(SPOT.ph) Who would have thought that a tragedy—the worst to befall a province in centuries—will revive an age-old tradition that’s responsible for producing exquisite works of art? The province of Bohol shows us how their recent history’s ugliest chapter gave birth to some of their most beautiful artistic treasures.

Death and Rebirth, Destruction and Restoration

The 7.2-magnitude earthquake that rocked Bohol in 2013 took the lives of 195 Boholanos and leveled most of the province’s prized heritage churches. The scale of destruction was massive, with seismologists saying the energy released by the quake was equivalent to 32 of the bombs dropped in Hiroshima. The tragedy claimed not only lives, but also took a toll on the locals’ spirit. Deeply religious, Boholanos were left heartbroken and hopeless upon seeing their beloved churches reduced to rubble.

There was so much work that needed to be done. The question was, “How do we start?”

Fr. Valentino Pinlac, Chairman of the Bohol Arts and Cultural Heritage Council, said the revival of the age-old tradition of wood carving for religious purposes, along with other creative industries, was conceptualized after the earthquake. The move to breathe new life into a tradition that was as good as dead in the years preceding the quake was initially an answer to the feverish call to restore the damaged churches. In the process, this renaissance didn’t only lead to restoration, it also lifted the locals’ morale while sharpening the skills of and giving livelihood to the wood carvers.

“The earthquake sort of awakened our innate skills and abilities. It was the earthquake which prompted us to show what we have (as a people),” Fr. Pinlac shared during an interview with SPOT.ph at Sta. Monica Church in the municipality of Alburquerque.

The practice of wood carving didn’t entirely die, but prior to the earthquake, carving was only for pragmatic purposes, like furniture production: “Anything that doesn’t translate to food on the table, or education for children, walang value ‘yon e [for the people]. No matter how beautiful the work or a piece of art, if it cannot be translated to something na kinakain, wala. In terms of religious woodworks, wala.”

The situation took on a rather surprising development in 2014: “After the earthquake, it started to develop again kasi one of the least damaged churches in Bohol during that time was Sta. Monica Church. The other heritage churches collapsed. I’m from Alburquerque, and I talked to the parish priest if we could do something. People have been crying because Bohol lost the heritage [churches]. [I thought] let’s do something here in Albur , because [Sta. Monica Church] is the only standing heritage structure [left].”

Fr. Pinlac and his colleagues took on the challenge and planned with the community and the pastoral and finance councils. “The resources were very limited especially after the earthquake. Then slowly, through the efforts of the community, I got the funding from the Bishop’s Conference of Italy. [At first], it was just wild imagination to restore Bohol.” They were able to build houses, provide livelihood, and conduct skills training.

Bohol Wood Carving

Wood carving in Bohol is done for the production of retablo (church altar) and urna (house shrine). These are not unique to Bohol, but the province takes pride in the high quality and artistry of their works. Aside from retablos and urnas, Boholano wood carvers also produce figures of religious icons. Fr. Pinlac clarified that having an urna at home, though not distinctly Boholano, is common in the province, “We don’t claim to have exclusivity of the practice, but it’s more popular in Bohol.”

However, this resurgence in popularity of artistic and religious wood carving is not without its challenges. Fr. Pinlac mentioned how they are losing valuable urnas because of antique collectors, “Before, they could get it for P100, P1,000, for a 200-, 100-year-old [urna]. When people don’t know the value of it, the historical and cultural value, this is just a piece of wood, wala e.”

He also lamented how furniture carving is on a decline, “We only have one famous wood carver for furniture and he is in Loboc. Pero, it’s like a vanishing trade, kasi most of the people prefer ‘foamy’ or soft furniture.” Still, he is very happy that wood carving for religious use continues to thrive, even amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Wood Carvers of Alburquerque

The small, sleepy town of Alburquerque is the center of wood carving in Bohol. At the back of Sta. Monica Church, one can find the carvers’ workshop—a hive of constant activity with the steady sounds of pounding and sawing, and the comforting smell of sawdust hanging in the air. During our visit, there were three carvers busy working on a commissioned urna, brows furrowed, hands moving deftly. So absorbed were they in their work, it’s possible they didn’t even notice our presence.

Albuquerque’s wood carvers are led by master carver Arsenio Lagura, who started carving when he was only 17 years old. “We only have one master carver. The rest were never carvers. They were carpenters, panday. He was the only carver. Then we had a partnership with the University of Bohol’s College of Architecture and Fine Arts. Combining our passion, we all worked together with the master carver trying to guide and teach them,” said Fr. Pinlac.

According to Lagura, it takes them about a month to make a regular-sized urna out of santol, but they also use ipil-ipil and molave. “‘Yun din ang ginagamit pang-ukit ng santo

The Magnum Opus: A Five-Panel Retablo at Sta. Monica Church

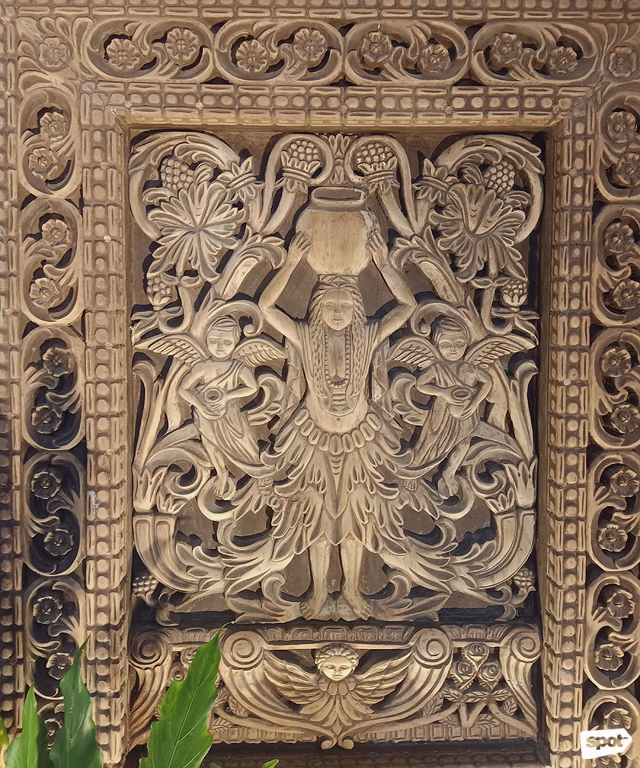

The biggest project to date for the Alburquerque wood carvers is the rebuilding of Sta. Monica Church’s altar, which consists of a three-panel main retablo, and two smaller retablos for both side altars.

It took Lagura and his team of 14 talented and dedicated carvers three years to complete the restoration. The fruit of their skills training and intense labor is nothing short of majestic and mesmerizing—truly a sight to behold.

The incredibly intricate retablo features not only religious icons, but is also a nod to Bohol’s rich heritage. Each ornate panel tells a Boholano story: there’s one with women carrying pots because pottery is a local industry; another features kalamay, a local delicacy. The main altars also have carvings of shells, which is a homage to the bountiful marine life of the island province.

More interestingly, the entire retablo made use of trees that were felled by the earthquake, “There were lots of trees which collapsed, especially [the] molave. We secured permits from the DENR (Department of Environment and Natural Resources) to make use of those [felled] molave for adaptive reuse.”

Adding to the charm of the 179-year-old Sta. Monica Church are the vibrant frescoes. Painted by local artists, the frescoes were part of a year-long restoration of the Church’s ceiling which collapsed during the earthquake. Thanks to the artistic treasures of Sta. Monica Church, it has become a tourist favorite, a popular stop in tours of the province.

Bohol’s Relentless Recovery through Art

Bohol is no stranger to tragedy. The 2013 earthquake has such a profound effect on the Boholanos that it remains a staple in conversations, with locals dividing their stories into either pre- or post-earthquake. Since last year, Bohol has been faced with another major predicament, and one with no end in sight just yet. A province heavily reliant on tourism, it’s needless to say that Bohol has been hit hard by the pandemic.

But Bohol is also no stranger to resilience and rebirth. The breathtaking retablo of Sta. Monica Church is proof not only of the Boholanos’ artistry, but also of their strength in the face of death, despair, and destruction, “When we are pushed to the limits, something beautiful comes out. I hope with this pandemic as well,” Fr. Pinlac mused.

“For as long as there are people who are willing to share their time and skills, heritage will never be dead. Just look at this,” he added while gesturing to the magnificent retablo with a huge smile on his face.

We couldn’t help but smile back in agreement.

[ArticleReco:{"articles":["85660","85609","85474","85292"], "widget":"More from spot"}]

Source: Spot PH

No comments:

Post a Comment