Everybody at some level believes in it. It's a deeply seductive image. The image that we all want, as oppressed people, is an image of our masters finally loving us and recognizing our humanity. It is this image that keeps prostitutes with their pimps, the colonized with their colonizers and battered women with their batterers. Everybody dreams of one day being safe.

-Anthony Farley, legal scholar, quoted in Silent Covenants: Brown v. Board of Education and the Unfulfilled Hopes for Racial Reform, a 2004 book by Derrick Bell, one of the originators of Critical Race Theory in the United States of America

* * *

What is a ghost? A potent metaphor can represent a great number of things, and the idea of the ghost can run the gamut from cultural memory to unresolved trauma. But at its core, the ghost is the idea of that which is left behind. It is about some measure of legacy. It is about a legacy that haunts us; beyond the grave but everlasting. That which is ‘gone’ yet immortal.

At the heart of the ghost story is being able to see the things which haunt us, which possess us, whose histories are woven into the very lands we tread upon. The invisible becomes visible in ghost stories; the past is awake and informing the present. This is the invisible legacy of our world.

And what greater legacy is there than that of horrific oppression justified through racist and xenophobic doctrine? What poisons our future more than centuries of colonial cruelty and bigoted thought, which diminishes so many for the sake of exploitation and power? What haunts us more, particularly in this current cultural moment, than the weight of that rot? It is the most horrific legacy imaginable.

And this is what Infidel, a modern spin on the ghost story, takes as its subject matter.

Published in 2018 by Image Comics, Infidel comes from writer Pornsak Pichetshote, artist Aaron Campbell, colorist and editor José Villarrubia, and letterer Jeff Powell. It’s a work about the invisible forces that haunt us all, spun into a striking genre story: the matter of race through the lens of horror, as many have done before.

The man, Ahmad Shahzad, is blocks away when it happens. The police find him, and he dies in a shootout. The investigation afterwards reports the man visited an ISIS website at one point. He also visited numerous anarchist websites, and no one truly knows why he he had those explosives, but the dominant narrative in the press is that of a typical Brown terrorist. Only his corpse remains.

The apartment complex itself remains standing, but seven people die in the explosion: an elderly White couple, Abe, a disgraced ex-academic, and his wife Faith; another White couple, Mitchell and Ashley, the former a Harvard graduate and failing writer, the latter a failing actor; and, lastly, a Korean-American family of three, the names of whom we never learn.

These are all the dead.

Months pass, and new people move into the complex, now half-repaired with units at a deep discount. Aisha, a Pakistani-American woman, moves in with her soon-to-be mother-in-law, Leslie, who is White, and lived through the explosion. Aisha is joined by Tom, her partner, and Tom's daughter, Kris. Aisha is an editor overseeing Star Wars cookbooks, while Tom works in film. Aisha’s lifelong best friend, a Black woman named Medina, and her roommate, an Asian man named Ethan, also join them in the complex. Medina is passionate about activism and studies architecture, while Ethan is a novelist.

Sure, the place is creepy, and the whole explosion incident was scary, but the rent’s real cheap. What’s the harm? What’s the worst that could happen?

So begins Infidel.

Things are... off. Aisha’s freshly-bought meat spoils with uncanny speed. She has strange, horrific dreams filled with chilling monstrosities. She questions her sanity. Is it her medication? These things all seem targeted, and Aisha feels isolated, alone, with no one to really turn to.

What is even happening? What is all this?

At its core, Infidel is very much a post-9/11 haunted house story, a ghost story told through a contemporary racial lens, predominantly focused on a BIPOC cast in pernicious circumstances. We have a Pakistani-American, an African-American and an Asian-American as the key figures. Central to the work is the corrosive conceit of Islamophobia, particularly during the Trump presidency, as both Aisha and Medina, our two key leading women, are Muslim. (Aisha is deeply religious, while Medina no longer practices.)

Everything in Infidel is about these people, how they relate to each other, and how they see the world in relation to them - particularly in contrast to the White people around them. But also, even more importantly, it’s about the opposite: how the world sees them. The monsters, the ghosts of the dead, are very specifically designed to help us explore this in genre terms.

In its first few chapters, Infidel seems like it could be nothing more than your time-tested tale of the mother-in-law vs. the wife-to-be, with a racial undercurrent; there are some early suggestions that Leslie is gaslighting Aisha into only thinking there are ghosts in the building. Leslie has been prone to Islamophobic outbursts, so she is an easy, expected choice for the antagonist.

But the book never goes there. In fact, the character who sets this dynamic up for us as a red herring is Tom, Aisha’s partner, who is constantly going off about his mum. Tom is understandably disillusioned with his mother, having found out she’d looked into seizing custody of Kris: "he got scary," we are told, after the child's mother died. The hurt of that plays out in a way that leaves no room or possibility for Tom seeing his mother as an actual person capable of being more than what he is determined she is. Tom places his own certainty about his mother's ill intent above Aisha’s own experience as a Brown Muslim woman who’s dealt with racist shit all her life. The Secretly Evil Racist Mother-In-Law is an obvious route the book is not interested in taking, for that would betray what it actually is trying to do. Of course bigotry is bad; of course racism is horrid; of course Islamophobia and xenophobia of any sort is evil. Infidel isn’t trying to just didactically smack you with these things, and neither does it hinge itself on them. It operates under the assumption that these are obvious, evident things, and constructs something more nuanced to get at the questions it actually wants to and needs to ask:

How does racism permeate the space around us, beyond the glaringly obvious ways? How does it perpetuate itself and grow stronger? And how have we been conditioned to consider race? How does that shape our realities?

Leslie, for example, has internalized racist ideas and beliefs, and has bought into xenophobic rhetoric about Muslims. She’s a woman who feels fear, whose grip on her bag tightens when a Black man passes by her on the train. She is an old White woman who has a lot of unlearning to do, which is also why she feels intense shame after the man has passed. It’s why she regrets her hateful parroting of Islamophobia. She knows she has been conditioned to think this way, and is actively trying to do better, to be better, something Tom doesn't believe she had the capacity for, though Aisha does.

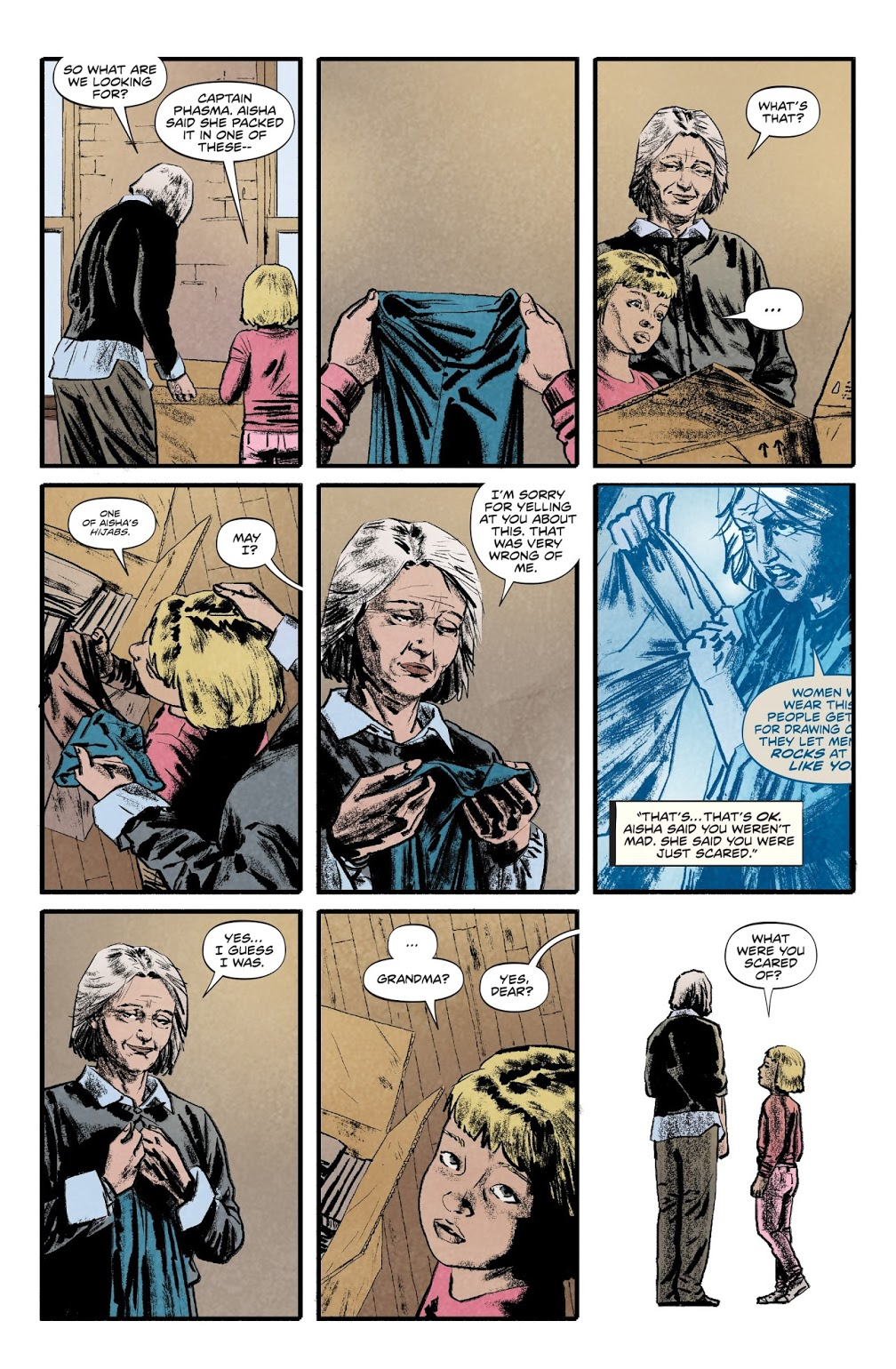

Aisha understands that Leslie's way of thinking is not some rare thing, but quite predictably ordinary. That people internalize racism and xenophobia through their prevalence in culture and by structures and systems. Aisha feels Leslie is worth the effort, and can change - that she is capable of seeing Aisha’s own humanity and interiority, and is capable of breaking free of what she’d been taught. And that effort proves worthwhile; in this sequence, you can see the shift:

This is Aisha’s faith rewarded, which is something she needed, since her own mother cut her off for being engaged to a non-Muslim. Aisha needed someone she could rely on and trust.

That’s why all that comes after this moment is so deeply horrible.

The ghosts of the dead come out in full force at Aisha and her family. Invisible, they hold Aisha down, tormenting her as Leslie and Kris watch, unable to grasp what is happening. And as Kris approaches, the ghosts seize Aisha’s arm so that she strikes the child's face. This is not their first attempt at framing Aisha as an out-of-control monster who cannot be trusted. But Leslie believes in Aisha's humanity, even amidst that horror, which leads to one of the darkest turns in the story.

The ghosts opt for a different strategy. They attack through Aisha so that Leslie and Kris fall down a flight of stairs, with Kris ending up in a coma, and Leslie dead. Aisha, as she’s begging for help, pleading for an ambulance to be called for her family, is dragged away by the ghosts and placed outside the complex. And as all of them end up in the hospital, the expected happens.

A White woman named Haley says she saw Aisha, an "Arab," deliberately push her family in cold blood. A journalist tries to get another one of the residents to connect this incident with the prior bombing, because both involve Brown Muslims. Aisha, bedridden, on the verge of death, is blamed for the whole thing, narrativized as a crazy Muslim.

This is what the ghosts in the house were aiming for, because they are a horror genre manifestation of a very real monster: a system that reduces any and all individuals to the most convenient racist narrative - that quite literally imprisons them within their assigned framing. It matters not that Aisha isn’t Arab, she’ll still be assigned all the connotations of one; everyone who isn’t White is reduced to a horrible internal bias. It’s the blatant nature of post-9/11 America and western thinking on loud display.

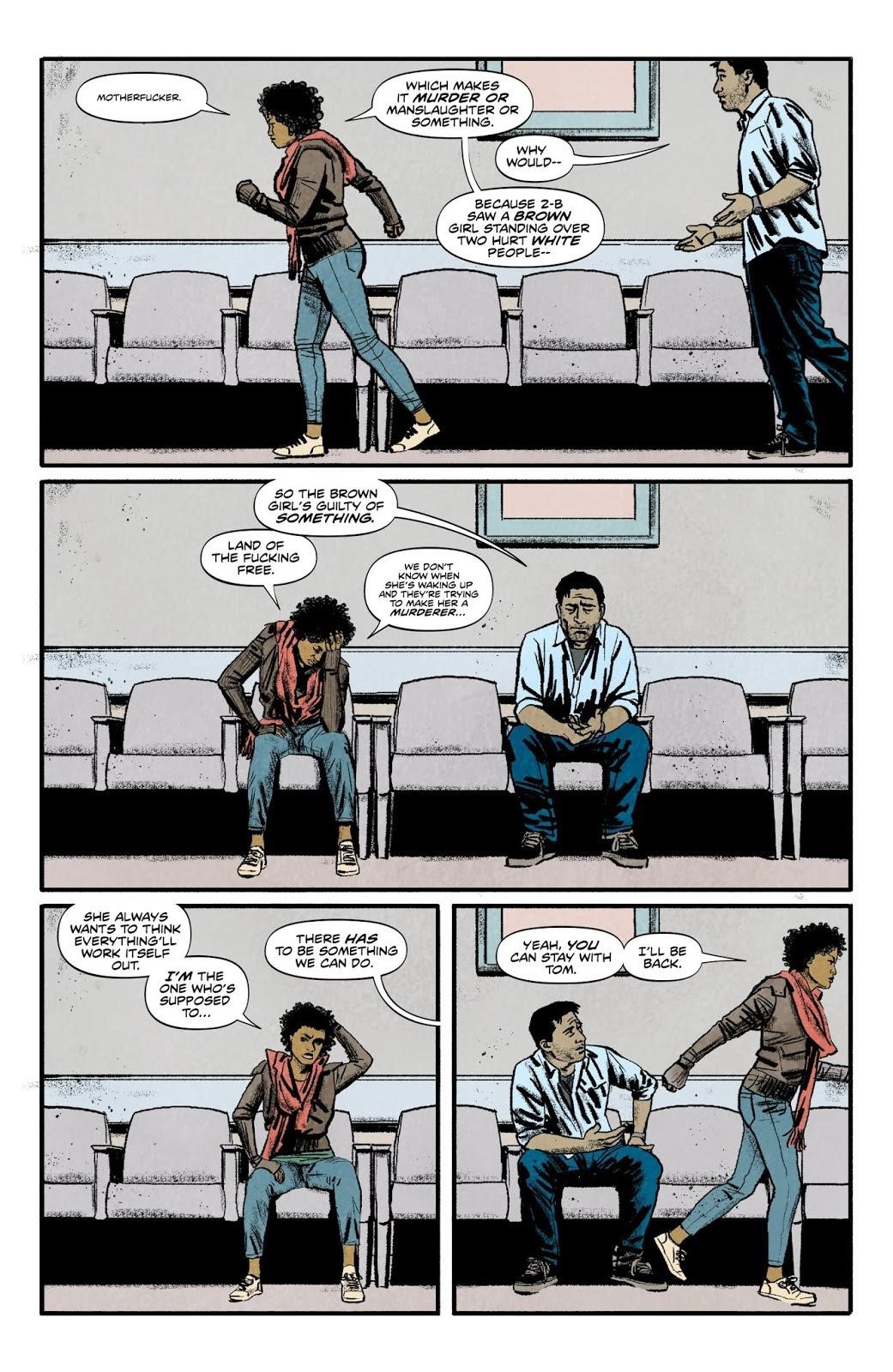

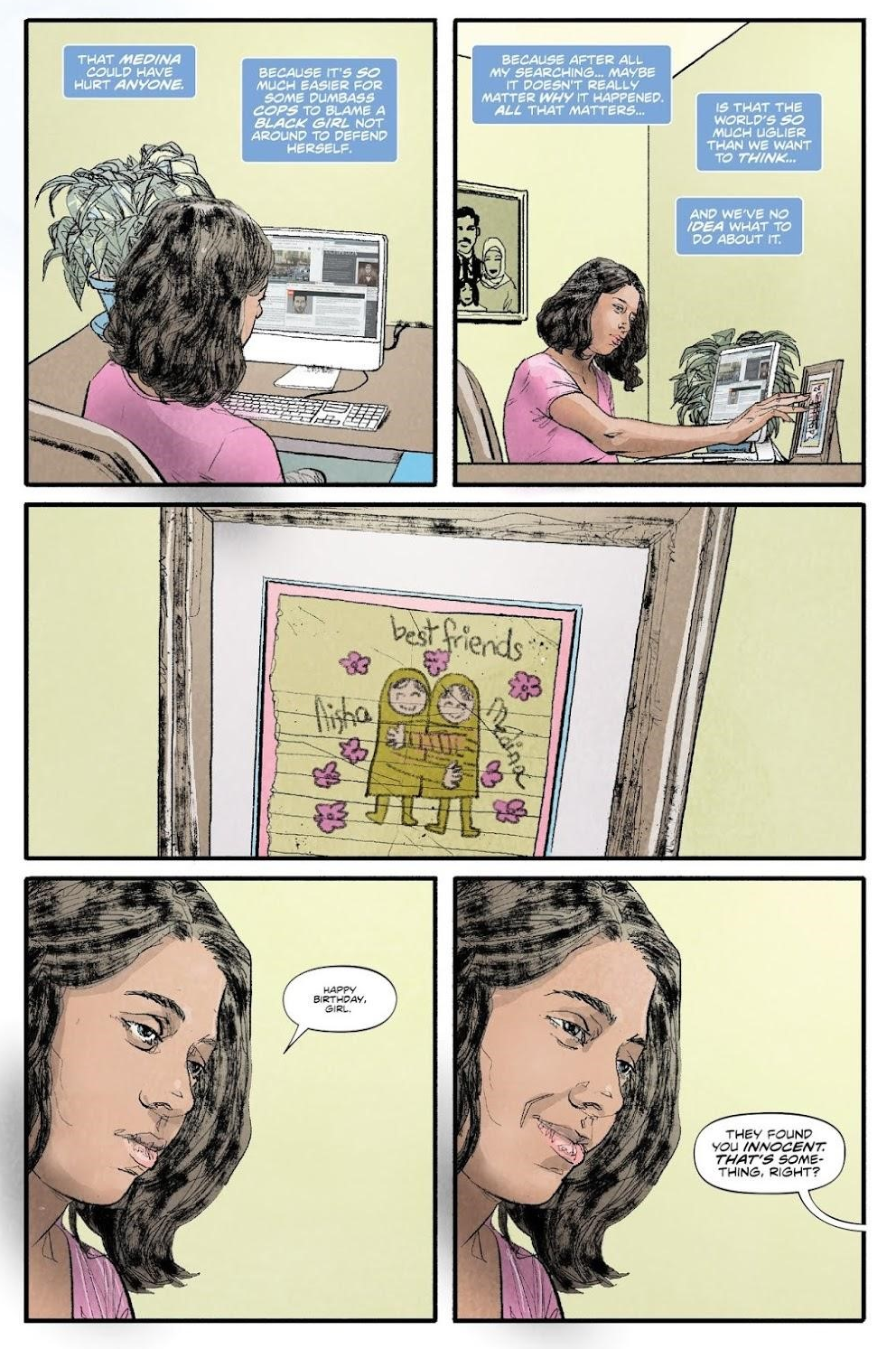

This incident shifts the weight of the book in its second half squarely onto our other lead, Medina, who must then fight for Aisha. For if Medina doesn’t, who else will?

In Infidel, the staple horror device by which some characters can see the ghosts, while characters cannot, is a key idea carrying massive implications. The ghosts seem to primarily be visible to BIPOC. But also, just because you’re BIPOC doesn’t mean you can see them, either. And sometimes, even those who are White can catch a glimpse, if they really try. So what determines who can see this invisible force? We are given a variety of potential in-story explanations for the ghosts of the dead, deliberately contradictory, but there’s something quite distressingly real here... an unseen force of terror that feels like it’s everywhere, but you can’t point to it, so you can’t make visible that horrible feeling you have in the pit of your stomach. Not everyone around you might sense it or understand.

It’s the ghastly nature of bigotry turned into monsters in a horror story: that which both haunts our collective consciousness and lurks amidst our collective unconscious.

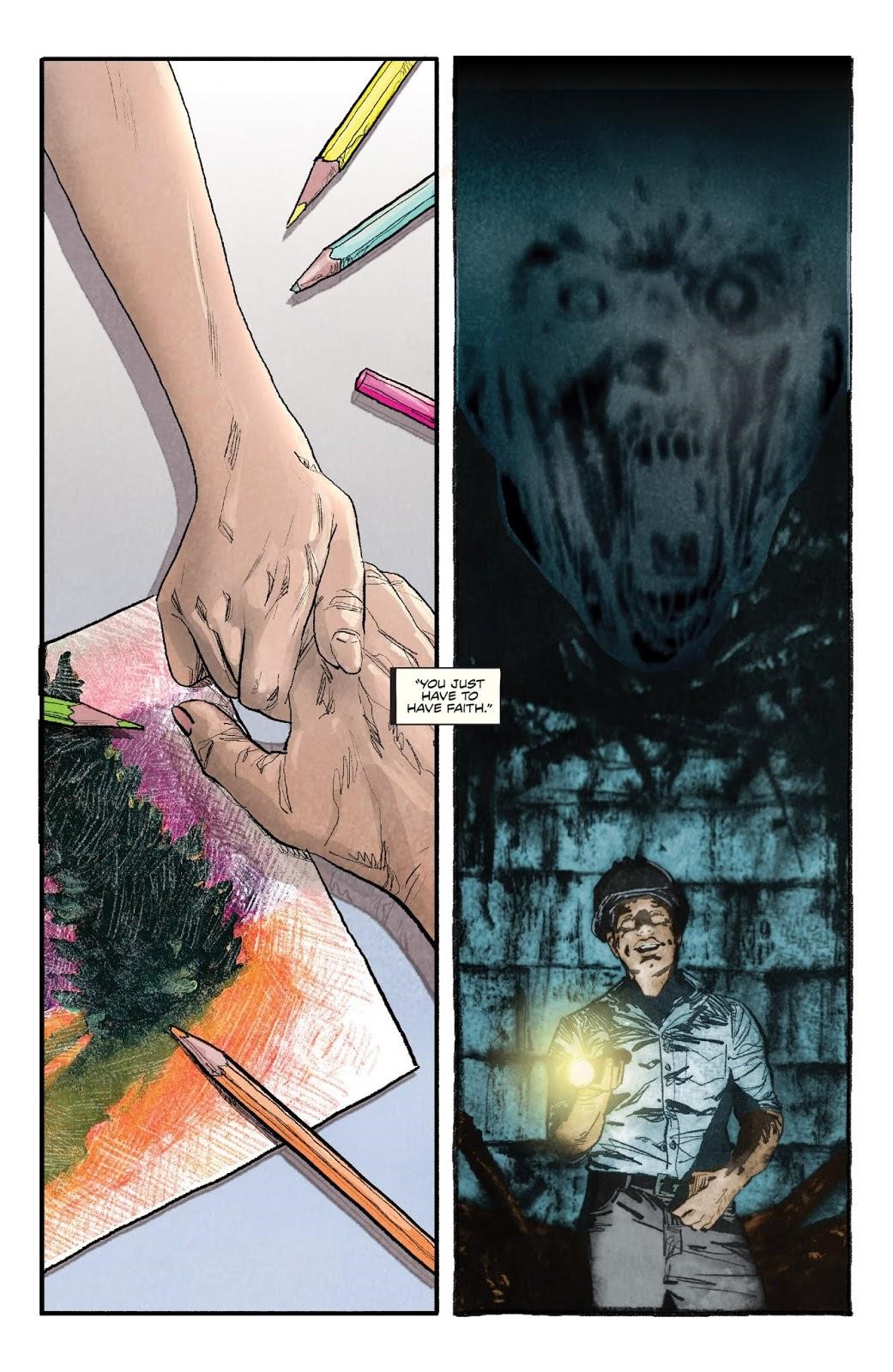

You may notice that the ghosts are depicted in a rather curious and striking manner. They contrast strongly against everything else in the book, because Campbell draws the characters and their world with digital tools, while realizing the ghosts via analog methods. That gives the ghosts a raw physicality, a sense of tactile ‘reality’ that seems to surpass even the characters at points, whilst also visually underlining the contrast of the living and the dead. It’s incredibly impactful. But also, vitally, the scariest moments within the book don't foreground the ghosts. It’s not the astonishingly impactful splashes or spreads that Campbell/Villarrubia pull off.

Instead, it's moments like this:

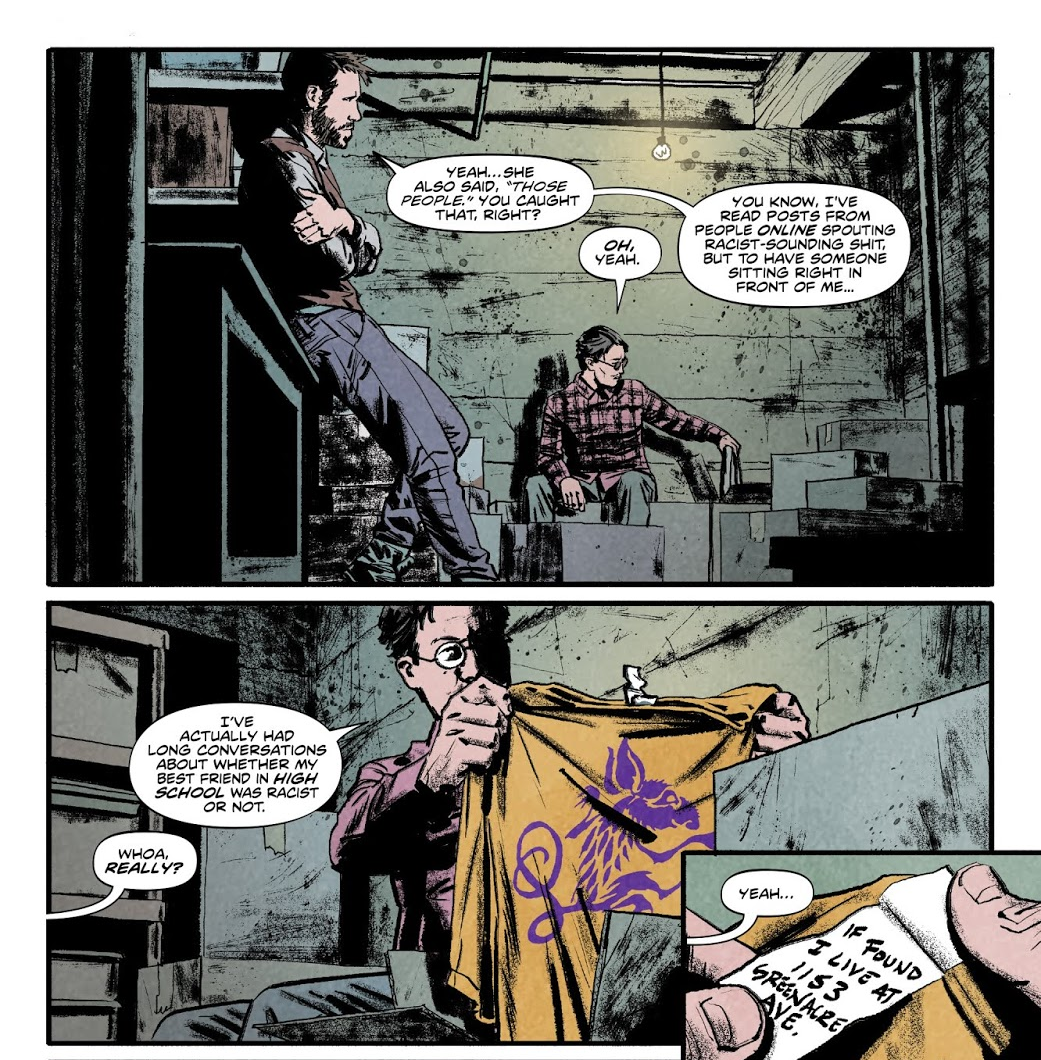

Here we see Grace, a fellow neighbor, an Asian-American woman, just doubling down on how she absolutely thinks Aisha pushed an old woman and a child down the stairs on purpose. And as for Ahmad Shahzad? Grace will not give the benefit of the doubt to "those people." Never mind the fact that being Pakistani-American and Arab-American are two very different things and distinct experiences. None of that matters. Brown? Muslim? Killer.

There’s something deeply, profoundly real here. That distressing, depressing moment—the moment that deflates you—when the friend you otherwise believed you were safe with espouses rhetoric that wrecks your sense of security. Suddenly nothing’s okay anymore. Lines have been drawn; you cannot talk them out of it. The pain of that, the chilling nature of the insidious, creeping poison of that, is at the heart of the fear in Infidel. That when the chips are down, this is what will happen, and those of us with more melanin are fucked beyond belief.

It’s also why it matters here that Grace isn’t another White woman. She’s Asian-American, like Pichetshote, the comic's writer. She has experienced racism and known it. But that doesn’t mean she cannot be racist towards other marginalized groups. That’s why the she argues that Brown people get the benefit of the doubt when White people do not. It’s horrifying, yes; it's racist horseshit, yes. It all stings, to be sure. But we see it all the time.

Grace cannot see the ghosts. Grace is possessed by that which she cannot see; she will insist that what she cannot see doesn’t exist, that she isn’t racist. To even begin to catch a glimpse of the ghosts, to truly be able to see what is there, requires an openness and consideration of one’s own biases and beliefs. An understanding and perspective of race and oppression that is asking questions of not just the world and the narratives around us, but ourselves.

This brings us to the heart of the text.

Race is, above all else, a social construct. It is an idea, not a fact, as the historian Nell Irvin Painter put it. Let us consider that for a moment. ‘Construct’ is the key bit there: something built, something that exists in social context the way it does because it was made to do so. Not a fact of biology, but an idea by which to understand a people. And at the center of the idea of race, always, is the idea of Whiteness.

Race is always defined and measured in relation to White people and Whiteness, an abstract category that once excluded Italians, Jews and Irish, but now includes them. It is the category of convenience which can be extended or pulled back to serve the powers that be. It is the sun around which all other racial categories and understandings orbit. Consider in this context a term we see often: the marginalized. It means, quite literally, to be on the margins due to an external force. The external force here is Whiteness, which is upheld as neutral, eternally central, against which all else is defined. Whiteness—and this is the real power of it all—operates invisibly.

Consider how many times you’ve seen a racial category mentioned in writing. Now, consider how many times you even see White capitalized like the rest of them. More often than not, it’s always white, not White. It doesn’t draw attention to itself. It just sits there, uncapitalized, buried, unassuming. That’s very much why every single White terrorist or shooter can get intense coverage and people digging deep for their humanity, often at the price of their very real victims and their loved ones, whereas you put a Black or Brown person there, and the judgement is swift. To be White is to have interiority, to have the capacity for nuance. Whereas to not be White is to then be something else entirely, defined not by humanity but its absence.

I recall once describing Whiteness to a White friend of mine as an impossible mist. All all-pervading, ever-oppressive mist which most (White) people can’t even see, though they can breathe just fine while under it. But it is a mist under which all others, all deemed as deviations from the humanity or normalcy of Whiteness, suffer. Something so visible to so many of us, but so utterly invisible to many of whom who help perpetuate it, which is by design. The very existence or presence of it will be vigorously denied, even as we all fall on our knees and cry out for breath.

Scarier still is that the mist convinces those coughing and suffering for breath, that the cause of their suffering isn’t the mist, but the others choking alongside them. It fundamentally divides people and sets them against each other, turning the oppressed into the oppressor of others. It’s how you get people doing Oppression Olympics and ruining one another. The blame and focus is put on anyone and anything except the mist which is killing us all, and the ever-promised and dangled carrot of ascendancy is that of the privileges akin to Whiteness, whereby you don’t choke, but breathe free, standing tall above all others. Free at last.

The White mist promises the oppressed that they will finally be loved by their oppressor, if they juuust do this one thing. And then another. And another. Ad nauseum. Ad infinitum. It possesses people, blinds them, and keeps them locked in their distorted view of reality, pursuing a liberation that will never come.

Bind with the White hegemony, and it’ll take care of you real nice. This is the fallacy that is fed to people, which helps it maintain its eternal power.

All of this is incredibly relevant to a work like Infidel. What is it like to reckon with racist evils which many cannot even begin to see? That’s what the book takes and weaves into an intricate horror story. That which hides in plain sight and haunts us all, all the time, suffocating us, which we can’t even begin to explain to others. What is it like to deal with that?

-Derrick Bell, in conversation with David R. Jones on The Urban Agenda, 1994

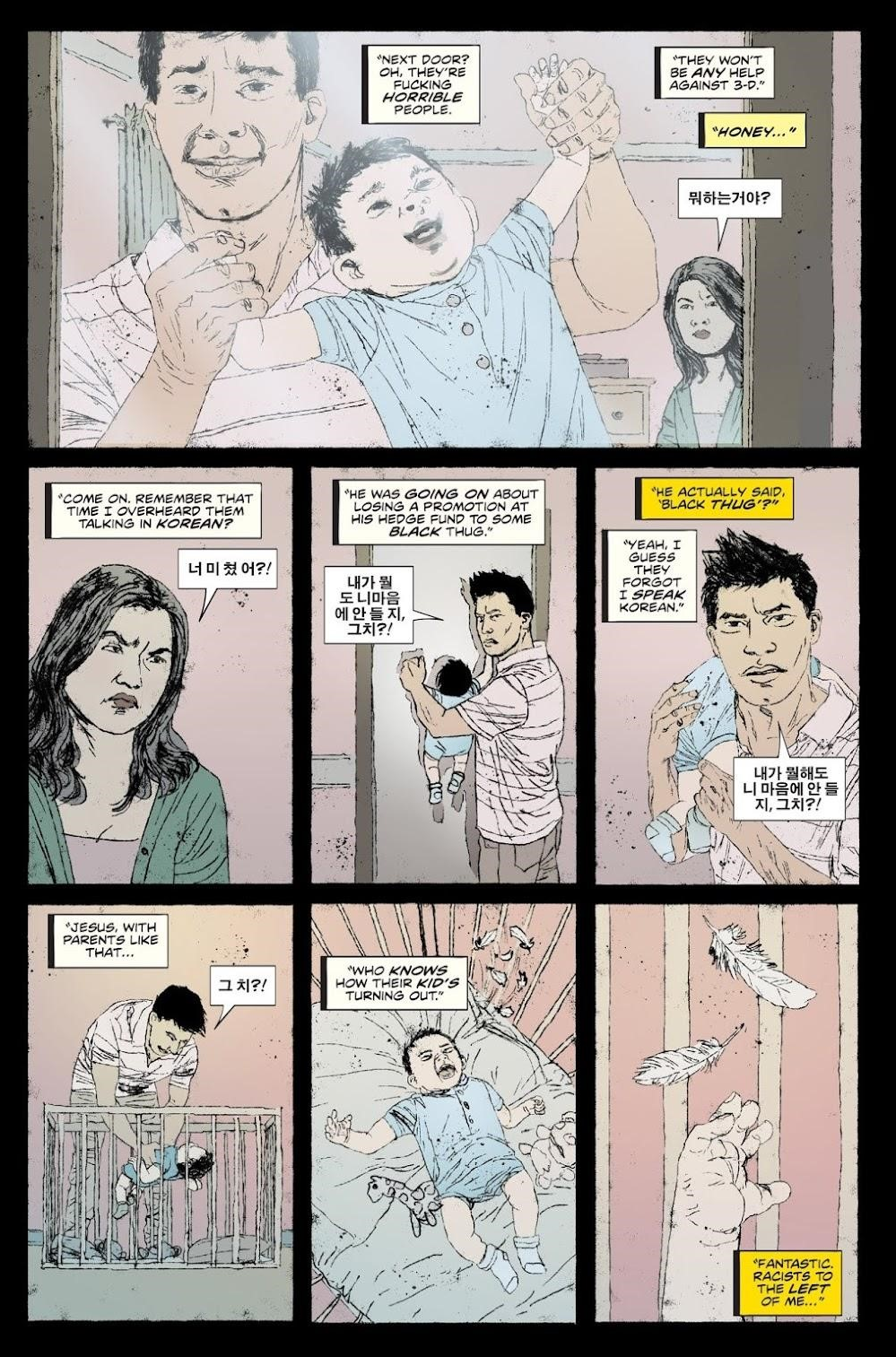

It’s crucial here to emphasize that the ghosts of the dead are not just racist White people. It also includes the Korean family, the father of which describes his colleague as a "Black thug," which should not go unnoticed. It’s partly why the dehumanizing benign racism of viewing BIPOC through a conveniently idealized lens is useless. It’s why the model minority myth, strongly bound to Asians in western spaces, is utterly pointless, and only a tool to serve the status quo. That marginalized people can be wrong, flawed, and played against one another—that they too are human and are happy to join the human machine of exploitation for profit—is key. It’s how any demographic is pitted and played against the other as needs arise, to secure votes and support.

Note the rhetoric above. Black thug. Where does that come from? Where does it emerge from - this racist idea that all Black people are criminals? How did it come to exist? It exists because of the White hegemony perpetuated this idea far and wide, until to many it became ingrained reality. Here, the couple has decided to bind with White hegemony, despite their own oppression, and it’s why it’s no surprise that even as ghosts, they are bound as empty husks of bigotry and hatred alongside their fellow White racist peers.

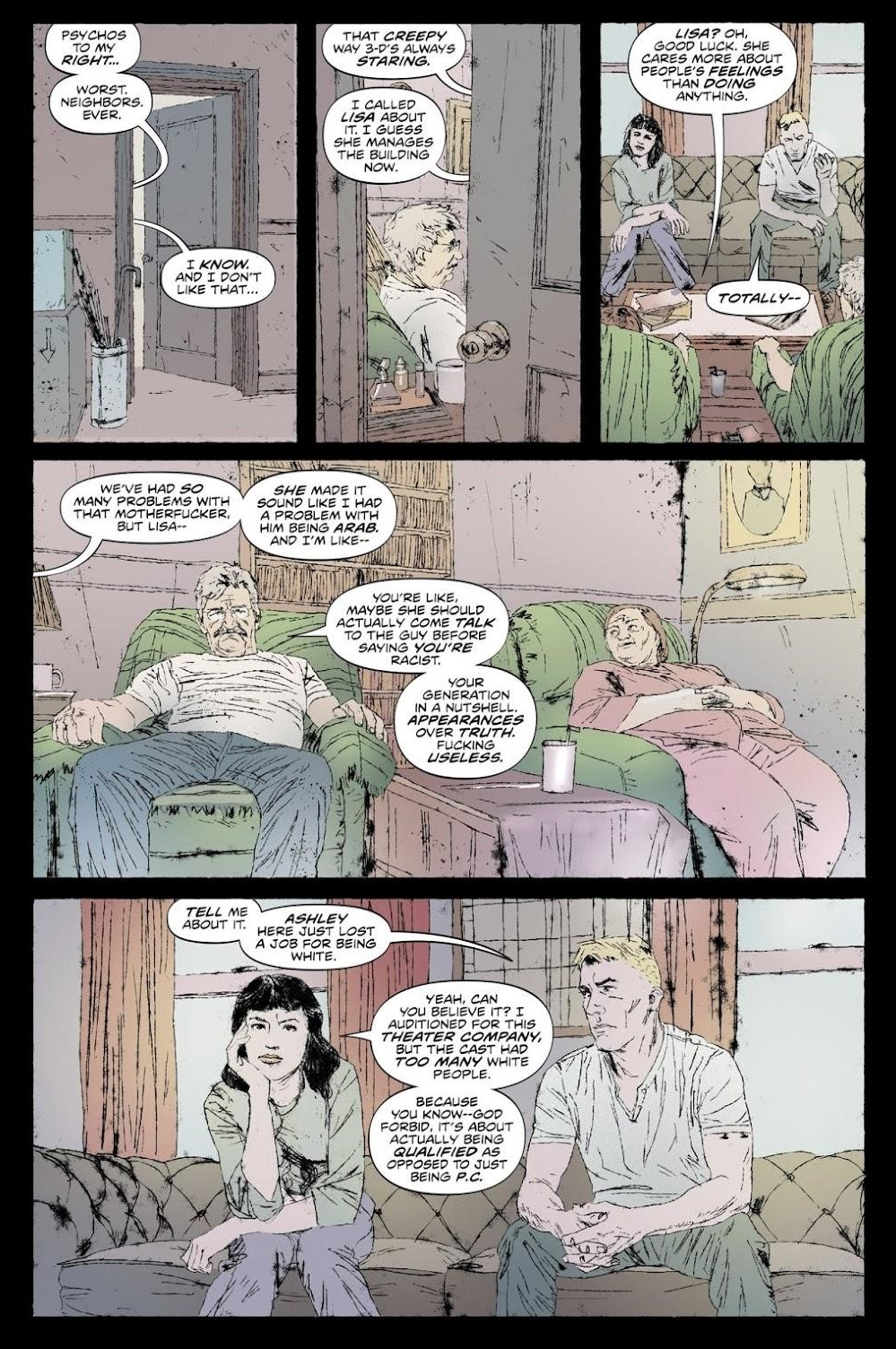

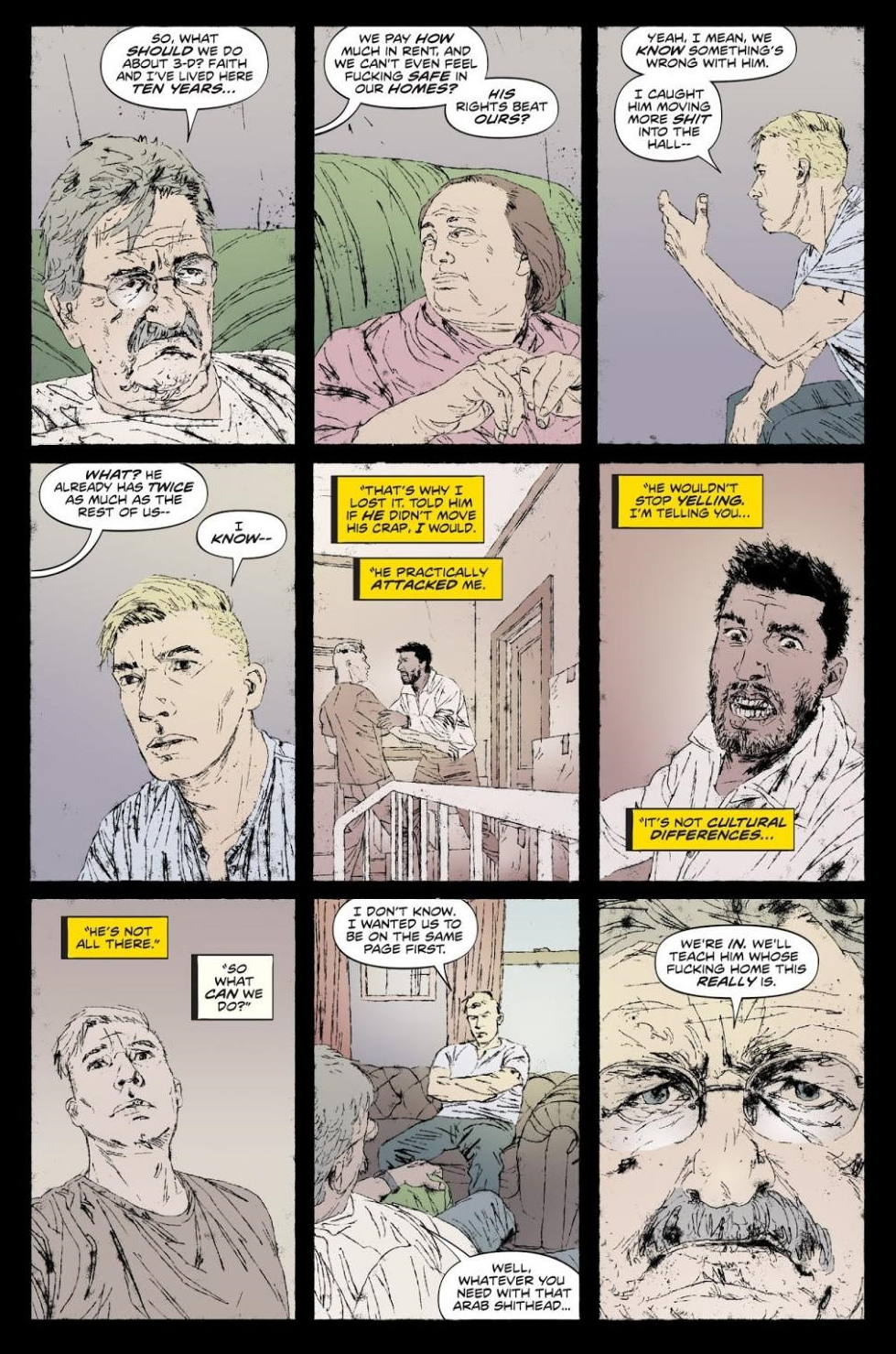

Infidel understands very clearly that racism is ordinary. It is banal and regular, for such is the nature of evil. It is why we’re shown scenes of the people the ghosts once were, and we’re given a sense of its nature in life. We see the ordinary, everyday racism in the White actor and their partner venting about not getting a role because they’re White. That things are too P.C. now. We see it in the elderly White professor trying to justify slavery and how it was necessary for America to become a great nation. It is, after all, the collective accumulation of such banal evil that creates the tyrannical systems that prevent progress.

The terror of the invisible standard, the normative society within which White neutrality is presupposed, is what Infidel addresses. None of the assumptions or leaps made about Black and Brown people by characters in the story would get made about White people. The further away from 'White' you are, the more likely your monstrosity is. Grace, the trusted friend, would never look at a White terrorist, raised Christian, and assume all White people are terrorists. But she looks at Ahmad Shahzad and assumes that of Brown Muslims, because that’s what she’s been conditioned into believing. Haley, the woman who claims to have seen Aisha commit murder, would not leap so fast to judgements had Aisha been White. But she does, because Aisha is not.

Ahmad Shahzad may have made those explosives, much like any White man named John might have, for violence is not new and not exclusive to any group of people. That one violent person existed at one point in the past doesn’t mean the people they belong to are all inherently violent savages. It does not mean anyone who shares their skin color is a cold-blooded inhuman individual. But Grace assumes this, and so does Haley.

All the ghosts of the dead, which are just ideas given form, expose the nature of the systems amidst which people and ideas of race exist. It is, after all, from that very system of assumptions that they are born, these hateful ideas, which now haunt the place.

As the story progresses, Ethan, Medina’s roommate, suffers a brutal fate while investigating the connection between the ghosts and this world: "things here that could be possessed by the other side's darkest entities," as one character posits. The same fate befalls Tom’s close friend Sendhil, an Indian man, who is possessed to strangle Ethan before falling dead. And who gets blamed for it but the Black woman, Medina, who enters the scene next - because of course! She’s even Muslim!

In every situation, the ghosts of the dead have tried to reduce the humanity of women, turning them into hollow racist constructs, until they’ve succeeded. They failed with Leslie, so they leaped to Haley, which fanned the flames that spread to others, like Grace. Thus inevitably, they attempt to do the same with Medina. It was bound to happen.

The trope of the innocent individual(s) seen crouching over dead bodies and blamed for the crime is another one that is old as time. And, as with the device of seeing the ghosts, its use here is quite charged, loaded with implications when used in conjunction with the narrative at play. The assumptions one makes about the other in seeing them acquires whole new narrative weight and meaning in this context of examining race.

At the end of the story, Tom, Aisha’s partner, becomes the prime agent of the antagonistic force, possessed by the same poisonous rhetoric that feeds and fuels the ghosts. He blames Medina for all his misfortunes and suffering, reducing her to his assigned narrative construct: the role of traitor, which erases Medina's suffering to foreground his own. He forgets that Aisha is someone Medina would die for; someone Medina has stuck by and taken care of her entire life, before Tom even entered it. But Medina’s suffering is invisible to him.

It’s a striking twist upon the initial expectation of Leslie being the antagonist figure. The old mother-in-law, for all her flaws, is able to catch a glimpse of the ghosts, which Tom, her supposedly progressive son, who complains so much about his mother's xenophobia, never does. This is because, once again, Leslie is actively accepting the ordinary nature of her racism and is trying to correct it, trying to unlearn and do better, while Tom is too busy caught in his own pain. He never realizes how his suffering and anger are being manipulated, the way it is in the real world against marginalized groups. They could be your friends or family, it doesn’t matter, the finger will be pointed at them - and, in their pain, the gullible will buy it. It’s why Tom is full-on ready to believe the Black woman is the culprit behind everything, even though proper consideration would lay bare how ludicrous that is. It’s easy for him to just give in to that impulse, feeling justified in his actions.

And thus we get horrific sequences like this, as the price of White rage and White catharsis becomes Black pain and tears. This is what the system does. This is what it was designed to do.

That’s the thing to understand, isn’t it? Ghosts manifest, and are conjured, for a reason. These things are just symptoms of a viral idea, a cultural disease that exists not just physically, but mentally and spiritually. The image of the ghost whispering in the ear of the haunted might as well be indicative of every forgettable Fox News scumbag or rightwing pundit whispering poisonous horseshit into the ears of people.

The end of Infidel is devastating. Medina, who’s endured horrible cruelties, beating, torture, who’s lost her roommate, her best friend, accused of murder, manages to stand back up. She did not have to suffer to this extent, but earlier in the story she has seen the bedridden Aisha scream from the presence of the ghosts of the dead, and if she flees, Aisha is certainly doomed. Thus, for the sake of her friend’s life, she sets off a second explosion, sacrificing her own life to cleanse the complex.

Aisha wakes up. Leslie is dead. Tom is dead. Sendhil is dead. Ethan is dead. Medina is dead. And she’s still here.

She was found not guilty of killing Leslie, of course. But it cost her a fortune to get a lawyer who could make that happen, which had to be paid by her mother, who once cut her off, but arrived immediately to save her daughter from a system set up against her. It took Aisha’s mother mortgaging their house. And more importantly: she was found not guilty because now the system has a better scapegoat. A Black woman, who was a Muslim, who set off an explosion in the same place where another Muslim was blamed for another explosion. The entire narrative could be shifted onto Medina, to free Aisha.

That’s the nature of White hegemony and White-centric conceptions of race, isn’t it? They require blood sacrifice to maintain their relevance.

But Medina probably knew that. She knew that impossible cost, and made the sacrifice anyway. The truth will not actually matter, it will never be known. All that will exist, and persist, is another case file in the library of the Other: something farther away from the humanity of White people.

It’s a harsh, brutal conclusion. It hurts. It’s depressing. But it also feels incredibly real. There’s a weight to it. A truth and an honesty that hits hard. This is no ‘Aaand we beat Racism, guys!!’ genre story like many a White creator has published. This is informed by reality and tempered with truth.

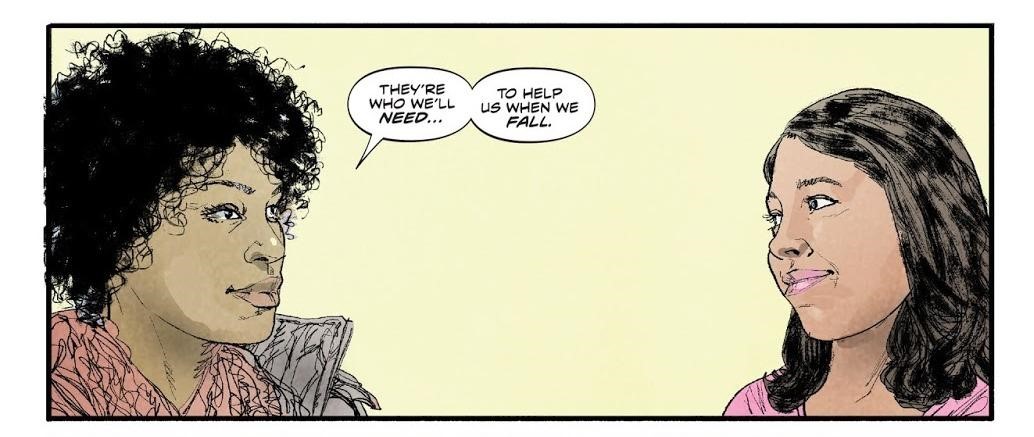

Which is perhaps also why the work seeks to offer some solace, whilst acknowledging the deeply fucked up nature of these systems that birth the horrors we’re haunted by. It despairs of things as they are, but it also expresses, once more, that you cannot just give up. You cannot just lay down and believe it’s all over. You have to be able to believe in the better. Sure, the system is monstrous, but individual people, like Leslie, can indeed change. That the majority cannot and will not does not mean it’s the end. Everything must begin on some level, however small.

We cannot live life without love, without trust, without faith, for that is no life at all. We need those things, as well as the faith that things, on some level, however small, can be better in some form. For if those that came before us did not believe in that possibility, if they had given up, we wouldn’t be here standing atop their efforts. We owe it to them to believe in the possibility of change, of betterment.

The ghosts, the monsters, like the systems that produce them, will always exist. They’ll always endure. They were designed to. All we can do in the face of that is muster up our own strength and be resilient. For only then can there be salvation. Only then might we ever be free of our shackles, clear of the mist, our ghosts exorcised.

It is a future worth dreaming about.

The post <em>Infidel</em>: The Terror of White Neutrality appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment