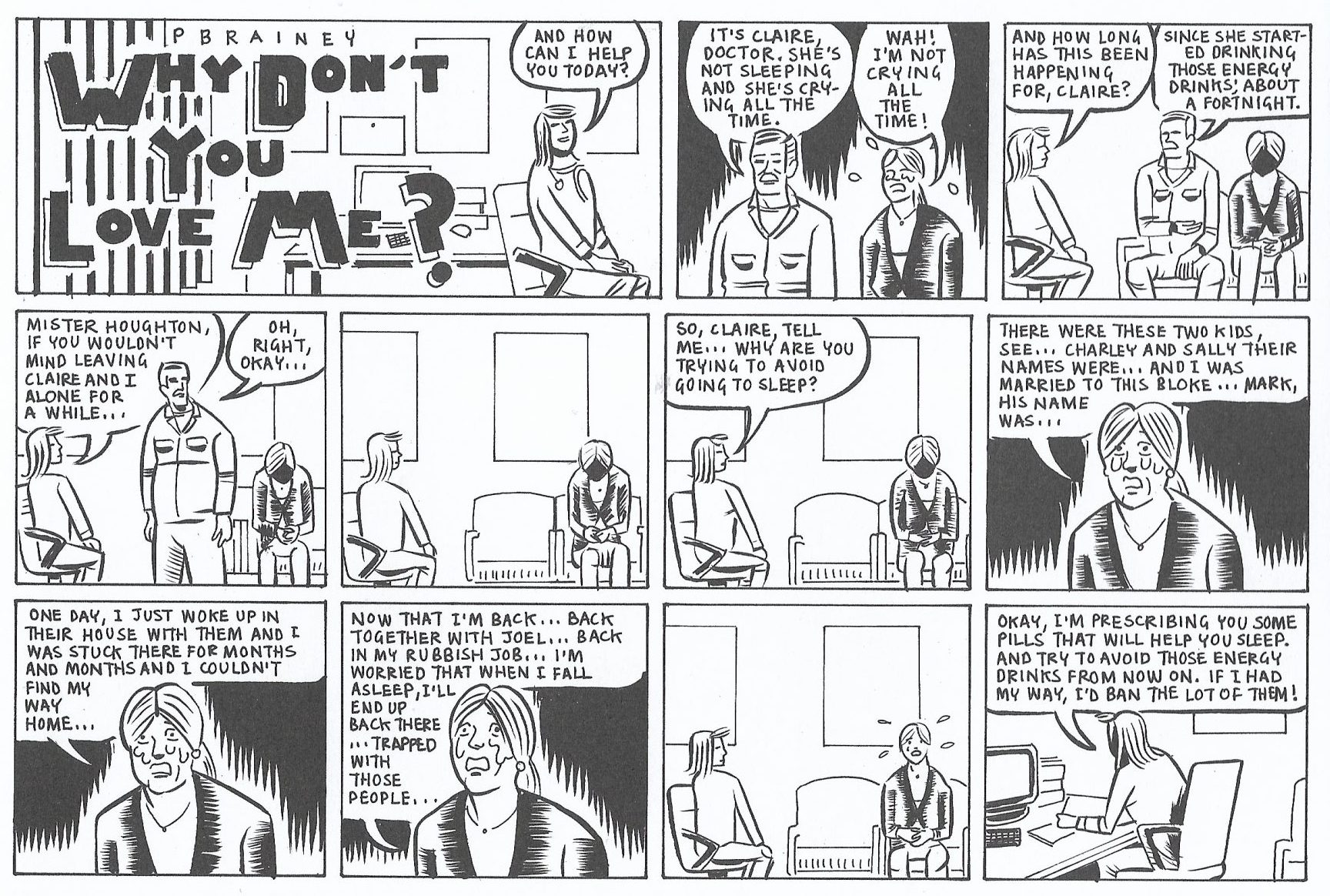

When we begin Why Don’t You Love Me?, we meet Mark and Claire, middle-aged spouses in a dysfunctional relationship. Claire is an alcoholic and clinically depressed. She is often depicted with her face lost in black shadow, a representation that can feel frightening and heartbreaking. She loathes Mark, a bespectacled and nebbish website manager who takes work off to endlessly enable Claire and bear the brunt of the parenting of their two children, Charley and Sally, both of whom are neglected and verbally abused by Mark and Claire.

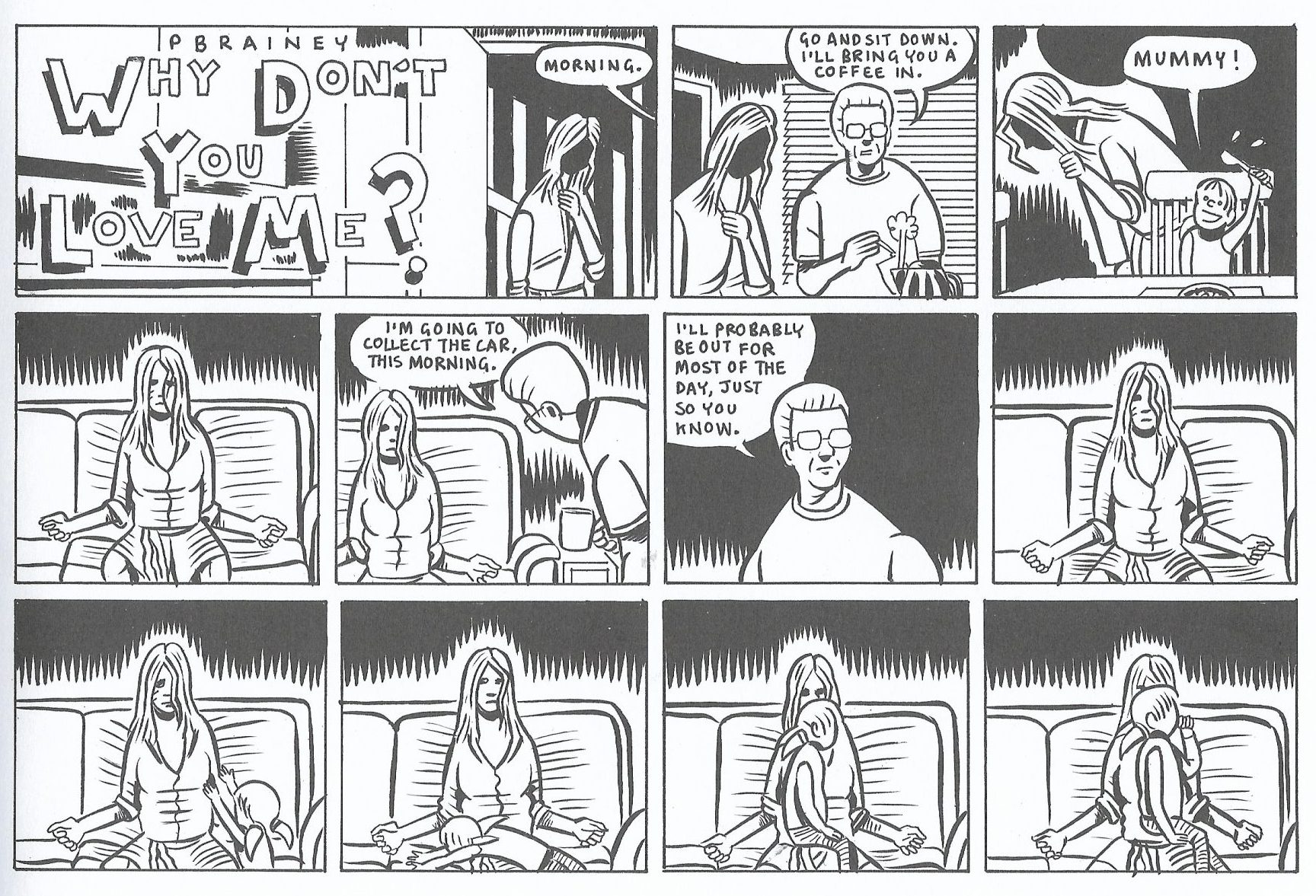

Much of the experience of reading the first half of the book involves an oscillation of pathos and bewilderment, sometimes encountering Claire at a moment of distinct pain and depression that renders her human, but other times appearing baffled by her cruelty. Rainey is fearless and remarkable in these instances, because he manages to make us empathize (at select times) with Claire or Mark, despite their cruelty, while also representing cruelty unsentimentally. Here, for example, we feel our hearts break for Charley, Sally and Claire:

It’s the kind of page that could make you cry. The pacing is perfect: the movement of Claire from silence to silence in the kitchen and into the living room, quasi-meditating in a posture of pain, numbness and inability to function. In the first panel of the bottom tier there is a slight saddening of her features when she acknowledges her daughter’s presence, before she moves back into a state of near-mutism. It’s agonizing and crushing.

Rainey’s characterizations, as in the example above, are always on the mark. His sharp lines capture character in a deft way, and over time we feel like we know these people well. When Mark takes his foreboding and his mug of coffee into the living room, for example, to engage in another useless argument with Claire, or when he has another awkward conversation with his workmates (the dialogue is always pitch-perfect, full of office speak and fakery), he is someone from our lives: a distinct character with a recognizable gait, someone we both feel for and loathe. And we feel like we know Claire too, who grows reckless in her total unease with life and depression and begins an affair with a neighbor. There is no idealistic spark to these characters, or for that matter anything the first half of the book, and Rainey intends it that way. This cruelty is magnified by Rainey’s decision to represent the narrative in daily comic strips, like a Prince Valiant about relentless misery.

But what do we make of the second half of the graphic novel, where we learn that the first half has been taking place in an alternative universe, and that Mark and Claire live very different lives? There is a feeling of wonder and haunting, like a panel pressed back to show an entirely unsuspected room. It’s often been commented that for the rules of science fiction to work, they have to be anchored in believable aspects of the real world. When we reach the second half of the book, we have been so immersed in the believable details of these characters’ lives that the gradual move into new lives is even more strange because it feels plausible, even as we know at another level that it is not plausible but stunningly weird. When we start to realize what is happening, we look back upon the pain of the first half, as if seeing it from a less torturous angle - like a memory, retrospectively, in a much different light. Why Don’t You Love Me? then becomes looser, a different animal: less about tedium and hopelessness in a modern world, and more about hope and possibility in multiple worlds, including the nuclear kind.

The post Why Don’t You Love Me? appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment