Until the beginning of last year, I didn't know anything about cartoonist and illustrator George Wylesol. At that time, I received a call from Francesco ‘Ratigher’ D’Erminio–cartoonist and editor at Coconino Press–who asked if I wanted to work on the translation of “an incredible book, it’s crazy, you’ll love it.” Wow, what’s the title, who’s the author? “It’s called 2120, by George Wylesol.” I was already Googling the title and the name, but I only got a couple of results; the book wasn’t out anywhere yet. That job sounded like an interesting challenge. Plus, it had been a while since I'd dove into the work of an artist that was new to me.

In a couple of weeks I received a PDF of a non-definitive version of the book, and I started my translation. It was the kind of work, and the kind of story, that drags you deep into a spiral. In translation, you need to lose yourself alongside the characters, and not only by giving a specific voice to them and understanding the book's specific terms - you must seriously develop the need and the pleasure to find out what the hell is going on and what is going to happen on the next page.

With 2120, George Wylesol creates a story where the reader is in charge. Or at least they would think so. You can decide some of the actions and choices made by the main character; just like in an old video game: you can open doors, enter rooms, and decide whether or not to interact with other characters. Wylesol's art is nonetheless slightly uncomfortable; his pages are all clear lines and flat colors, like a dirty and more Xeroxed-like version of Nick Drnaso.

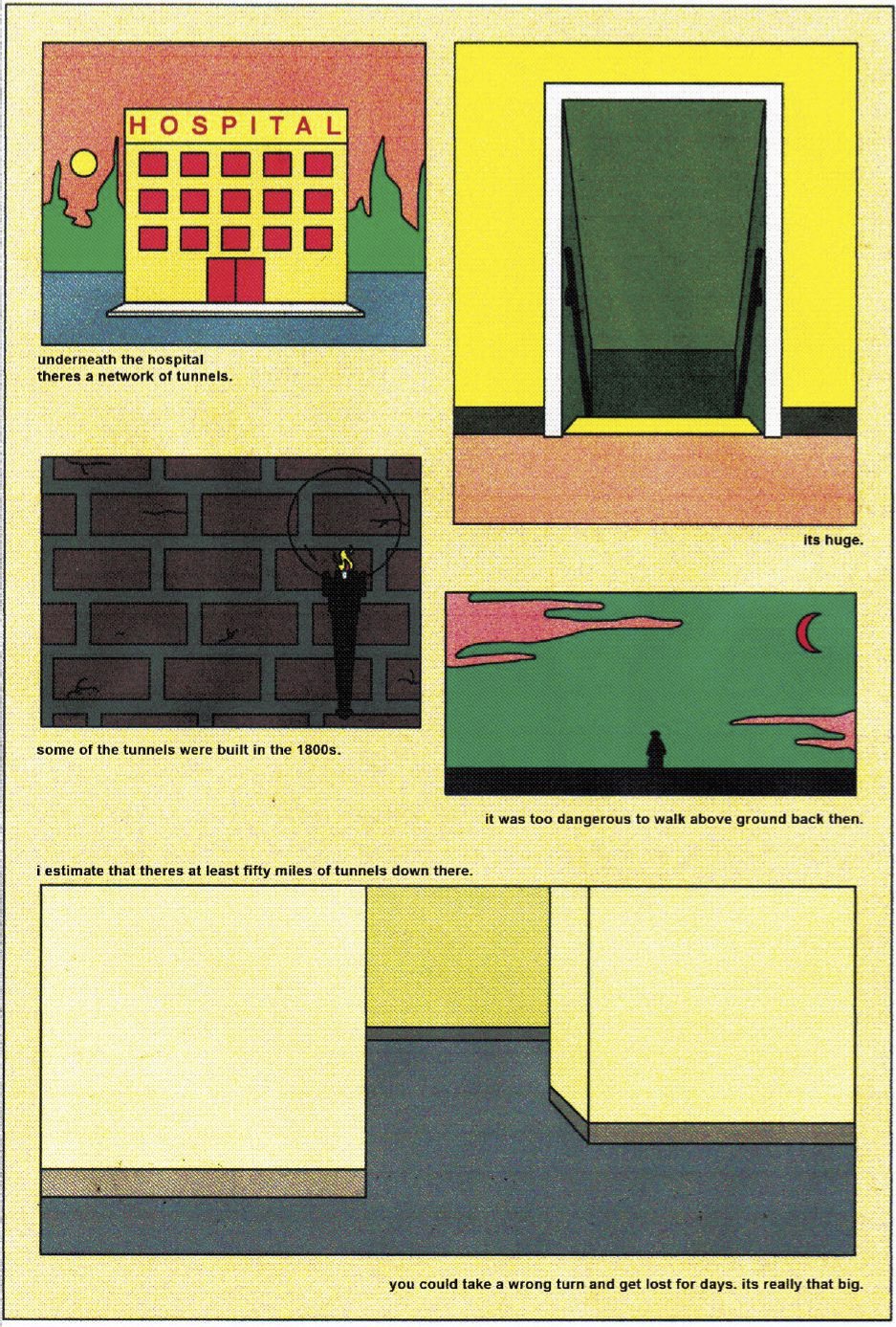

The story revolves around a computer tech who enters an apparently ordinary building, on assignment to repair a computer. He gets stuck in the building, and for the rest of the book the only thing he wants is to get out, though escape could be impossible for him, going through room after room, hallway after hallway.

Avery Hill Publishing released 2120 in English last May; the Italian edition from Coconino Press followed in September. Once I finished my translation, I asked George if we could chat about the book, and we met on Zoom. The book was so full of familiar feelings and fears, yet part of its language was quite new to me. I needed to know more about it.

-Valerio Stivè

* * *

VALERIO STIVÉ: When I wrote you about this interview, you told me you were going to be in the desert for a week or so. What was that about? I'm just curious, and maybe I should mind my own business. But it sounded strange. It must be because in Italy we don't have a desert, [although] it's probably just about time, considering climate change. Nobody ever tells you "I'm in the desert," unless it's a metaphor. Or you can think of Jesus and the 30 days he spent there. But I'm not a religious type and neither an outdoor type.

GEORGE WYLESOL: I saw a lot of Jesuses in the desert. [Laughs] Actually, I was on vacation with my wife. We went to Los Angeles and the desert is just a few hours' drive from there.

Yeah, I know. I was just surprised to hear that. It sounded funny to me, because judging by your book I wouldn't think of you as an outdoors type. It is such a claustrophobic story. The desert sounds like the total opposite of what you seem to be interested in with your art.

Yeah, that's a good point. [Laughs] I'm from the city, I'm definitely a city boy; I don't like the heat, I don't like bugs. I don't like to get out much, but that sounded like a cool trip to get away from Baltimore for a week.

So, how did you came up with the idea for 2120? At the beginning it looks like something that would come out of one’s mind while wandering around town looking at places and people and thinking, what's that guy doing? What's his job? What are people doing in that building, or what did people used to do in that abandoned place?

Yeah, kind of. I don't really know where the idea came from. It evolved over a long period of time. It wasn't just a spark. I used to work at this hospital that was empty; it was a building bought by a hospital, that they didn't really use. It was this empty office building that wasn't actually abandoned. I used to clean it every night. It was really creepy and lonely in there. Looking back at that time, it was really formative for me. I wanted to work with that setting. I started to think of what kind of narratives I wanted to tell in that setting, and I had been thinking a lot about surveillance and AI, shady government organizations, and that kind of thing. I wanted to work with those elements, and eventually it led to how it is now.

So, I guess your first book, Ghosts Etc. [Avery Hill, 2017], which shares similar settings, was like a demo for 2120.

Yeah, I didn't realize it back them, but it definitely worked as a demo for this book.

The scenery [in 2120] is a character as much as Wade, the computer tech guy. In order to have complete control of his movements, did you draw a map of the building where the story takes place, or did you enjoy getting lost with Wade?

Both. At first, I wasn't gonna draw a map because I wanted to get lost in there and find my out of the building as I was making the book. So I did the first draft without a map or any sketch. But then, when I went back to revise it, I realized I needed to add more halls and stuff. So then I sat down and drew a map, because it was so confusing to handle all the different files and remember which one led to which one. I had to draw a map and label each image, because there was like 200 JPEGs of the same hallway. It was so confusing, I had to label all that out.

Looks like you needed a map for the places and a map for the story, like a path to follow. It is not a linear straightforward story. Did you play [the game] yourself with the pages?

Yeah, I definitely needed a map for the first floor with the yellow walls. And the rest of it, I didn’t really need to map that out too much, but I really had to keep the story together, so I had so many drawings like sketches and notebook pages, like a paragraph of text with an arrow leading to another one, then another arrow bridging off. So, I had this big mess of guides with text and arrows everywhere, as I got to the end. It was really really messy. No one would have been able to understand it, but it was just a tool to help me figure it all out.

Would you call this book a gamebook?

Here we have Choose Your Own Adventure novels that are usually for kids, like middle grade, middle school age. I don’t really like the term, because it has that childish feel. I mean, it basically is, but this book is a little bit different, because you-- mostly you are trying to figure out your way around. I don’t really have a word for it. I just call it [an] "interactive novel."

Do you think you are making your readers choose for themselves or for the character?

That’s a good call. I would say it’s probably for themselves.

I thought a lot about that while I was translating the book.

I would say the readers are choosing for themselves and actually they don’t care about Wade - and then, when you get to the end, that idea is like the last choice you have to make.

I sensed that in some moments Wade seems to be speaking to the reader.

Yeah.

But it's not always like this - just a few times, like he is becoming conscious.

Exactly. Wade doesn’t really want to do certain things, because he is getting conscious that he’s being guided by the reader who wants to find out what happens and doesn’t really care how it all affects Wade. It is really subtle, like you shouldn’t be in over your head with that idea, but that’s definitely it. The idea of who’s in control. Is the reader really in control or is the writer in control of everything?

I felt like I needed to understand this while I was [translating] the book, because it’d probably require a different choice of words if Wade is speaking to the reader, or to an imaginary something that is plotting against him. Now that you tell me you were thinking about government and AI at first, I realize you are somehow criticizing those kinds of things, or maybe putting the reader in the position of thinking about those matters.

It’s like a book within a book within a book, right? First there’s [the first] half of the book, and you think, "what is this building?" And you get towards the end, and you realize you are facing something different. Then it’s really about you choosing and kind of acting in a way that puts your own interest first to see what happens in the end. You want to figure this out, you don’t care what happens to Wade. But then it also talks about how the author and the reader kind of interact. I’m the one who’s making all this happen, not the reader, not the people in charge of the building. There’s a lot of layers, it’s complicated.

Do you think that while working on the book you were experimenting and pushing the boundaries of the medium or just playing with it?

I was playing at first, I was kind of seeing how it would work if you have a book that you can play with like a game. And then, after I did a couple of drafts, as I felt my way through the story-- I didn’t plan it out, I knew it was going to be more serious and horror, rather than comedy. And then, when I had the third draft, I realized the book was going to be a little more philosophical.

I don’t know much about video games, but I understand that they had a big influence on 2120.

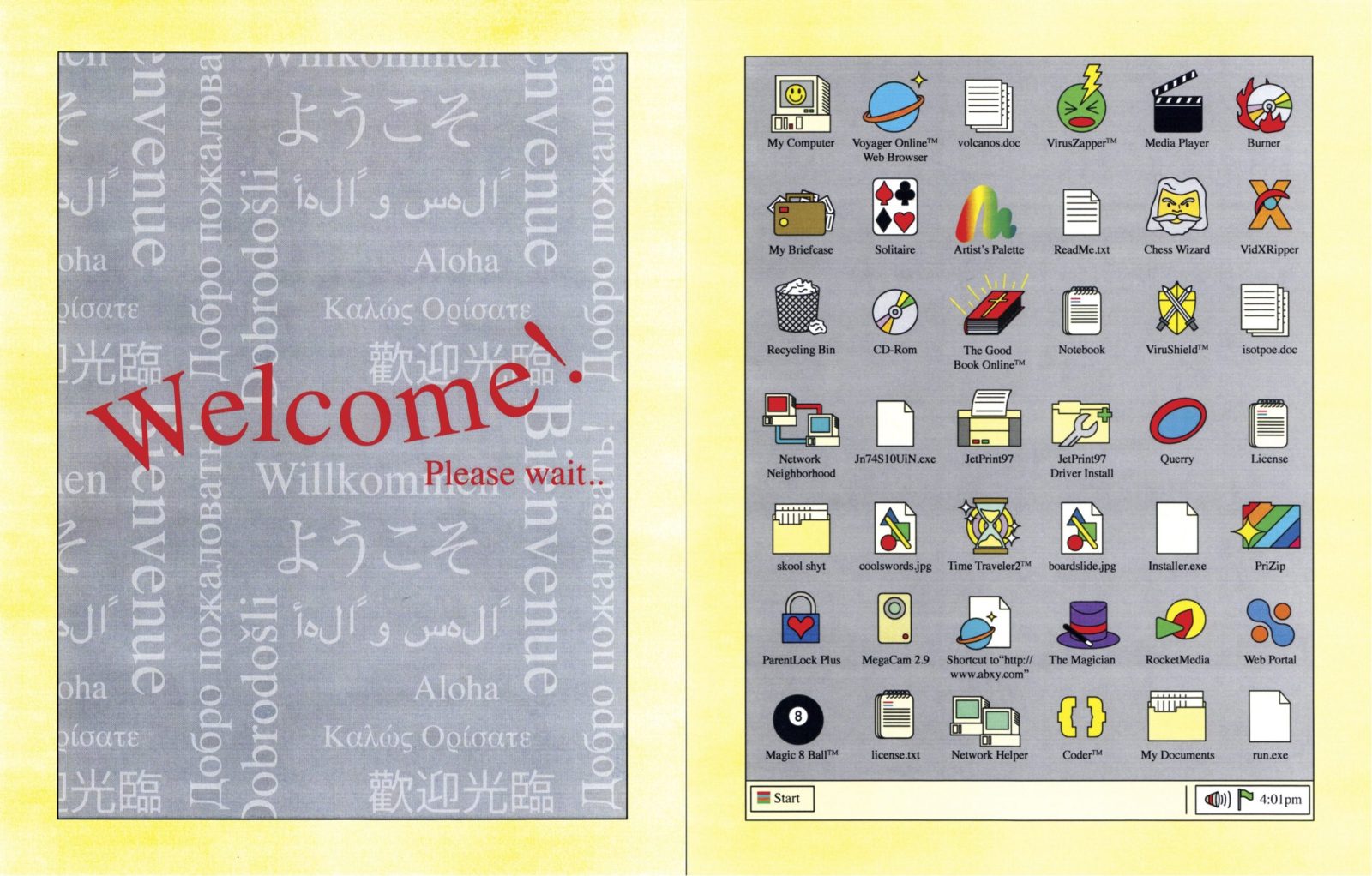

Yeah. I really like old games. I find a lot of the new ones too hard. But I did a lot of researching for my book Internet Crusader [Avery Hill, 2019], because that was a big part of it. I was playing a lot of old games from the '80s that you can find on the Internet Archive. I was really struck by how it is all a screen and some text, then you make a choice and you go to the next screen. This could be a book. So, when I finished that book I was just playing with the format. And I made a couple of zines, where you have to go this way or that way. And it worked, so I thought it had to be a great structure for the next graphic novel.

Had you considered making it a webcomic instead of a book?

I was thinking of making a game first. And it was too hard. I just don’t have the technical knowledge. I downloaded an easy game software, to experiment with, and even that was really hard. I didn’t have the time to teach myself. But when I make a book, I always make an eBook. In InDesign I can make a clickable bottom to go to a specific page of the book and it works so well. I didn’t know if a publisher would do that, but it is doable.

Since I don’t know much about video games, the kind of circular ending reminded me of the movie After Hours by Scorsese.

I never saw it. It didn’t come out of there. The most influential work on this was actually the game Silent Hill 2. You would never make the connection, but a lot of the tonal aspects of the puzzle actually came out of there.

Where you a nerdy computer kid when you were younger?

Not really, actually. I liked computers when I was young and I liked games when I was little, but once I turned into a teenager I liked to hang out and party and stuff. When I first went to art school, I thought I was really nerdy because I liked Zelda, which was like the most popular [series of video games] at the time. But then I realized I was not nerdy at all. I thought I was actually pretty cool compared to these people. [Laughs] People liked all these obscure comics from the '80s I didn’t know anything about, and now I like them, but at the time I didn’t know anything about that.

In your comics, there seems to be great fascination for the whole old internet aesthetic, Windows, etc.

I was born in 1989, so when I was young, like elementary school, I spent I lot of time at the computer. And I think it kind of stuck with me. That’s a formative time period to live through. So I think I was just taking that static inspiration from that time period.

When I was introduced to your work, one of the first things I was told about it is that you draw using a trackpad. How does that work?

I work in Illustrator. It is really easy to use a trackpad with Illustrator. For me it feels really natural. I don’t like working with a tablet; you need to have one hand on the tablet, one hand on the keyboard - it’s just awkward. With Illustrator, I like to have one hand on the trackpad, one hand on the keyboard.

To me, that makes sense with this kind of story, which has so much to do with computers. Do you think the technology influenced your art?

Definitely. I always think that the medium that any artist works with will have some influence on the imagery and the subject matter that they make. Most people don’t like using Illustrator, because it is so digital-looking, so precise and cold, but I really like that. It really lends itself so well to drawing perfectly straight lines, perfectly straight rectangles and squares. And that kind of precise geometry is like the whole structure of the building, with its linear perspective, rectangles.... If I would have drawn the same stuff differently, it wouldn’t have the same feeling, and I probably wouldn’t even have drawn that subject matter, because it would be too hard to get that precise on paper. But it’s actually really quick and fast to do it on Illustrator. So it totally dictates the type of imagery your working with, for sure.

How did you get there? Before reaching [this process], were you working with different styles and techniques?

I started drawing seriously in high school. I went to this free afterschool class at a really traditional academy in Philly. So I was actually really good with realistic oil painting and charcoal drawing. That was all I knew how to do when I went into undergrad: oil painting still lives. And then I went through the curriculum there, I just experimented a lot, I really wasn’t happy with doing oil painting, it was boring. So I started doing these really flat acrylic paintings of silhouettes. Which were really cool, but took forever to make. So one teacher told me, "why don’t you try experimenting with Illustrator?" I didn’t have any knowledge at all of how to make artwork digitally. He showed me in like five minutes how to use the pen tool, and that changed my life.

How and when did you start making comics?

Pretty late. I didn’t start until my second year of grad school, which was 2015/2016. I had already been studying art for a long time, and then I realized comics could be... cool. I never read them. I was never really interested in them. I made a lot of zines, throughout my time in undergrad and the first half of grad school. Then I did my first book, Ghosts, Etc., which is three shorts in one. I really liked that, and I thought it’d be cool to work in the longer form, which is where the next two came from.

I honestly wasn’t able to recognize any comics influences on your work.

Yeah. There weren’t any. I do not read many comics. I do read some. I care more about the art, so anyone who has a cool style, that’s what I look at.

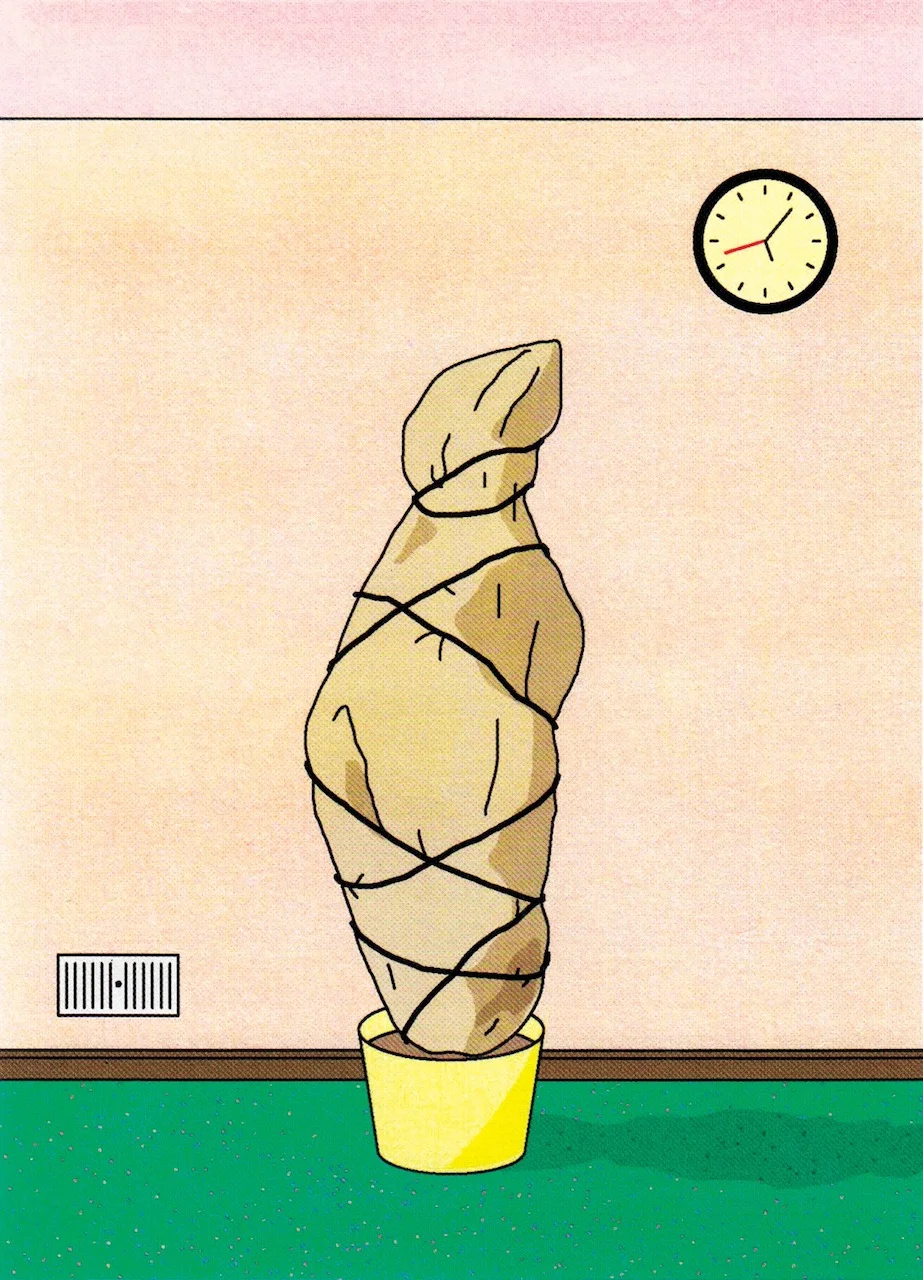

I have to admit that I wasn’t familiar with the concept of the 'liminal'. Was it a choice to explore this theme–some consider it a genre–or was it something you’ve always been attracted to?

It was very natural for me, because like I said, it came from working at a hospital for so long, with all its endless hallways and little offices that were empty. I didn’t think that there was a word for that either. I just liked that kind of environment. No one thinks about it, but to me it’s really interesting, visually. Because that space-- it’s so boring that anything that happens there becomes really significant. I remember when I worked at the hospital, there were these long empty hallways, and there would be like a little decoration, a little snowman just sitting there, and it was so creepy. It has a power.

That can open a whole a discussion into the concept of Hauntology as well, and into the music genre of Hauntology, for example.

That came up when I was doing research. I had already done a draft. I was just skimming the internet looking for stuff, reference photos for spaces, and I came across the album Everywhere, an empty bliss by The Caretaker, which was this-- they call it Hauntology. That was interesting, and I got stuck into a rabbit hole of that kind of artwork and that kind of space as well. I don’t know much about the theory of Hauntology, but I remember coming across that.

A sort of feeling of nostalgia for something that you probably haven’t even experienced.

Right. And that sort of ties into this a lot. There are experiences you never had, artifacts you don’t know about, but that you can relate to. I think that’s a good definition.

Also, reading your other stories, it seems you don’t like endings so much. And that makes me think of video games too. I mean, once a book is over, it’s over, but maybe a game is different - you have to go back there many times, do the same things again, before it’s actually over.

I like writing endings. There are technically two endings in 2120, but I wrote like 20 endings for this. I couldn’t figure out how to end it, so I wrote a bunch of endings, and then I came back to my very first ending that I came up with even before I started writing the book. And the other books... I think Internet Crusader is pretty simple, and the other ones are shorter comics. So, with 2120-- I don’t know. It ends, but there’s a lot of stuff you have to come back to, there’s a lot of stuff you have to find yourself.

You said you had many possible endings in your mind. Tell me one you didn’t use.

There were a lot of bad endings I used as a placeholder until I got there, and then I tried to make something better. It was going to end with Wade and the Fountain avatar having a conversation, and then Wade goes outside and looks into a security camera and then it zooms out and you are in a military base, and Wade is becoming conscious and the soldiers in the base have a fight on whether they should let him live or die. They let him live, and he hacks the computer and kind of shuts down their program, destroying himself and taking the military with him. That was okay, that was what I originally pitched to the publisher, but I knew it wasn’t that great. So it was better to have a general direction and figure out the rest later.

And maybe it was too hardcore science fiction.

Yeah, exactly. I wanted it to be more open-ended.

It was too cyberpunk and less philosophical.

That’s exactly right. It was too easy and predictable.

The post “It Evolved Over A Long Period Of Time”: George Wylesol on <em>2120</em> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment