Elizabeth Colomba’s and Aurélie Lévy’s Queenie: Godmother of Harlem is a story as complex and captivating as its leading lady: Stephanie St. Clair, a.k.a. Queenie. Bound in a black and gold Art Deco-style hard cover, the text promises glitter and glamour, but its stark black and white interior delivers the gruesome reality of the American dream: racism, violence, mob rule, and injustice. Set in the twilight of the Prohibition era and the Harlem Renaissance, against the backdrop of the Great Depression, Queenie portrays a desperate and deteriorating society not unlike ours. At the heart of these circumstances is one woman’s determination to play the hand she’s been dealt, “Black, female, and poor” (62), and win against all odds.

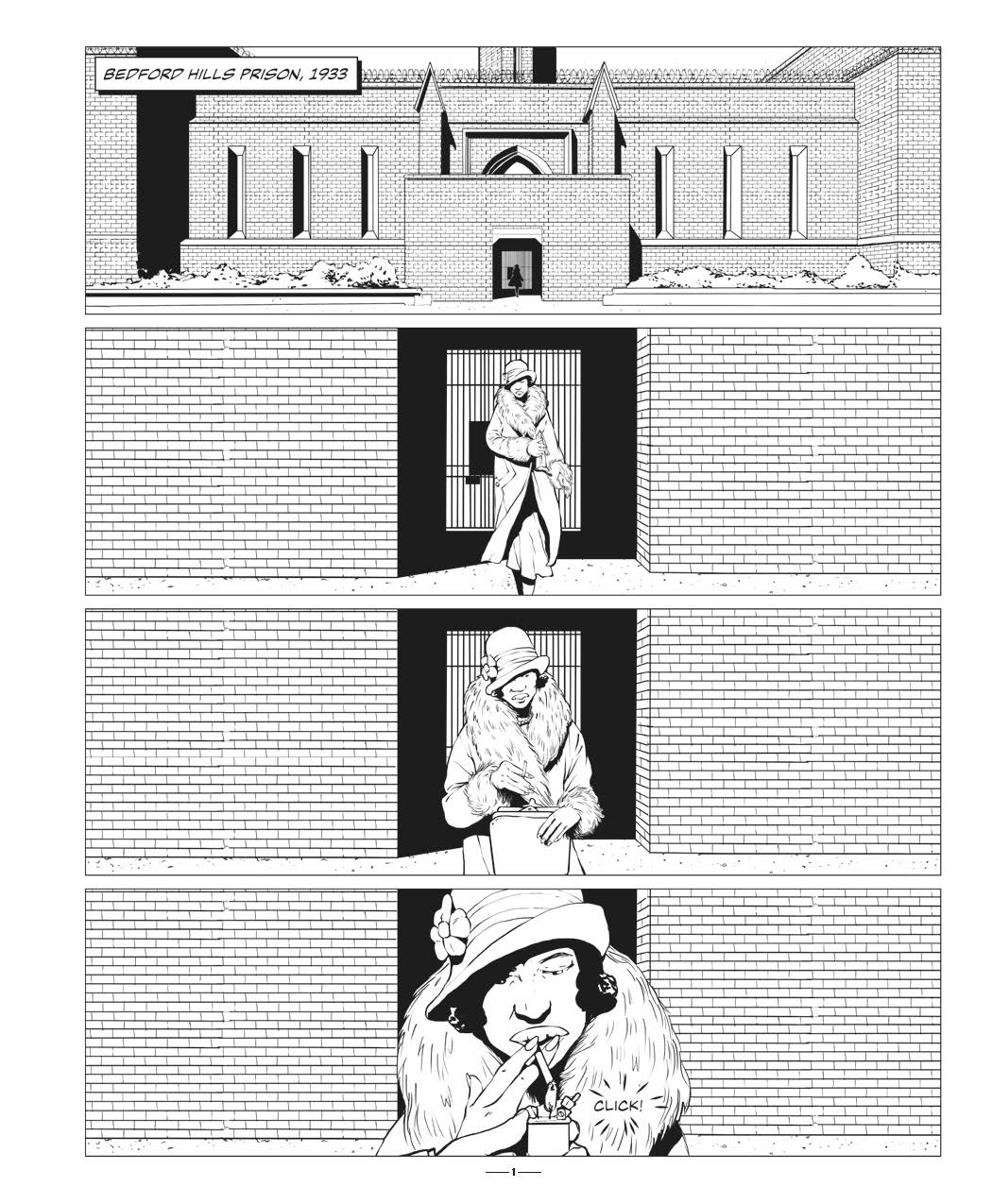

The first page of Queenie tells the reader everything they need to know about the story to come and the woman at the center of it. In the very first panel of the book, Bedford Hills Prison looms large - a fortress of bricks and battlements. The building represents everything American society purports to value: justice, defense, strength. But this institutionalized ideology is corrupt, meant to keep the marginalized, disenfranchised, and unwanted incarcerated and powerless by any means necessary. This idea is emphasized by the minuscule silhouette of a figure against the bars in the bowels of this fortress. However, as the page progresses, the immaculate and refined figure of Stephanie St. Clair draws closer to the reader, obscuring the prison’s uniform brick pattern with her marvelously curvaceous linework. This inversion of the institutional image in favor of the personal image enacts the reversal of power undertaken by the narrative. Stephanie’s personal power to bend and curve around the rigid structures of discriminatory institutions will prove to be her greatest strength and most captivating characteristic. Similarly, her transformation from an obscure silhouette to a detailed figure resplendent in felt hat and furs, full of agency and subjectivity, performs the critical upending of erasure central to this story. As gangsters like Dutch Schutlz and Lucky Luciano attempt to erase Queenie from the racketeering business and history entire, Queenie and her storytellers undertake a complex side-step that turns into a mesmerizing dance of survival and historicity.

A tale largely about performance and media, Columba and Lévy harness the power of images both to frame and overturn the reader’s ideologies, much like the scrupulous Queenie. Queenie understands the power of personal image, wanting to “project wealth, power, and confidence” (19) through her image: Who you are is who you present yourself to be. She also understands the power behind disseminating counter-narratives to correct systemic injustice, using news articles to dismantle corrupt community figures (26): You are what society believes you to be. These two ideologies are in constant conflict throughout the text and speak to the racialized lens through which people of color have been viewed throughout history.

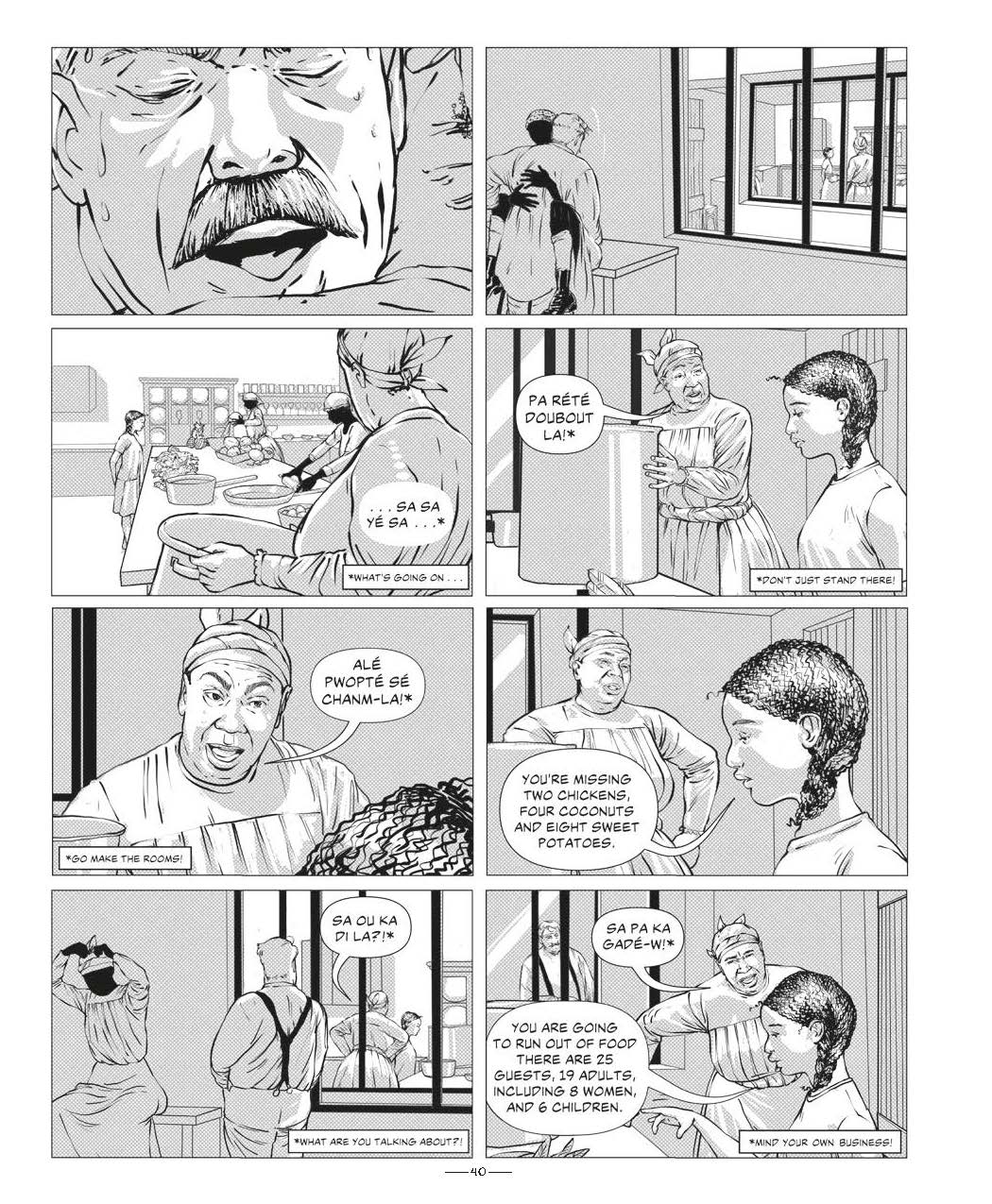

Columba and Lévy show this conflict through silhouette and the manipulation of background and foreground action. Though much of the narrative is set in Harlem in the 1930s, the reader also follows Queenie as a young girl on a plantation in Martinique. During these flashback sequences, Black characters in the background are depicted as silhouette figures in uniform. This depiction provides a commentary on the erased subjectivity of colonized individuals while simultaneously commenting on the effacing racialized lens through which individuals of color are seen both in Queenie’s segregated society and in contemporary society. The design of the silhouette figures, and their position in the background, imitates the value that dominant or colonizing groups attribute to people of color. This positioning inevitably leaves such individuals vulnerable to any number of injustices and atrocities.

However, it is the background position that Queenie and her community have been forced into that allows her to enact her own justice. Creating a community network of individuals operating in the wings of the dominant society, Queenie leverages that marginal position to safeguard herself, her community, and exact the justice that continually eludes them. Columba and Lévy harness this same position in their narrative approach, allowing the reader to see what they want to see, and not what has been right in front of their eyes all along. In this way, Queenie conducts a magnificent visual sleight of hand, prompting the reader to question their own assumptions and examine the way they consume visual information.

The brilliance of Queenie is that Columba and Lévy participate in the cultural dissemination of visual media while simultaneously examining its impacts. This book contends with the impact of visual mass media on societal values, especially as it concerns people of color, while simultaneously creating a narrative that brings into focus a woman of color erased from the cultural history of the Prohibition era. Queenie is as much about the impact of stereotypical representations of people of color as it is about the purposeful erasure of people of color from the larger cultural narrative. This negotiation is deftly shown in a double-page sequence in which Queenie and Bumpy meet Harris at a theatre playing Fighting Caravans - a generic cowboy film where characterized Indigenous people are cast as the antagonists of the American west. This two-page sequence not only aligns the oppression of Indigenous individuals with Black individuals in America, but also the power fantasies and values disseminated by visual narratives about these communities. Getting down off his horse and removing the added asterisk from the scene, the Indigenous character directly confronts the reader about the power fantasies and prejudicial values that visual narratives engender and their culpability in constructing societies that systematically disenfranchise people of color as part of a nation-building mythology. As the sequence ends, both the viewers (Queenie and Bumpy) and the viewed (the Indigenous character) are constrained into a narrow final panel, a silent loop enacting the very essence of their marginalization.

Columba and Lévy suggest that such prejudicial representations are far from innocent and have echoing consequences for people of color across history. In a scene that echoes the cowboy narrative sentiments of Fighting Caravans, while traveling from New York to Florida, Queenie’s bus is intercepted by the Klu Klux Klan. The hyper-realistic and even cinematic style of the scene echoes a modernized version of Fighting Caravans - the long panels mimicking a movie screen. In this sequence, self-styled cowboys, the KKK on horseback, circle a bus carrying Black passengers - enacting their own awful power fantasies, but certainly not justice. Horrifying scenes of lynching, burning and raping fill the American landscape. A pinned-down Stephanie St. Clair gasps “I can’t breathe” as a Klansman sits on her neck, a visual image that echoes the death of George Floyd in 2020 (90). An extreme close-up of Queenie’s pupil reflects the silhouette of a lynched man while a bus full of white passengers drives by the scene - resolutely staring forward, refusing to see or act upon this atrocity in plain view. Like the previous sequence of Queenie and Bumpy at the theatre, the silhouette of the lynched man is shown in a final narrow panel. Through these paired sequences, the interplay between watcher and watched is folded back upon the reader, who passively watches the story unfold before their eyes.

Columba’s and Lévy’s Queenie is a compelling and nuanced visual narrative that encourages the reader to look carefully, not be a passive viewer, and not be conned by a system working to disenfranchise large portions of the population.

The post Queenie: Godmother of Harlem appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment