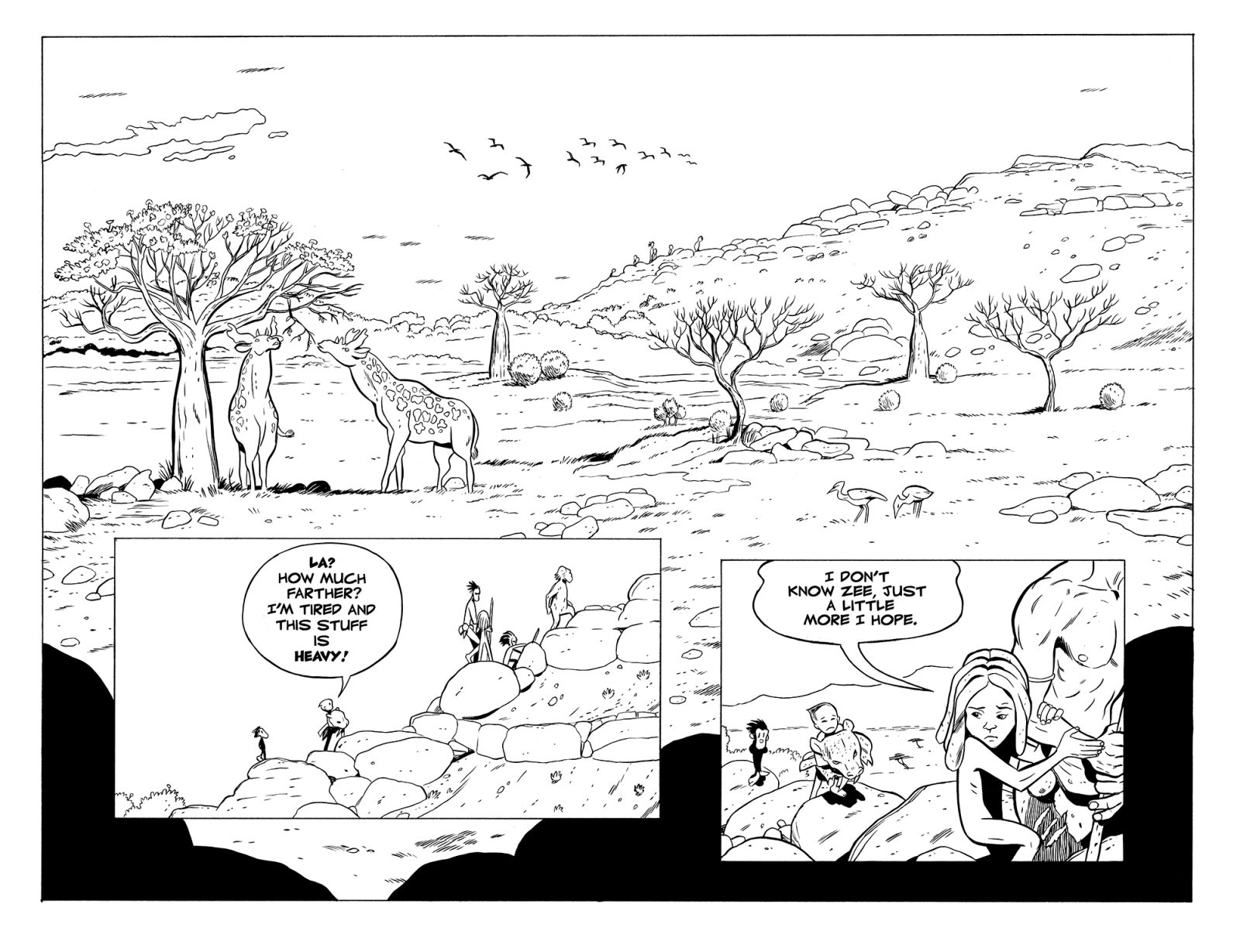

Two million years ago. A time almost beyond imagination. Land stretches out as far as the eye can see. Plains and grasses, rivers and waterfalls, trees and bushes. This is the land’s architecture and the building blocks of Jeff Smith’s Fight for Family, the second installment of the TUKI series. From a viewpoint high above the savannah, the land can appear deceptively empty, but Smith’s artwork captures its starkness and beauty. However, as TUKI moves from the savannah to the jungle, Smith shows that this land is inhabited by various human species, along with predators and prey, lore and new technology–but also love, loyalty, and laughter. The fight for family–the determination to stay together, the willingness to care and cooperate–takes center stage in Smith’s latest. As the artist guides the reader through lands plagued by disastrous climate change, zealots, and violent traditionalists, we come to see how full the land really is, and how 2 million BCE is eerily similar to 2022 CE.

The fight for family, the central theme of this book, is not the struggle of a group of related members. Rather, it is the resolve of a group of orphans and misfits to depend on one another and find strength in their differences. Fight for Family resonates with the notion that the people who stick by you when times are hardest are your true family–that a sense of belonging is not found in a place, but in a person. Tuki, a lone wanderer and giant killer, stands by his conviction that he will find the fabled MOAB, the Motherherd of all Buffalo, which will sustain his people. La, Zee, and Ree-nan are orphaned siblings whose people are violently murdered by the hairy, fire-fearing Habiline (or: Habos). An old Habo, Doc, the Keeper of the Lore, has been exiled to a grotto because of his age, uncleanliness, and disturbing prophecies. The tiny Kwarell has been ostracized by his fellow Pithies for reasons yet unknown. However, when Tuki hurts his leg, La heals it. Zee and Ree-nan help by making sets of Tuki’s sling for the whole party. The group hunts and gathers to sustain each other, and when Zee and La are kidnapped, the rest band together to get them back.

Smith’s work is not only about the importance of (chosen) family, but also the importance of story. Bonds are created through attempted communication, whether verbal or nonverbal. When La recounts her escape from camp during the Habiline attack, both Tuki and the reader gain a new appreciation for her courage, pain, and fear. When Tuki demonstrates and explains how to capture the fire force, Ree-nan learns to use, appreciate, and respect a new technology. When Doc admits the truth of his isolation, he bonds to the others through compassion. Kwarell, who has either not yet developed complex vocalizations like the others, or otherwise cannot speak their shared language, communicates important information by miming–assisting the others in tracking down the kidnapped Zee and Ree-nan. As Smith understands, creating and sharing stories are foundational to human evolution.

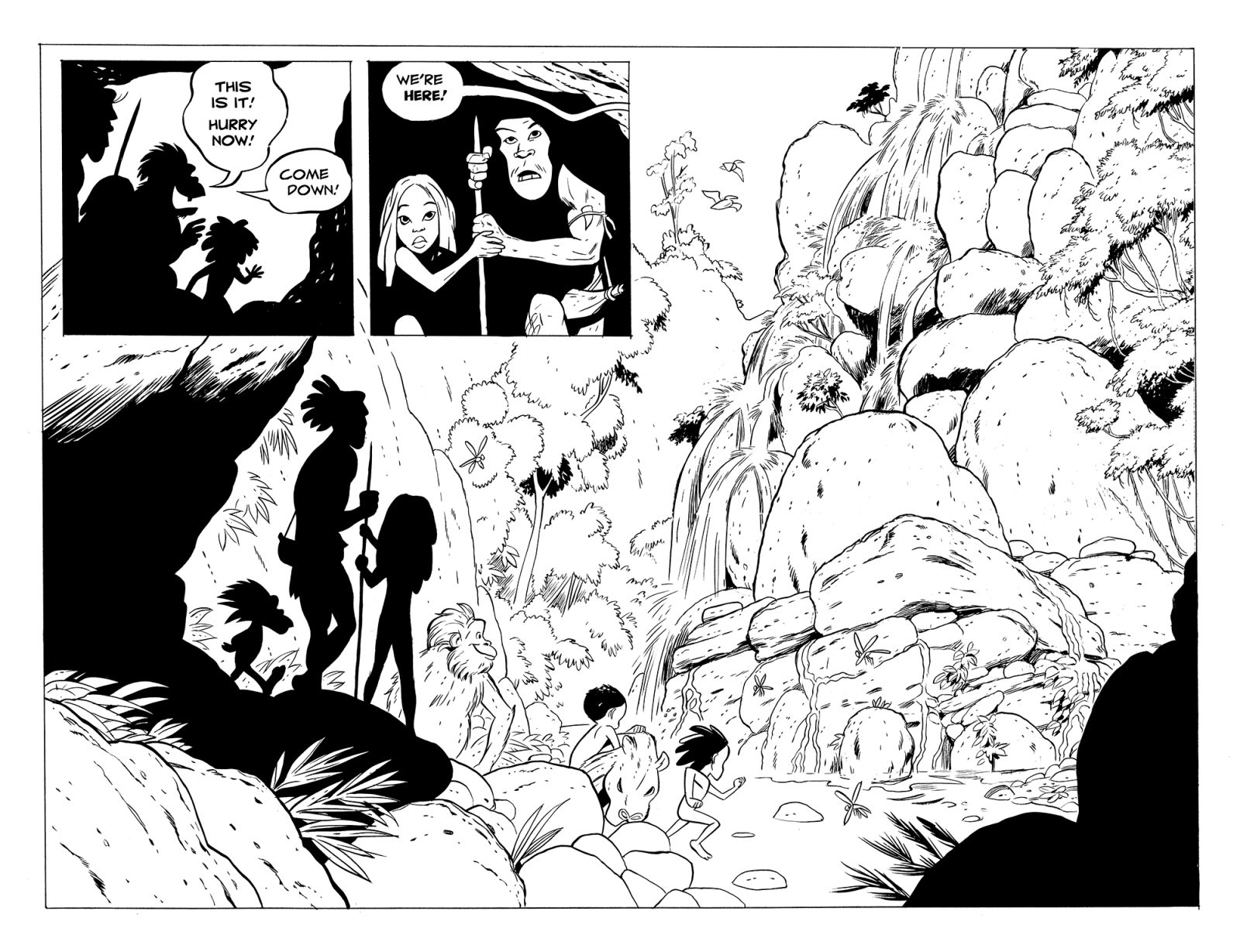

Smith’s tools may be humble–paper, pen, ink, brush–but he wields them like the unrivalled craftsman he is. This story, told in landscape, uses the page orientation to communicate an expansive environment and epic story. Smith’s iconic black and white linework possesses an unparalleled degree of precision and deliberation, which he uses to usher the story forward through a high contrast visual world, firmly holding the reader’s eye in place. He presents the lush expanse of the prehistoric landscape through the delicate brushstrokes of dragonfly wings and background fauna. This delicate linework is carefully balanced alongside Smith’s silhouette work, rendering each character instantly recognizable within the detailed landscape. Smith manages a highly controlled reading path, steadily moving the reader’s eye, even in splash pages. Smith’s silhouette work also communicates action, fear, and suspense. Hidden in the hollow of some overhanging rocks, La, Zee and Ree-nan evade a prowling Habiline warrior. The imposing silhouette of the warrior with its low-slung trophy skulls and delicate hairs, nose sniffing against the trees, transfers the intensity of the moment from the characters to the reader. Much like the characters, the reader waits with bated breath.

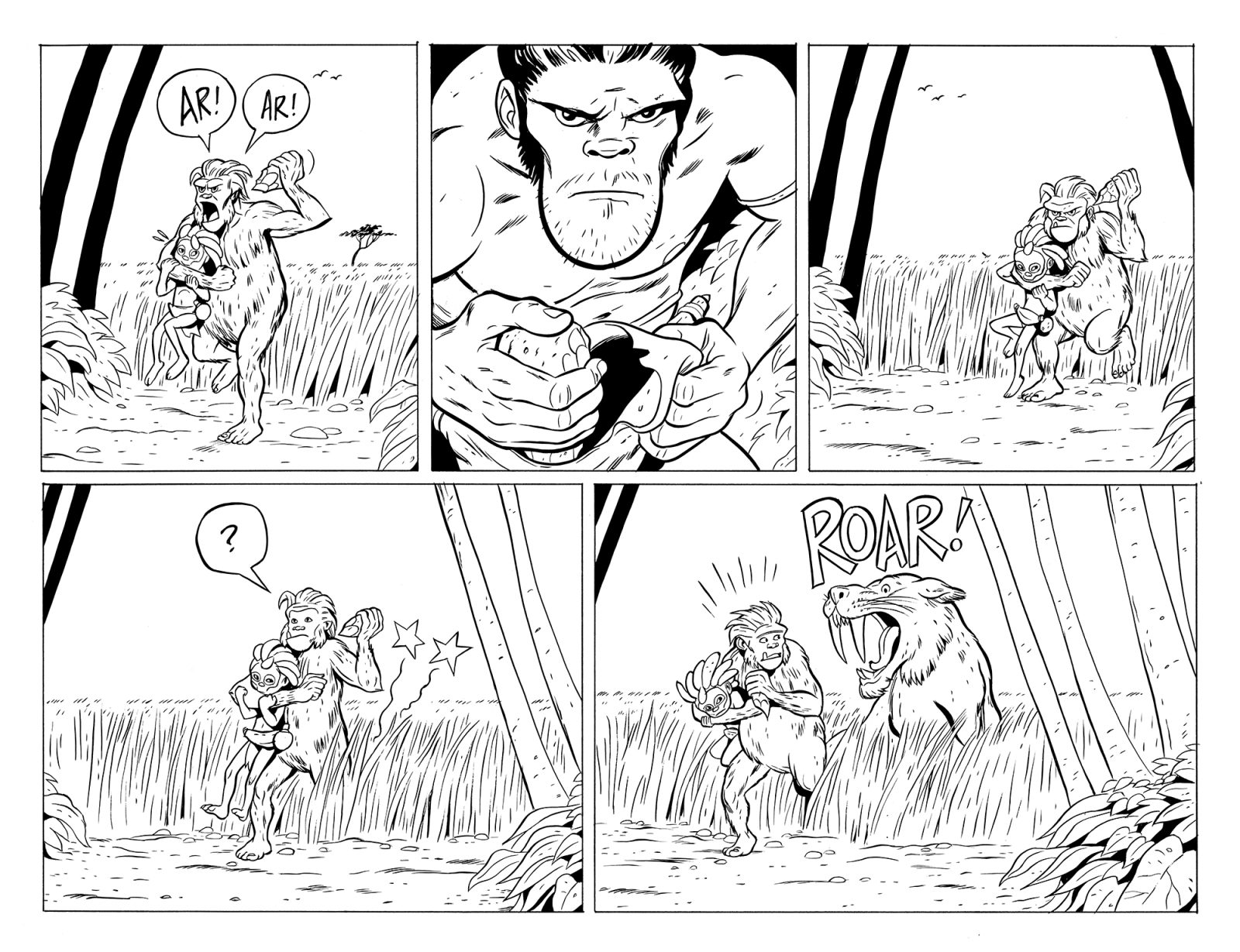

Smith captures urgency with clarity, both in stillness and in motion, through gestural composition and sequential timing. Smith’s gestural composition is elegant and dynamic. TUKI reads as a heroic and epic adventure because of the dynamism of Smith’s figural choices. Tuki is everything that you want a heroic protagonist in a comic to be–strong, fast, fearless, acrobatic. The visual action sequences come across effortlessly, believably depicting a homo erectus moving through and navigating this ancient landscape. However, even the most beautifully drawn form in motion cannot convey a convincing sequential narrative without an impeccable sense of timing. Smith’s timing is what gives TUKI’s visual narrative its emotional impact, both in terms of its gravity and in terms of its levity.

Fight for Family is just what you would expect from the creator of Bone and RASL–an immersive, emotional, and delightful visual masterpiece. This is a story that will engage your sense of wonder and your reflection about the distant past, but also the current moment. In the wake of a climate in crisis, a global pandemic, and a pressing existential threat to our collective futures, Fight for Family reinforces ideologies of adaptability, communication, cooperation, and compassion–and it does so through a beautifully-crafted story you will wish to share far and wide.

The post TUKI: Fight for Family appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment