(SPOT.ph) If your older family members are of a certain generation, then they might have that natural ability to locate someone’s hometown just by knowing their surname. Back when family reunions weren’t done on Zoom, you may have heard a conversation with a line that goes, “Ah, [insert surname here]—taga-[insert location here] ang mga 'yan.” Sadly, we can’t say the same for later generations, when what we usually know about the people on our social media feed is what they ate this week. But if one were to pursue the thought “What’s in a name?” as Shakespeare once wrote, you can uncover an interesting narrative around your own surname that could reveal much about your family ties as well as our nation’s history.

For those who are Chinese Filipino, you may have heard about how your ancestors bought your present surname. No matter how strange this might sound today, it all starts to make sense once you read historical accounts that go back to colonial times, particularly during the Spanish and American occupations of the Philippines.

The Origins of Your Surname: A Quick History

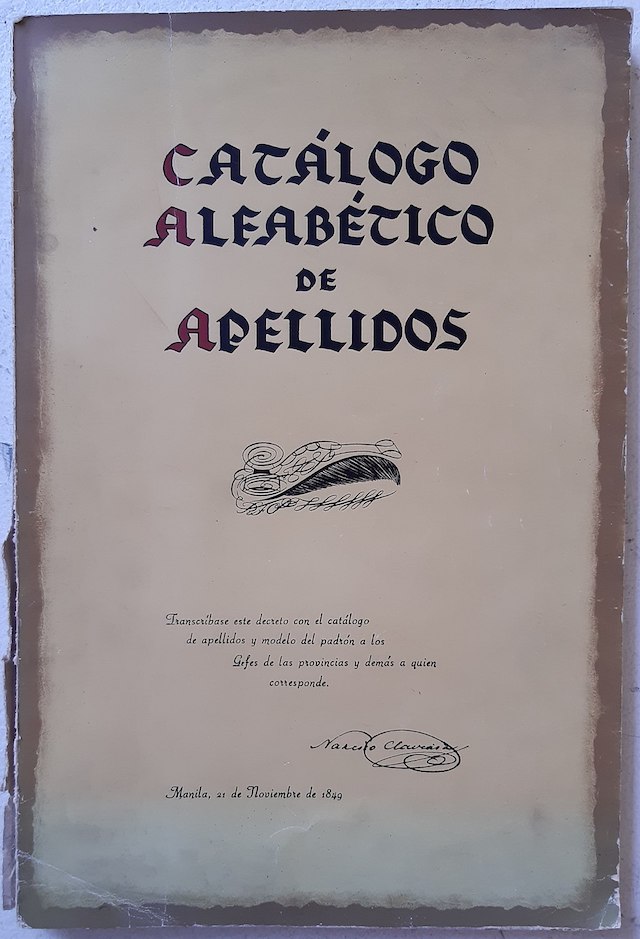

The history of names and how we got them takes us back to the year 1849, with a Spanish governor general named Narciso Claveria and a document called Catalogo Alfabetico de Apellidos (a digital version of which can be accessed via the Filipinas Heritage Library). Fun fact: There are towns in which all the surnames of the people begin with the same letter, says Domingo Abella in an introduction to the Catalogo for its reprinting in 1973.

It's one explanation for why some people in our families seem to have that instinct for matching surnames with their respective hometowns. In an 1849 decree, Claveria “simply allocated to each town a number of pages from the Catalogo from which the people chose their surnames,” the purpose of which was to “end the confusion in the administration of justice, government, finance, and public order” on the part of the Spanish colonizers.

A portion of Claveria’s “Decree of 21 November 1849” even states that “Natives of Spanish, indigenous, or Chinese origin who already have a surname may retain it and pass it on to their descendants.” As historian Ambeth Ocampo notes, this decree is the reason why “…some very ethnic-looking people today have Spanish surnames like Gonzalez, Gutierrez, Enriquez, or Romualdez, while some mestizo or Chinese-looking Pinoys go by names of pre-Spanish nobility like Gatbonton, Gatchalian, Gatdula, or Gatmaitan, or names with traits of pre-Spanish warriors: Macaspac (destroyer), Macatunaw (a person who can melt metal), Macatangay (a person who can grab or capture), Macapagal (tireless) or the self-explanatory Catacutan, referring to someone who was to be feared.”

Hector Santos, who compiled a Catalog of Filipino Names in 1998, attributes three-syllable Chinese surnames like Cojuangco or Teehankee back to the 1849 decree, saying that “… early Chinese Filipino families took on the complete name of their patriarch, thus their names had three syllables. These are truly Filipino surnames and don't exist anywhere else in the world.” Santos goes on to mention how the common occurrence of names ending in -co and -ko, for example, was “… a title of respect given to someone like an elder, or an older brother,” among other historical accounts.

Why Chinese Filipinos Changed Their Surnames

Chinese presence in the Philippines was much earlier on established by way of trade even before the Spaniards came here in 1521. Chinese settlers would later seek refuge away from their homeland, faced with the reality that “… they could never expect protection from China except from their own clan or family.” It would make sense then, that one layer of “protection” would have been to change their name until a time came that they would feel safe enough to finally stay in one place.

But the next centuries would prove not to be entirely peaceful for the Chinese—for example in the case of the massacre of 1603 which was said to have led survivors to flee to Guagua and other towns in Pampanga in order to hide their identity. They adopted “two-syllable Chinese surnames ending in ‘son’ or ‘zon’ such as Hizon, Dizon, Henson, Lacson, Pecson, Liongson, Guanzon, Jocson, and Bonzon.”

A classification system was then put in place by the Spaniards and later on adapted by the Americans who took over in 1898, which further perpetuated this separation of “Chinese” and “Filipino”: There were the sangleyes (“Chinese”), mestizos (the offspring of Chinese men and local women), and the “indios” (the natives). According to the journal article The "Chinese" and the "Mestizos" of the Philippines: Towards a New Interpretation, the American colonial government placed the ‘mestizos’ and ‘indios’ under the category of ‘Filipinos,’ while the ‘Chinese’ were regarded as ‘aliens’ to simplify ethnic classification.

Ultimately, it would be the implementation of the Chinese Exclusion Act which would compel the Chinese in the Philippines to buy Filipino surnames. The Act which was passed by the U.S. Congress in 1902 “… extended to the Philippines the prohibition against the entry of Chinese to the United States. This background to American policy and the restrictive policies of the Spanish colonial government were the factors which contained the flow of Chinese immigration in the Philippines.” George H. Weightman notes how “practices associated with accommodation to exclusion evasion contributed to the widespread phenomenon of aliases among the Philippine Chinese. Informants repeatedly speak of ‘real’ or ‘stone names’ (i.e., the name used o tomb stones) and ‘false’ or ‘paper names’ used on official forms and registrations. Many Chinese appear to have several Chinese and Filipino names.”

Kyoto University professor Caroline Hau summarizes what became of the previously established social classifications after the age of independence: “… the descendants of Chinese mestizos who had become Hispanized in the 19th century had become Americanized in the 20th… Newspapers of the time routinely used words like ‘Sinos’ as a blanket term to refer to naturalized and alien Chinese, and to Chinese as well as Chinese mestizos… While some mestizos came to be seen as and lumped together with the ‘Chinese,’ the term mestizo itself in popular usage was stripped of its sociological and historical reference to ‘Chinese’ and came to be increasingly ascribed to Filipinos of mainly white (American or European) ancestry…”

Clearly, what we might assume today of what it means to be Filipino, Chinese, or Chinese Filipino via a study of surnames is defined by such moments in the past that cannot be so easily plotted on a straight line, let alone an article like this one. But here's some food for thought: The annual Forbes “50 Richest” regularly features a not-so-surprising list of names, among them families with Chinese ancestry who have held those positions for as long as one can remember. But perhaps what we all need to realize—and this includes us non-billionaire folk—is that beyond the prestige of wanting to make a name for ourselves lies the importance of your character as an individual and how you treat others, which far outweighs the value of the name that happens to be on your birth certificate.

[ArticleReco:{"articles":["87062","87063","87061","87050"], "widget":"Hot Stories You Might Have Missed"}]

Hey, Spotters! Check us out on Viber to join our Community and subscribe to our Chatbot.

Source: Spot PH

No comments:

Post a Comment