I'll readily admit this much: until I opened the book, I'd never heard of most of the dozens of creators featured in A Very British Affair: The Best of Classic Romance Comics. Like its subject, British romance comics of the 1950s through the 1970s, many of these talents have largely been forgotten, with only a precious few kept visible in UK comics circles by shifting into the neo-pulps and sci-fi serials of 2000 AD and its contemporaries.

It's hard to believe the scope of such collective amnesia; the romance comics of Britain were immensely successful at the time, producing thousands on thousands of original pages and selling millions of copies - numbers which, in the view of what has been archived in print, do not amount to much at all. Part of this, one might hazard a guess, is because British comics are even more of a perceived "boys' club" than their American counterparts; girls' stories belonged to the girls, and were all too eagerly dismissed.

Impressively, this collection appears to be the first of its kind; many of these stories have never been reprinted since their original publication, and a not-insubstantial number of pages come from curator David Roach's own collection. By putting a spotlight on this genre, Roach and editor Olivia Hicks attempt to rewrite the common narrative of the Anglosphere by showcasing the women, on the page and working upon it, that played a significant role in its makeup. Names like Jenny Butterworth (one of few scriptwriters credited here) and Purita Campos are perhaps not the first to be uttered in most histories of the British comic, but that certainly doesn't discount the impact they've had. Across 200+ overloaded pages, this collection displays as vivid a picture as one can hope to achieve of a genre willfully neglected - as well as some potential reasons it has not survived.

One major problem, shared by many of the pieces in this collection, emerges through no fault of their own. Classic British comics—arguably more than those from any other geographical sphere—are defined by brevity. The British magazine format traditionally afforded its features only two to five pages, often leaving them to feel more like the recap of a story than a story in its own right, relying on a "call-and-response" rhythm wherein the text narration drives the plot forward while on-panel depictions serve as illustration more than action of its own accord. Here, this breathless mode of pacing is constantly at odds with the innately mannered nature of the text, undermining emotional urgency; the impact of romantic love is dulled by overwrought histrionics and the relative flatness of the characters. More often than not, lovers are reduced to ciphers and archetypes, defined only by their relation to one another, becoming more-or-less interchangeable in their interiority; only their external circumstances set them apart, at least nominally, from one another.

As is often the case in such collections, the most interesting stories in A Very British Affair are the ones that fail to be contained by such editorial constraints and expectations. A good example is the Shirley Bellwood-drawn "Ann and Pam" (1963), whose lean, streamlined structure defies everything that came before it. Told in just eight panels—about a quarter as many as one would expect, even under such constraints—the story seems to acknowledge the impossibility of depth, choosing instead to depict its core romance only in its nascent first steps, ending right when the protagonist meets her suitor. Where other stories attempt an arc, "Ann and Pam" leaves only an implication, a potentiality - and is much more compelling for its omissions. Noteworthy too is "This Is It" by Butterworth and Mike Hubbard (1961), one of the only serialized stories compiled in this book. Telling the story of Merle and her boyfriend, George, who is all too eager to squander good will and opportunity, the multi-chapter structure affords the characters' romance a complexity that is sorely absent from most other pieces, as we can see Merle's despair grow, and George's opportunities repeatedly turned away, over whole chapters instead of five panels.

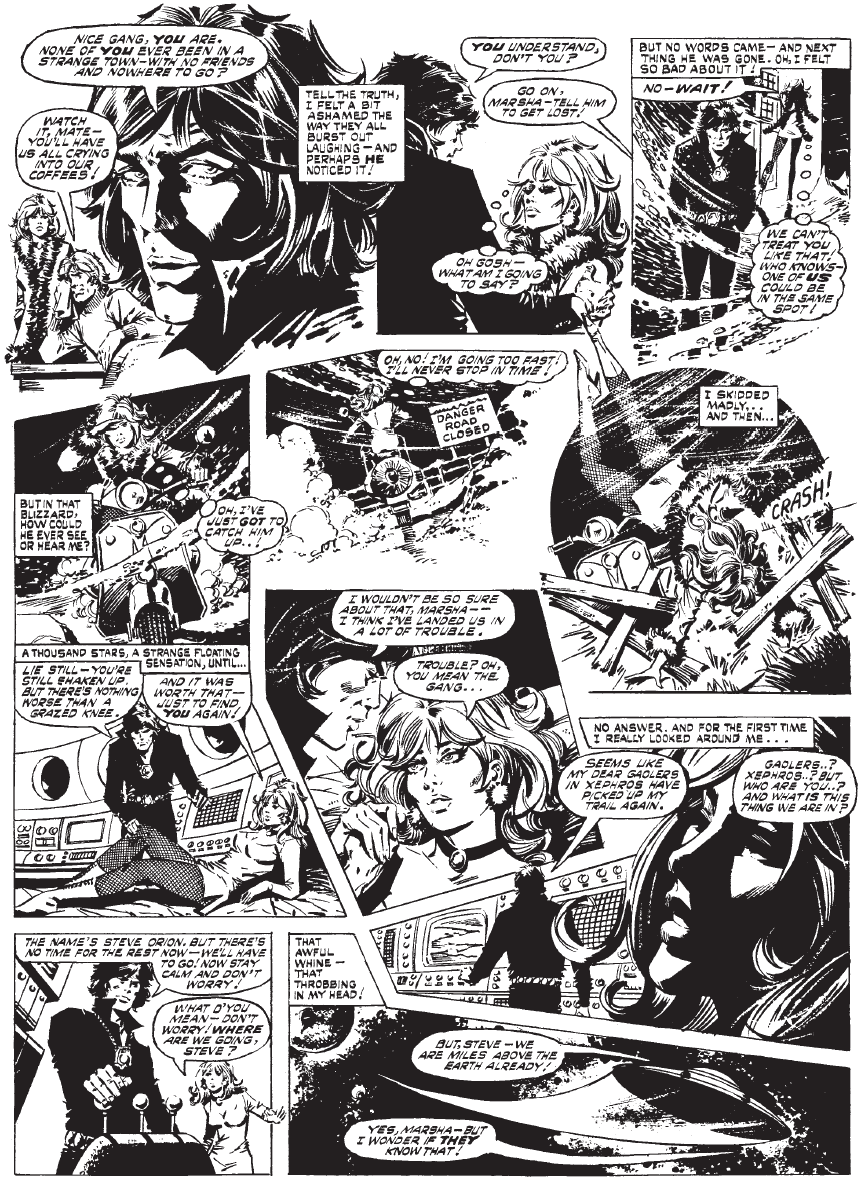

But the overwhelming impression of love in this collection is less that of an emotion than an all-powerful ubiquitous force that warps everything it encounters. In some cases, this is written off as a taming of sorts, as with the Jordi Longarón-drawn "Love? Not for Me!" (1963), in which a man starts off sneering at what he frames as the all-powerful nature of the feminine marital impulse, only to find his own lover who convinces him to get married. Later stories betray a sort of narrative restlessness, trading the mod-Brit aesthetic for a speculative fiction sheen; Enrique Badía Romero's "Prisoner of Xephros" (1973) shows an alien, the delightfully-named Steve Orion, escaping a space prison and quickly finding himself in a relationship with an Earth girl.

Other stories attempt a different tonality, only to find themselves right where they started. In the Manfred Sommer-drawn "Living Doll" (1964), a woman and her boorish partner attend a farcical puppet show about a girl incapable of leaving a clearly-abusive boy; the woman sees too much of herself in the play. It makes for a stark contrast with the preceding stories, as this is the first time a man has been framed as worse than a flake or a prick with a heart of gold, but the fourth and final page of the piece ties it back to the overwhelming pattern of the book as the protagonist leaves the show in discomfort and immediately finds a new and better partner. Through Roach's and Hicks' curatorial framing, love in classic British romance comics takes on an almost Kierkegaardian character: where momentary doubt exists, it is ultimately to reinforce and preserve a higher, more absolute faith.

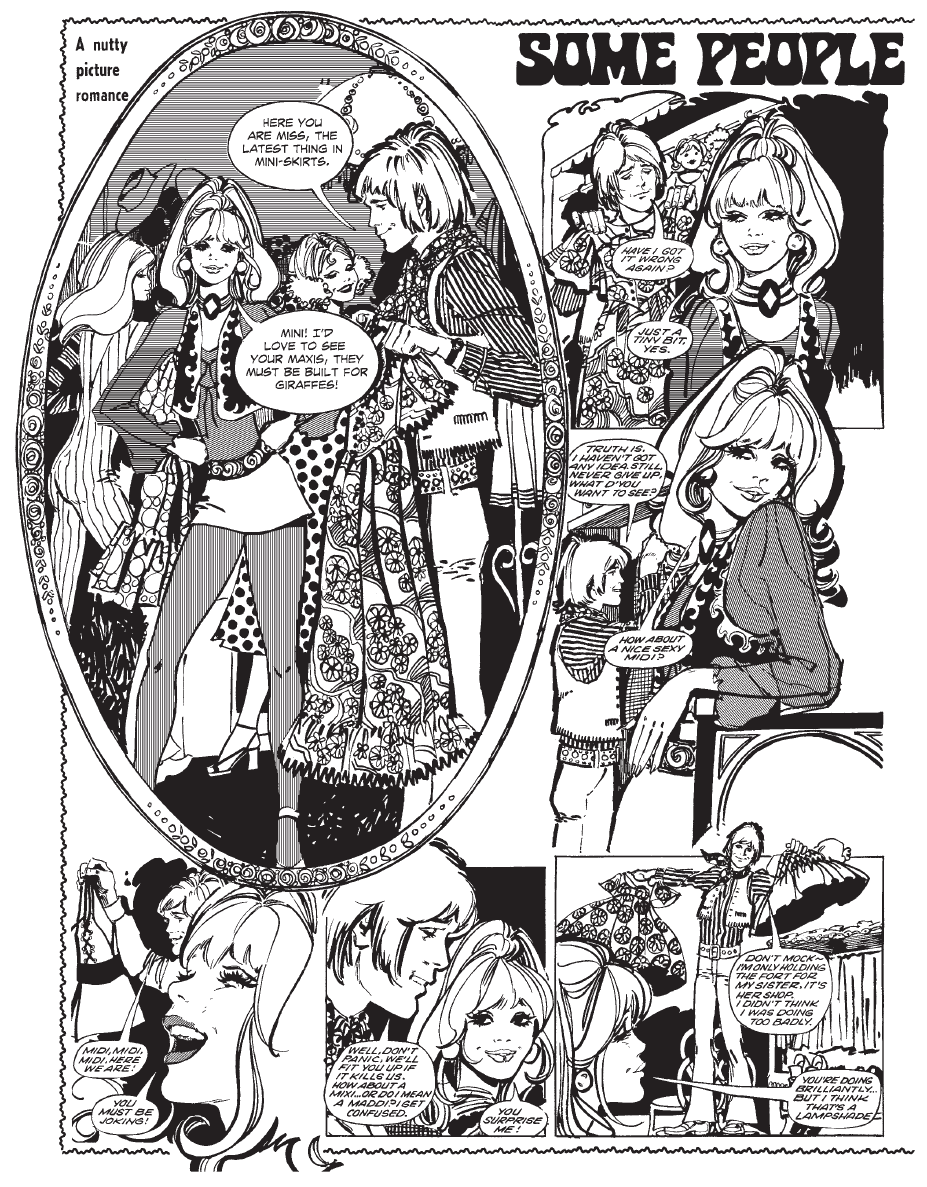

Of course, the density of the scripts also results in visual clutter; dialogue and expository narration take up as much weight as the characters and environments depicted. It's an extreme constraint, leaving the artists very little space, physically, to draw on; some of these pages are broken into a dozen panels at a time. The result is a unified visual/aesthetic front that prioritizes character art, with background environments and set pieces reduced to their bare essentials, bringing an almost theatrical sparsity to the drama. Compositions are tight and frenetic in their effort to focus on characters without repeating angles. Texture too is often kept to a minimum, with surfaces left blank white more often than they are rendered, giving many of the characters and objects the appearance of floating. There are some stories, especially in the beginning, that attempt a more realistic approach, rendered in watercolor and ink wash to evoke a photo novel vibe, but those only heighten the stiffness of the writing. Indeed, it's the more stylized cartooning that shines through, often with rich, slightly-scratchy inks (presumably a necessity given often-shabby printing conditions): artists like Longarón or Vicente Roso ("When Love is Masked", 1962) are memorable despite stale scripting and tight panel layouts, while later pieces, such as the Purita Campos-drawn "Some People Have Got No Idea!" (1970) and the aforementioned "Prisoner of Xephros", enjoy more license in terms of panel shapes and sizes, amplifying their angularities and directional flow.

The comics in A Very British Affair prop up a world that's all surface - ideal not for reading, but for readers' projection thereon. They appear preoccupied less by romance than the signification thereof. Roach's and Hicks' collection is unlikely to inspire in its audience any overwhelming faith in the power of love—at least not as an emotion that they can recognize in themselves—but it serves as a strikingly well-articulated depiction of the evolution and ossification of a narrative language.

The post A Very British Affair: The Best of Classic Romance Comics appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment