What’s the biggest mistake you’ve ever made in your life? If you could go back in time to undo it, would you? Even knowing it would change everything else - even any potential good that came about as a result?

That’s the question at the heart of G.I.L.T., our subject for the day - but, not to be disingenuous, the book itself wastes no time prevaricating. (That acronym stands for “Guild of Independent Lady Temporalists”, incidentally.) Fixating on the past, on what you could or could not have done different, is unambiguously unhealthy. All that fixation accomplishes is to estrange you from the present. That’s one of those things people either figure out for themselves or suffer the consequences as their life spins out of control.

Of course, your life might spin out of control anyway - you’ll find no guarantees on the matter from this review. Your humble reviewer has made many mistakes in their own life, but I’ve owned them. Like a grown-up does. I put the car in the ditch myself.

And that’s that’s the heart of the matter, right there - growing up. Getting over yourself and realizing the universe will never part the ways to allow you, personally, a do-over. So you should probably stop agonizing about it and trudge forward the best you can.

Except, you know - what if you could? Even a healthy, well-balanced person might be tempted to hurt themselves if given that opportunity.

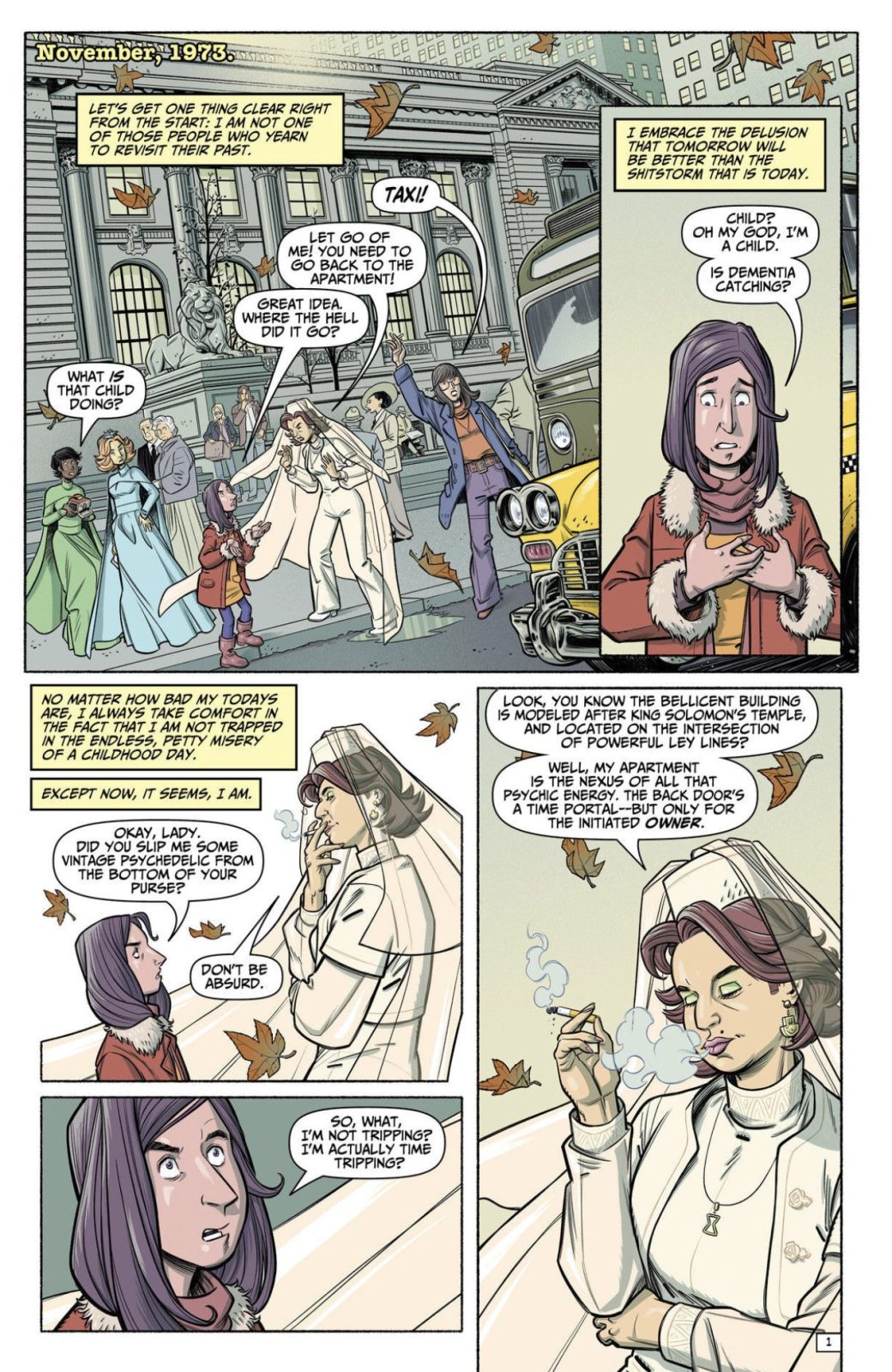

G.I.L.T. is a time travel story, but a very specific kind of time travel - astral projection through a person’s own lifetime. Your mind dislocates from the present and appears in your body 20 or 30 years ago. Supposedly you can’t really change anything on these trips, but you’ve read enough of these things by now. A lot of stories have hung on that irresistible what if you could?, and so too does this. Our heroine, Trista, falls into the machinations of her new home health care client, Hildy. Hildy has a secret, you see: she can do that time travel thing I was just mentioning. It’s a consequence of living in a magic building built by theosophists in 1927. Hildy isn’t supposed to travel with anyone - the building bylaws are pretty solid in that regard. Trista ends up tagging along, however, on a trip from 2017 back to 1973. Once rules are broken, complications begin to pile up.

Hildy thinks things would all have been better if she’d just not married the schnook she married in 1973, so changing that one event has become the driving focus of her later life. She thinks that’s the reason why she never talks to her friends anymore. Well, you know what they say - guilt ain’t just a river in Egypt. Oh, I get it, the title’s a pun. Right, right. Carry on.

Our writer for this adventure is Alisa Kwitney, who (since this is The Comics Journal, after all) you may know primarily as a former editor for Vertigo, who wrote a fair amount for that imprint as well. I still fondly remember a Phantom Stranger one-shot from 1993 that was my first exposure to the art of Guy Davis. She’s been in the game for a while and sets about telling her story with confidence and charm. Charm is often cited as a virtue in the pejorative, but this is a charming story in the most gratifying manner. The plot is solid and intricate (for the most part, but we’ll get to that), the characters carried by clearly-defined motivations. But most pressing, as I said, these are charming characters, witty creatures who manage to be funny without becoming caricatures, appealing but not cloying. Even occasionally selfish. Dorothy Parker stops by for a couple pages somewhere in the middle there, and the old girl fits right in.

Of course, even the most charming script will stumble without the right artist. And that leads us to the real star of the show, and the reason I ever picked up the book in the first place, Mauricet. He’s Belgian, so if you have access to Le Journal de Spirou you probably already know all about him and are shaking your head at the poor, provincial monolinguists who had to wait until he did some Harley Quinn comics. If I told you to read a book called Harley Quinn and Her Gang of Harleys you might - well, actually, you might just take that in stride since this is me we’re talking about, after all. I dearly loved Amanda Conner’s & Jimmy Palmiotti’s long tenure as writers on that character. They succeeded so well that their version of our Maid of Mirth more or less became the character’s de facto status quo, certainly up through the underrated movie from a couple years ago and on to the present day. She didn’t used to be a headliner, but now she is, full stop. They deserve a great deal of credit for that. And of course, again, none of that would have mattered without the right artists.

So, what precisely did G.I.L.T. demand of its artist? Well, in the first place, you’ve got a cast made up largely of women—Strike One!—mostly middle age or older—Strike Two!—interacting in a real urban environment at different times throughout history - Strike Three! We are far outside the strike zone for the vast majority of comic book artists who have ever lived. Just stop a moment to parse the challenge here: not only are the main characters women, but they’re women seen at different points throughout their life. We see Trista first in her early 50s, then we see her when she’s 10. She’s still the same character, with the same facial features and expressions. We meet Hildy first on her wedding day in 1973, and then again in 2017. Same character, more lines on the face. But still completely recognizable.

Now, I know I’m just a gullible critic, easily swayed by shiny objects and well-drawn banisters - but seriously, banisters are hard to draw. You usually need to draw the staircase, too. And just the staircase is enough to make most artists quail. Mauricet gives us the staircase, the taxicab, and even the housecats. You don’t appreciate how much other artists are skating by on charm without doing the work, until you meet the man who knows how to draw the banisters.

G.I.L.T. is such a charming read, I confess to being more than a bit disappointed with how things fall out in the last chapter. Everything holds together remarkably well until the fifth and final chapter, at which point the story sort of dribbles out like air from a balloon. Things are pushed forward to an unsatisfactory conclusion - it’s never a good sign when the characters comment on how pat the resolution seems, and that does indeed occur here. The climax is a co-op board meeting, which can’t help but feel deflating. It’s no sin to set up a story for a sequel, but without a satisfactory ending it almost feels as if the book just ran out of pages. There’s also the small matter of a Pam Am flight diverted from 1973 to 2017, a thread abandoned with Lou Reed on his way to record Berlin - how does the timeline change if he’s not there to record “Oh, Jim”? I’ve got at least one ex who would notice her favorite song missing from the universe. There’s a whole book to be written just about what happened to the passengers on that flight.

If the series ultimately can’t pull all these threads together, that’s perhaps to be expected. There’s a lot on the plate here. One of the major themes that permeates the entire narrative is the failure of feminism over the last 50 years - characters reflecting on the last half-century are amazed to find the same arguments recurring in slightly different permutations. The only thing that really changes are the lies people tell themselves. Hildy’s actions are revealed to be a special kind of self-defeating - as much as she prided herself on being a forward-thinking, liberated woman, she ended up chaining her life to regret over a man. Just like so many of her unreconstructed ancestors. That’s disappointing, of course, but it’s also only human. What resolution the story achieves comes through Hildy’s eyes, as she realizes her fixation on the past was, yes, just the thing keeping her from talking to her friends. See? It all comes around in the end.

The post G.I.L.T. appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment