The one thing all celebrities have in common, it has been said, is that they are all absolutely incapable of taking care of themselves. Batman might seem self-sufficient until you take note of the butler, the bank account, and the endless queue of unpaid interns. Untethered from his support system, he’s just a guy that doesn’t know how to run his own errands—wouldn’t even cross his mind. The Batrope would rust and the fridge would overflow with spoiled ground turkey. In their depiction of Gotham City, Josh Simmons and Patrick Keck pit those deficiencies against Batman’s feverish megalomania. At one point, left behind in his deteriorating mansion for who knows how long, Batman takes a hot shower while wearing the cape, cowl, and utility belt. He doesn’t even take them off to masturbate.

Dream of the Bat anthologizes Josh Simmons’ and Patrick Keck’s unlicensed take on the Bat mythos, which began as a 2007 standalone by Simmons (Keck would join him later) but has taken on new life in the past five years, just as this exact archetype of public figure has taken up a particular space in American culture. The story itself more-or-less tracks Batman’s psychological deterioration as the Earth dies around him, but also, like, with a staggering amount of penis and shit. It could very easily come off as a novelty, if it not for the obvious care put in at every turn and the constant indicators that close reading will be rewarded.

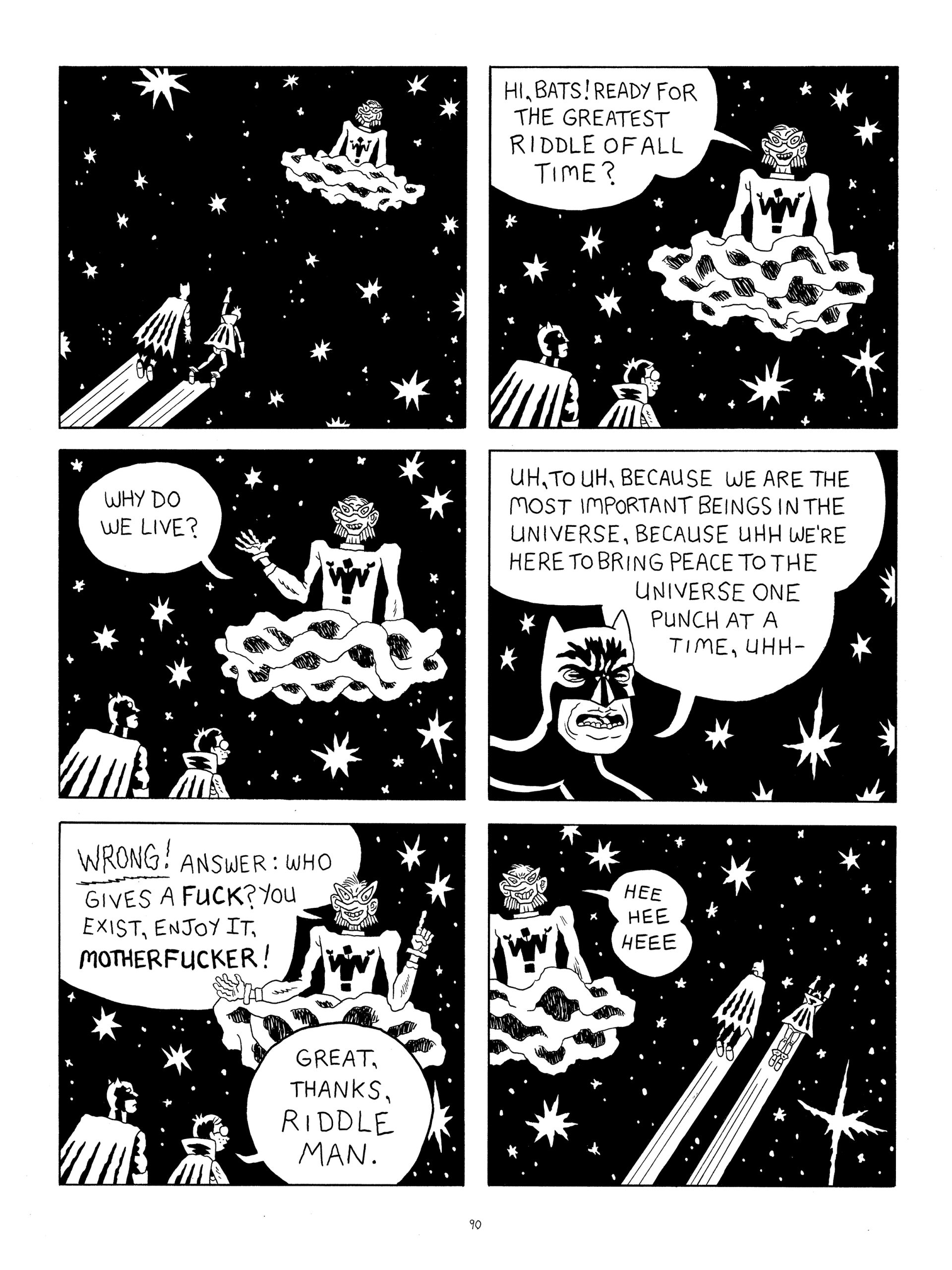

Simmons and Keck frame the comic in a way that fulfills the expectations of a typical Batman book, cycling through the rogues’ gallery and incorporating all the iconic Bat-signifiers. Simmons’ style is less parody than creating an off-brand version of the comics that you might find in the back of a dollar store, barely obscuring the source material. Batman is Bats, Joker is Joke Man, Riddler is Riddle Man, and so on until the whole thing feels like it’s on the corpse-zombie axis of the uncanny valley. One fight sequence features the sound effects Whunch! Chash! Clud! Fash! Boost! Turf! Bash! Flan! and Chud!! Yet the tone remains flexible enough to veer from dark comedy to existential dread to what appears to be, as Joe McCulloch suggests in his review of Twilight of the Bat, sincere homage.

Though each of the four self-contained issues has its own unique merits, the promise of Dream is that the final chapter—the only one not previously published—completes the arc and unearths new meaning for the previous episodes. The same mission gets picked up in book design itself, which features guest art, layouts, comic strips, and inside covers laying out a before and after of Gotham as rich as anything in the meat of the narrative. Holding it as an artifact, it feels like you’ve stumbled across a psychopath’s journal—in other words, perfectly reflective of Batman’s state of mind throughout Dream.

Dream of the Bat initially finds its hero at a time when the adrenaline has kicked all the way out. He’s curled up in a ball on a rooftop, fully depleted, feebly trying to hydrate from a bucket of rainwater. When Batman perches on the capstone of a tower to hunt criminals, Simmons draws him like a middle school kid waiting for the school bus with his knees tucked into his sweatshirt. A wellness check from Catwoman reveals Bats has been working on a “new Bat-device” to brand criminals for easy recognition. The punchline—who these criminals are, how he brands them, and the variety of law-abiding citizen reactions—is macabre and hilarious. But there’s something more at play than just a riff on Batman’s authoritarian sadism. The throughline here is the extreme lengths to which he will go to preserve his sense of identity, clinging to his core values—his intertwining ideals of justice and vengeance—as he treads water in a bottomless well of ego and ennui.

Simmons seems particularly interested in the effort it takes Bats to perform the superficially routine tasks readers tend to take for granted, rendering step-by-step precisely how he swings onto a building. There’s one panel that’s just Bats redistributing his weight to reach his grappling hook. As he climbs, his profile reveals an unshaven and emaciated husk of man. Everything feels freighted with effort, especially in contrast with Simmons’ Catwoman, who sprints along rooftops and hangs weightless in the air for a moment before diving toward the street. As things progress, a withered Batman continues to seek out and manufacture those demands on his body until they culminate in extreme self-mutilation. Elsewhere, a two-page strip included the book’s bonus material depicts Catwoman making Bats eat her feces in exchange for sexual gratification, which seems perfectly canonical in this world that is constantly contemplating even the everyday body horrors of shitting and fucking.

Mostly, this Batman is small. He is at all times displaced by the city and engulfed by the thick air. In the opening chapter, Simmons draws G— City as a dense Lower East Side tangle of crooked buildings and non-functional phone lines. Later, as it’s been hollowed out by firestorms and subsequently frozen into a kind of nuclear winter, Keck replaces Simmons’ stark expressionism with a landscape of unstable molecules; an environment where the corpses are nearly indistinguishable from metal, fiber, and glass. By the end, everything is desolate and hopeless. As the world burns, Bats only becomes more insular.

The knockout blow comes when the new, final chapter provides the satisfying resolution that the first three didn’t even necessarily need. Simmons and Keck manage to do a lot of things that would be tough to pull off even if the pilot episode hadn’t premiered a decade and a half earlier: they introduce characters we instinctively knew had always been missing; complete the world-building only previously hinted at; and hilariously pay off Batman’s long descent into madness, laying out What It All Means in a way that simultaneously fulfills and undercuts expectations. Without giving too much away, it culminates in a stunning sort of fractal ouroboros of Batman eternally eating his own origin story.

On the surface it might seem as if Dream of the Bat simply plays the usual Bat-crit satirical hits that have been in heavy rotation since the '80s. His fascist tendencies, monomania, sexual tension with the Joker (which McCulloch also goes in-depth on), and refusal to ever actually heal from the death of his parents all get major airtime. But, for one thing, Simmons and Keck manage to take many of these to surprising and unsettling heights. For another, the sense is that everything happening on the fringes is equally important. It’s not so much about the Batman as it is about the absurdity of one massive ego raging against the decaying universe.

The post Dream of the Bat appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment