In September 2019, the human rights advocacy group PEN America published “Literature Locked Up: How Prison Book Restriction Policies Constitute the Nation’s Largest Book Ban” - an excoriating “briefer” encapsulating the group’s research into “book-restriction regulations within the United States carceral system.” The study, which examined prisoners’ access to reading material across a variety of prison settings, found that “[t]he reality of book banning in American prisons is systematic and comprehensive.” The study elucidated that books can be banned on virtually any grounds that prison administrators choose, and that appealing these bans is prohibitively expensive and time-consuming for prisoners and their advocates.

"Content-based" bans—those bans that constitute rejection or prohibition of reading materials on the basis of content such as violence or sexuality—are often arbitrary in their enforcement and opaque in their stated reasoning. These bans can originate from a number of administrative sources, but often stem from interpretations made by prison officials in the mailroom, exercising their own judgment in determining what reading materials are suitable for the prison population.

"Content-neutral" bans limit choice by limiting the channels through which books are procured. These bans argue that books can be used to smuggle contraband, such as drugs, within their pages. By limiting who can send books to a prison to, say, pre-approved booksellers with pre-approved offerings mailing from pre-approved distribution facilities, authorities argue that they can limit the flow of contraband into prisons. Although these claims are not backed by any great amount of evidence, little meaningful oversight coupled with a lack of urgency in formalizing regulatory guidance allows them to be upheld.

The PEN America study did offer some hope for prisoners and their advocates, however. David Fathi, Director of the American Civil Liberties Union National Prison Project, asserted in an interview for the report that the prison administrations that enforce these bans often capitulate when prisoners and their advocates put their ill-conceived policies (or lack thereof) on blast. “Prisons and jails get away with a lot of what they do just because people aren’t watching,” he said. “These are closed institutions, and they house politically powerless and unpopular people. So when you can get public attention, the prison system is often exposed as a paper tiger. Not every time, but often enough.”

The pandemic, however, gave prison administrators a convenient excuse to further isolate the already-isolated prison population, creating a new, worse status quo, even as healthcare guidance changes.

Comics, which I’d argue are still in their ascendancy in the United States as mainstream reading material and a legitimate artform, are equally subject to these rules. They are as misunderstood and maligned as any other medium - especially genre fiction, in that violence and sexual content are seen as disqualifying factors, rather than narrative tools. Yet organization across the country work toward getting comics into the hands of prisoners, arguing that comics are uniquely valuable to the incarcerated population in the way they offer a visual element for people who may not read widely.

The organizations interviewed below vary in size and scope. They serve their respective constituencies along various demographic and geographic lines for reasons that range from the humanitarian to expressly political. Regardless, they share the mission of getting books into the hands of prisoners. To take up such a task in a steadfast, unwavering way on such constantly shifting terrain is as maddening as it is rewarding. Those uninitiated in such Sisyphean work might call it selfless. On the contrary, I would argue that it is an act in service of a shared humanity. For this interview, I spoke with Kelly Brotzman, the managing director of the Massachusetts-based Prison Book Program; Jodi Lincoln of the Pennsylvania-based Pittsburgh Prison Book Project; the North Carolina-based Asheville Prison Books; and the Wisconsin-based LGBT Books to Prisoners.

-Ian Thomas

* * *

Ian Thomas: Can you talk about the origins of your respective groups? When were they founded and by who?

Asheville Prison Books: Asheville Prison Books was founded in 1999 by folks in Asheville (western NC); it’s always been very grassroots, but has also undergone many changes over the years - sometimes it’s been comprised of a handful of rad/anarchist-identified folks who see the project as “political,” and at other times the folks involved represent a broader/less subcultural volunteer base.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: LGBT Books to Prisoners was founded out of Wisconsin Books to Prisoners when longtime volunteer Dennis Bergren saw the quantity of requests for LGBTQ materials. He originally asked if [he] could just help stock gay books, but eventually ran the project single-handedly from his home.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: Pittsburgh Prison Book Project was born in 2000 as Book ‘Em when founders, Etta Cetera and Athena Kazuhiro, learned from an incarcerated friend of the nearly non-existent educational opportunities that U.S. prisons afford their prisoners. Not only was the library at her friend’s prison under-stocked, but it was impossible for inmates to request new materials or to receive books from friends and family. Partnering with The Big Idea Bookstore and the Thomas Merton Center, the book project was formed and has been filling an important need for over two decades.

Prison Book Program: Prison Book Program was born in 1972, [so] we’re in our 51st year. And it was the project of members of something called the Red Bookstore, which was a bookstore in Cambridge, Massachusetts that only carried leftist genres. So, you know, Maoism, Black Liberation, that sort of thing. And in those days they saw people in prison as one of the many groups—not the only group, but one of the many groups—suffering from systematic oppression. So, it really grew out of the counterculture years in the late '60s and early '70s. It was founded by activists - most of the original people were Prisoners’ Rights activists. That that's how they would describe themselves.

Do you serve any specific geographic area or demographic?

Asheville Prison Books: We send books to folks locked up in North Carolina and South Carolina, in any type of carceral entity (local jails, immigrant detention, state prison, federal, juvenile, locked mental health ward, basically anyone who sends us a letter from NC or SC we’ll try to send them something). In the past, the project also served GA and TN, but we stopped serving these states approximately five years ago.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: We serve LGBTQ people incarcerated across the country.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: We serve people incarcerated in Pennsylvania.

Prison Book Program: We do not. We serve all 50 states, Guam, Puerto Rico - if we get a request from the Virgin Islands, we fill that too. So, we have the largest service area, we believe, of any of the books to people in prison movement. There [are] maybe several dozen groups in that movement nationally.

Can you speak to what that means in terms of fulfillments and packages mailed?

Prison Book Program: Last year was an all-time high for us. We’ve only added staff in the last in the last 18 months, so it was an all-volunteer collective for 49 of its 50 years. Things happened funding-wise that made it sensible to bring on two people, myself and one other person. Because of that, we’ve been able to hold far more volunteer sessions. The pre-COVID high water mark was about 12,000 packages - and a package typically contains three to four books and an assortment of print resources, some of which we copyright and publish, some [of which] we borrow from other sources. But last year we hit 15,231, so we fulfilled that many orders with-- again, the standard package is about three pounds' worth of books. So, if you count it as 3.5 books per package, it’s over 50,000 books.

Is your group staffed by volunteers? Have most of the people who do the work been directly affected by incarceration?

Asheville Prison Books: Yes to the first question, no to the second. Formerly incarcerated people and their family members are involved, but it’s not a majority.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: Our work is entirely staffed by volunteers. Some have been system-impacted. Most are LGBTQ or advocates and allies. Many are abolitionists.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: Yes, [we are an] all-volunteer organization. Leadership group of 10 people and a huge network of volunteers who come to packing sessions. Not most, but I think many people develop friendships with people on the inside as a result of this work (I know I have). We do get system-impacted people volunteering though.

Prison Book Program: We had over 1,000 volunteers last year. Originally, it was five to eight people gathered in the basement of the Red Bookstore, once a week, fielding 50 requests a week, and they were pretty much exclusively devoted to radical books and progressive books. Now we carry everything. Our volunteers come to us for a wide variety of reasons. Some have loved ones who are dealing with incarceration. But I would say there's a fair amount of overlap between our volunteer base and the prison activism groups, locally. Some people come because they’re religious, [as] part of their practice. A lot of students come to us because they need service hours. But I would say more than half of our volunteer base were identified as someone who's concerned about the Criminal Justice complex from policing to prison.

How does your group acquire materials for distribution to people who are incarcerated?

Asheville Prison Books: [The] vast majority of books are donated directly by individuals getting rid of their books. [A] smaller number are donated by businesses or institutions (libraries, bookstores) liquidating parts of their inventory or collections. Specific requests are sometimes filled on a one-off basis using store credit we’ve built up over time at local used book stores. Every now and then we’ll post on social media to source specific titles, or to ask folks to buy picks off of a “wish list” we have at a local bookstore. Infrequently, we bulk purchase a very high-demand title - really, only for dictionaries.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: We acquire materials mostly through donations. We have relationships with publishers and authors. We also work with LGBTQ book prizes to get copies of books nominated for awards after the judges have read them. We'll buy high-need books.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: Primarily donations from the public - individuals and book drives run by groups. [We] purchase books as able to supplement donations.

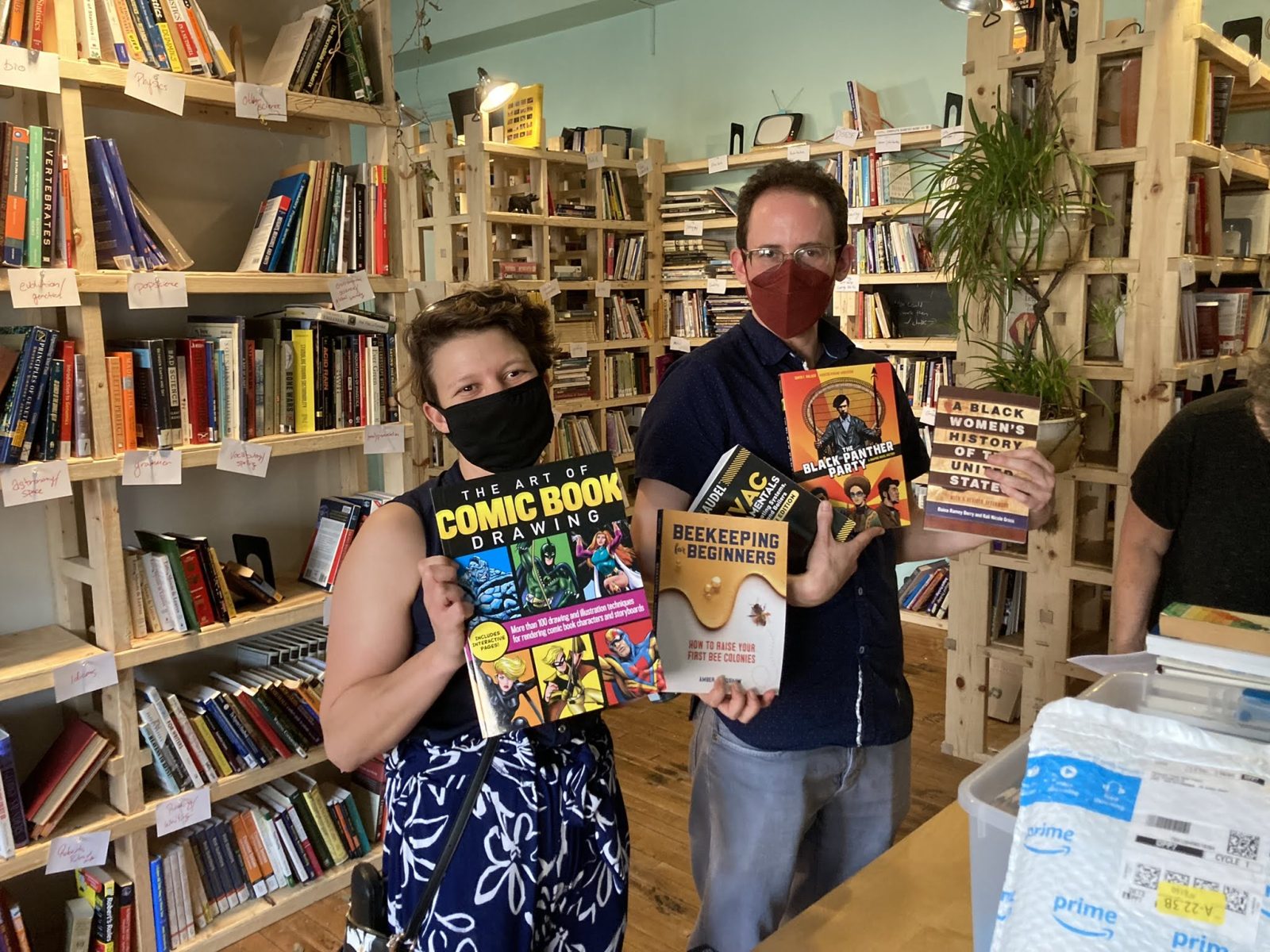

Prison Book Program: I always say it’s a thousand tiny streams forming a mighty river. Most of the books just walk in off the street. People bring us their personal books. We hold four volunteer sessions a week, presently. We may do more in the future, [but] they can bring books any time we’re there and holding a volunteer session. So, it’s basically just community donations. We do have relationships with some public libraries and their “friends of” fundraising arm. The main way that the “friends of" fundraising arms raises extra money, beyond taxation, for their libraries is through a book sale. Maybe once a year or several times a year, they invite us to come at the end and scoop up anything that we need, so we have good, strong relationships throughout the region with those kinds of things. We have a team of what we call 'book fairies' who are highly trained in what we need and what is constantly under-supplied on our shelves. They scour all the local thrift stores, second-hand shops, [and] that sort of thing, for books at less than two dollars a book, and we reimburse them for those purchases. And then there are the books that we directly purchase at wholesale, and those are things like dictionaries. That is our most common request. We sent out about 5,000 dictionaries last year. Only recently, since we've had the means to do so, we purchased those by the thousands at a very, very bargain-basement price. It’s a college-level dictionary. We get a lot of good feedback on it from our readers and recipients. We're starting to branch out a little bit. A huge thing in prison is learning how to draw or picking up an art skill, so we just never have enough ‘learn how to draw’ books on the shelves. We found some creative sources for those. I would call it targeted acquisition. Our purchase budget for the current fiscal year is about $25,000.

How do people who are incarcerated contact you with requests?

Asheville Prison Books: They write to us at our mailing address. They find out about us through word of mouth, or the various resource directories that exist for incarcerated people.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: Incarcerated people contact us by mail, occasionally by email. We sometimes receive requests via a friend or family member.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: They write us letters.

Prison Book Program: 99% of in the form of a handwritten letter. So they just take a pen and paper, tell us what they like to read. The people who've been writing to us for years—and many people have—they know the drill. They know to request a category of book, maybe an author. They know not to request a specific title, because what we have in stock is just constantly changing and we can't guarantee specific titles. Sometimes new people will request specific titles. We try to get as close as we can. Or, if it’s a legitimate study interest, we really think they deserve to have that. We have a special request process where we post it to one of our wish lists and wait for a donor to buy it, and then we give them exactly what they're looking for. That process takes a little bit longer. We now have an online form where a loved one on the outside who has access to the internet can fill out a book request on behalf of their loved one, and that has massively increased in the last year because didn't really have that methodology before. We did recently do some work with a system called JPay dot com, which is not email, but it's like a secure messaging platform. We reached out to some people who have have specifically onerous processes at their prison. They have to have specific titles approved by the mailroom within 30 days of receiving the books, which is just so out of sync with our fulfillment process. So, we've been trying to utilize that messaging system a little bit more with people in those prisons who were making requests, but that's that's a very small percentage.

What do people typically request?

Asheville Prison Books: The most frequently requested items are books about starting a business, learning a trade, dictionaries, and mass-market thrillers. After that - general fiction, classics, foreign language dictionaries, westerns, and romance.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: What don't they request? No, seriously, we get requests for EVERYTHING... literally we get asks for anything you can think of.

Prison Book Program: We find that the reading interests of the incarcerated population very much mirrors that of the non-incarcerated population, with a couple significant exceptions. Like I said, the most common request is dictionaries, and the reason, I believe, is that it is a key to all the other books that we can provide them. And it's also the key to understanding a lot of their legal paperwork, which has a lot of fancy, jargon-y words in it. So, it unlocks the world of books for them. Then, we have a lot more requests for nonfiction than for fiction, and I think that's because a lot of people are looking to learn a skill. Taking up a language study is very popular in prison, taking up an artistic skill, music skill, whatever, very popular. We get a lot of requests for hobby books [like] crochet, origami. Trade skill books - maybe it's a career they hope to go into when they're released, and the building trades are one of the few decent jobs that you can generally still have with a felony record. We get a lot of requests for things like exercise, gardening, fitness, [and] food nutrition because the healthcare is so bad and the food is so bad that people are looking to basically keep themselves well and healthy. Most of the requests contain some wishes in both fiction and nonfiction and, obviously, on the fiction side, the most popular stuff is your genre fiction - sci-fi and fantasy, and, especially with some of the women's prisons, romance. We have tons and tons of thrillers. People love their Lee Child, they love their James Patterson. And then comics - comics are a huge area for us. They are very popular. We think there's a couple of reasons for that. It's exciting to follow a story, and they're also good for people who are just gaining fluency in their reading.

Are there controversial genres or titles that you refuse to supply in fulfillments?

Asheville Prison Books: This is a great question, and the answer is unclear because we don’t have a policy or set of agreements around this. In practice it is usually not relevant, because we don’t send specific requests; we’re just picking from what we have available in the office. So it probably comes more into play when we receive donations and shelf books [at the office], since that is mostly when people are deciding what to keep and what to re-donate. This is a subjective process and happens on an ad hoc basis, so if people remove content they find objectionable from the shelves, other volunteers likely wouldn’t know about it. Of course, as people fulfill requests, they also use judgment around what is valuable, and may avoid sending a book they find objectionable, but again, it would be an autonomous decision that doesn’t fall under a policy.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: We don't stock white supremacy/hate group literature, although we do get requests for it. Those individuals generally still get sent books - either general fiction or other subjects if they requested them. We do stock Holocaust/WWII books.

Prison Book Program: Yes, we don’t carry True Crime. It would never get into any prison. So, stories about mobsters, books about serial killers, we don't carry that sort of thing. We get requests for Erotica and, generally speaking, they probably wouldn't get in either. We don't like to censor, but it's a struggle. It's just one of those things that's constantly being debated. Martial Arts is another interesting area because a lot of people are needing to defend themselves, but again, anything that is instructions on anything that could hurt someone is probably going to get screened out by the prison itself anyway. We know that a lot of Martial Arts are really about wellness, so we're just constantly negotiating this. Some manga and comics that are hyper violent—like they have headshots and extreme nudity—there's a rating system I think on some of those things, so, the sort of super X stuff, we try to stay away from.

Since we are here to talk about comics, can you tell me about people requesting comics? Does it happen frequently?

Asheville Prison Books: People consistently request comics and related media (graphic novels and manga). While it’s not the “top” ask, we send it out frequently.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: We receive some requests for comics. In general they're harder to send because of restrictions about images (particularly nudity). Like all requests we receive, comic requests run the gamut from Marvel to Queer graphic novels to anything in between.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: Yes we get a TON of request for comic books. Based on an analysis of our letters in 2020, 10% of letters included people asking for comics. We also had 5% of letters asking for graphic novels and an additional 5% of people asking for manga. We're currently sending over 400 books a month, so we're sending a ton of these titles!

What kind of comics, in your experience, do people ask for? Are you receiving requests for specific titles?

Asheville Prison Books: We don’t often receive requests for specific titles, but that’s probably because people know that our project doesn’t provide specific titles (not just for comics, but in general). We do get a lot of requests for manga, and sometimes for specific superheroes (Batman, Superman, etc.). One notable thing is that often we’ll get requests for comics and manga along with requests for drawing books; some have told us they are requesting comics as references for drawing.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: We fill requests with books that match an individual's request as closely as possible. Sometimes that isn't possible because of restrictions at a particular facility.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: Our requests are either for "comics" in general, specified DC or Marvel, or a specific comic book superhero (Spiderman, Batman, Superman, Hulk are ones we get specifically called out. All mainstream.)

Prison Book Program: DC and Marvel are definitely the most popular - the major universes and superhero type things. Those are always popular. We don't get a ton of requests for things like Archie, those sorts of things. We have what we think are some comic book aficionados that correspond with us regularly. They'll ask for specific issues and we always sort of debate ‘Should we put it on special request list?’ if they're trying to complete a series or something like that. Because we operate so heavily on community donations, it’s just so hard, and putting comics on a wish list on Amazon is actually kind of hard to do. We will take any kind of comic that people bring us, but on the request side I would say the floppies are very, very popular. In the last couple of years, Black Panther has been huge. Green Lantern. Some people request specifically manga, but there's a fine line in manga, as well. You talk about things we don't carry, some manga, the way they’re drawn, make the characters look like small children. And if they’re drawn in a sexualized way, we’ve had problems with them getting rejected by the prisons. If there’s a character that's female and drawn to look like a young girl and dressed provocatively, we have a lot of trouble with that. We take them and put them on the shelves, but they get rejected a lot. But the manga [is] very popular - not only the manga themselves, but also things about how to draw manga are very popular.

[Specifically to Prison Book Program:] I was wondering if you could repeat, in anecdote, about how you suspected that within a certain facility, the folks were trying to put together a whole run of comics?

Prison Book Program: [We] sometimes have multiple requests come in the same envelope, because a stamp is 63 cents and it's expensive if you're making 14 cents an hour, so you can put as many as will weigh an ounce in there. So, we got a single envelope containing small slips of paper, tiny little slips of paper from many different residents - and that's not uncommon, that happens a lot. I can’t recall the story right now, but they were all for different issues in a particular narrative arc. We suspected that they were writing to multiple groups as well, and trying to fill in the gaps, trying to put together the entire story. We did we put some of them on the special request list. We got some of them, [but] we didn't hit 100%.

Do you have a big supply of comics from which to draw?

Asheville Prison Books: It ebbs and flows depending on what has been donated. It’s usually feast or famine in that regard, as we’ll have few or no comics for a while, and then someone who is a big comics fan donates a huge number of titles and we’ll be set for a while until we run out again.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: Our library is constantly in flux, depending on the donations we receive and the requests we're filling. Sometimes we have lots of comics, sometimes many fewer.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: We received a large donation of comic books a couple of years ago (about four of the long white boxes), and those have kept us well stocked on top of additional small scale donations that come through. When we run out of that supply (probably sometime in 2023), we'll do a large push for comic books. We're also working on creating a partnership with comic book stores in the area.

Prison Book Program: At the moment, we are okay with comics. It has historically been one of our high-demand, undersupplied categories. One of our book fairies now is a comic book expert, so we’re very fortunate to have her services. She will often take books that we can’t use—and there are a heck of a lot of books we can’t use—and take them to her favorite used book places and turn them in for store credit. She uses the store credit to get comics. She's one of the ones who we've authorized to spend a little bit of money here and there. Again, when we get a manga that's hyper-violent or whatever, she’ll take it into the comic book store and turn it into something a little bit cleaner that we can use.

What kind of efforts do you make to procure a title, should you not have it?

Asheville Prison Books: If the book is important for completion of an educational goal, we may go to an extra effort to procure something. Or sometimes a request will speak to a particular volunteer, who will choose to fulfill the request (purchase something) on their own to fulfill the request or put the word out on social media to see if someone will purchase the book.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: We generally ask people not to request specific titles because it's much harder to fulfill title requests compared to genres. If someone needs something in a series, we'll do our best to find it. We keep a list of every book we send to help us keep track of this, especially if someone just asks for more of what they've previously received.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: None. While we do this for other genre requests (specifically tied to education, personal betterment, business, etc.) we do not attempt to procure specific titles. If someone asks for a title we don't have, we will still send them other comic books.

Prison Book Program: We have a special request queue. It takes the person a little bit longer to get their books, but, even if it's just, like, a book in a fantasy series that they're missing, we will put that on the special request list on our Amazon Wish List and wait for someone to buy it. When [somebody buys] their book, it takes another 30 days or so for them to get their book, but they always get bought. It's so crazy. But people love to buy when it is going to a certain person. Sometimes, they’ll even leave a note. It doesn’t work well for comics, though. I don’t know why, Amazon is just really weird that way. We’ve talked about the possibility of keeping a wish list if there was online functionality with one of our large comic book chains here, New England Comics. I don’t know if they have that.

What kind of challenges arise in fulfilling requests?

Asheville Prison Books: The limited selection of books relative to the breadth of requests is the biggest barrier. The other barrier is the rules from the facilities, because we may have, for example, a hardcover book that fulfills a request, but we can’t send it due to facility restrictions. There are also two NC state prisons where our project is currently not allowed to send anything. We are currently working to reverse those bans, but it takes time.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: Prison restrictions vary state by state and prison by prison. There can be both content restrictions (such as nudity, which can extend to medical books on topics like transitioning) and format (such as no hardcover, new books only, restrictions on the number of books, etc.). Some states require that books come from an approved vendor or specific publisher; we generally can't send to people there. We keep a spreadsheet and try to keep it updated if we receive a rejection (either by formal letter from the state or an individual telling us that books were not received), following news stories, researching state guidelines, and asking those making requests to let us know of any restrictions at their facility. We've tried to fight some restrictions. Overall the system is arbitrary and often hides under vague statements like "threatens the safety and security.”

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: [We do] not usually have specific requests in stock. Most comics we get donated to us are not the most mainstream popular characters. Sending a few books that are in not order in the same series - ideally [they] would send someone three to five comic books that are in order.

Prison Book Program: Postage is always a thing, and it only ever goes up. Media mail has gone up in the past year with inflation and everything. Our average three pound package is now $5.05. It’s a major resource constraint. After salary, [postage] is our single biggest item. Our postage bill last year was $65,000. It adds up. The other issue is just the prison rules. Each prison has one warden and, even when they say there's a statewide policy, that is not true. It is the warden who decides whether to implement it, how to implement it, and, even then, it filters down to each mailroom. Each mailroom sergeant or property sergeant interprets the rules differently. We try really, really hard to keep up. We have a massive, massive spreadsheet with a tab for each state where we keep track of the rules. Whenever we get returns, we call the places, [asking] ‘What did we do wrong?’ It's just a constant struggle to stay on top of what the rules are at each place. Sometimes there's a maximum number of books. Sometimes they have to be in 'new' condition. Sometimes they don't accept used books. More and more places are requiring books to be in new condition. 90% of our books are used, so that's a problem for us. The primary sources for [new books], of course, are the wish list. We have more new books on our shelves than we ever have had before, but it's not enough.

What is driving that policy?

Prison Book Program: It’s because they think used books can contain contraband or a message of some kind. Someone could hide drugs in there. Drugs are getting into prisons. Some people say it’s easier to get them in there than on the street, but they're not coming in books. Maybe in a small isolated case. They’re coming in with people, [but] they always use that as an excuse to put the kibosh on books.

Do you observe reading trends within or among facilities?

Asheville Prison Books: Not much, but we don’t track what we send, so if we had data to look at we might see some kind of trend emerge, which would be interesting. One anecdotal observation is that requests from women’s prisons request content around knitting/crochet and games/puzzles more frequently. We also notice that requests from women’s prisons often come “bundled” (multiple people putting a slip of paper requesting titles in the same envelope). It’s interesting having a window onto that sharing/coordination happening.

Prison Book Program: We do observe trends. There are things that have a moment in prison. One that’s having a moment right now is crochet. Everyone wants to learn how to crochet. I don’t know if they just made yarn available or what. Another one that had a moment was Wicca. Everyone wanted to become a witch. That’s still having its moment, but it’s on the waning side. The one thing they have guaranteed to them constitutionally is the right to practice whatever religion they choose. So, they experiment. Druidry, witchcraft, non-conventional, non-mainstream religions are a trend, for sure. We get a lot of requests for Asatru and Odinism, which is a little bit [related] to the white supremacist stuff, but those are definitely having a moment. There's a lot of people who convert to Islam and want to learn their practice. Yoga is having a moment. There are a lot of prison Yoga programs, so we're getting a lot of requests for Yoga books. On the comic side, it kind of goes with the movie releases, what’s popular.

What are the rules that need to be observed when mailing materials to incarcerated people? Do they vary from prison to prison? How do you keep track of them?

Asheville Prison Books: Restrictions vary per facility and seem to be arbitrary and random, but can also change based on the whim of mailroom staff or the warden. We used to keep a binder with a list of all the facilities we mailed to where we would write down restrictions when we were informed of them, but we stopped doing this a few years ago because the process of looking up restrictions every time we fulfilled a request was so time-consuming and did not serve much of a purpose.

Some examples of the types of restrictions we see: nudity/sexual content (which often includes anything LGBTQ-related, even if it isn’t explicit - this is a form of discrimination that has gotten some LGBTQ-based book groups banned from sending to facilities, so we try to work with those groups to cover those gaps because we aren’t targeted in the same way); ideas deemed to be a “security threat,” which includes black liberation-related literature; restrictions based on size, such as no books thicker than two inches; restrictions on the number of books people can receive (Pender CI [Burgaw, North Carolina] recently implemented a one book per week restriction); and lately some facilities have moved to only accepting books from Amazon (Alexander CI [Taylorsville, North Carolina], for example).

One big thing that varies from prison to prison is whether or not they will accept hardcover books. As a general rule, we just don’t send hardcover books or accept donations of hardcovers because a lot of facilities won’t take them.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: PA Department of Corrections rules are standard across the board, so that makes our system easy. Generally, content restrictions-- in terms of comic books, that mainly applies to nudity, but we haven't had anything rejected or self-censored. One federal prison in PA does not allow hardbacks. Jails are [not] transparent and not open about rules.

If something is rejected, do you receive feedback as to the reason?

Asheville Prison Books: It depends; if a book is rejected due to the content, the prison is supposed to send it back along with a form explaining the reason for the rejection. In practice, this doesn’t always happen, and sometimes our packages are simply thrown away. When we’ve faced “blanket bans” (of our project sending any books, regardless of the content), we usually find that out from the package being returned and stamped with a message like “Contents not approved” or “Not an approved vendor” or simply “Refused,” and then we have to call and follow up to figure out why.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: From PA state prisons and Federal prisons - yes. County jails - no.

Prison Book Program: When you send as much mail as we do, you're going to get returns. Most of the returned books, they’ll return just the offending books, and they have a form where they have a long checklist of checkboxes, and they'll check which reason they think it's violating their policies. We get drawing books returned from the state of Florida all the time because they can be used for tattooing or tattoo patterns. It's very hard to get any drawing books into the state of Florida and they're constantly and checking off that box. Now, the easiest thing for them to do is throw them away. We have no idea how often that happens. Our return rate, generally speaking—and we do track it very carefully—is 3% or lower.

What kind of responses do you generally receive from the community in response to the work you do? What do you wish people better understood about the experience of people who are incarcerated?

Asheville Prison Books: We get very positive feedback from our community; almost everyone is supportive of folks inside having access to reading material. There seems to be a generalized understanding that mass incarceration doesn’t serve the public good for the most part, and that people inside have a legitimate need for access to print material, for education or just to pass the time.

In terms of things we wish people knew, one of the biggest misconceptions is that people inside have access to books (a prison library) that is stocked and accessible; they are surprised to hear how cut off and starved for information people are. Another misconception is how prevalent private prisons are (they actually account for a tiny percent of the incarcerated population), and a related misconception is that bad or abusive prison conditions stem from a prison being private (that is, people are surprised to learn that human rights violations are just as common in public facilities).

Another thing people frequently misunderstand is just how much prison officials lie. [For example,] using “contraband” as a justification for banning our project from sending books, or implementing unpopular policies like third-party mail digitization. People on the outside often take prison officials’ security-based narratives at face value, and it would be helpful if they were more skeptical and critical of the narratives authorities present.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: People are generally supportive of our work. We receive book donations from all over the world and have monthly sustainers the help us pay for posting the books. People generally don't understand how arbitrary and punitive restrictions can be, how dangerous and isolating prison can be for LGBTQ folks, or alternatives to prisons.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: [The] community is extremely supportive, and we get a ton of support both with volunteers and book donations, but also financially. I think engaging with our organization is a great way for the public to get a close and intimate connection with people behind bars, and it can be extremely humanizing - something that the system is designed to prevent.

How did COVID affect your operation, and is it still factor?

Asheville Prison Books: The bookstore where our office is located has had reduced hours dating back to 2020, which has made it difficult for some volunteers to come into the office. We pivoted to having our “packaging parties” (where we prepare packages for mailing) outdoors, which was more work but pretty positive in terms of outreach. But the biggest place COVID had an impact is inside the prisons: more people locked down for longer stretches of time with almost no access to other programming, education classes canceled, no opportunities to go to whatever small library the prison may have had. We receive a noticeably higher volume of requests now than we did before the pandemic; we can’t say for certain why this is, but it feels related to the above factors. In other words, the books to prisoners network (our program and programs like it) became even more of a lifeline to critical resources when the pandemic narrowed the options folks had inside.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: We shut down during COVID, but mailed everyone on our list an activity booklet. It took us a bit to rebuild our volunteer base after COVID.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: [We] did not have public packing sessions for approximately a year. The number of packages sent was greatly reduced. No longer a factor.

Prison Book Program: We're back to full capacity and the church that rents space to us has dropped all COVID restrictions, but early on we just closed. There were no volunteer sessions. There was nothing for probably six, seven, eight months. We did start having volunteers back, like four at a time. Our space is really weird. It's like this long, long, long space. We would have four, five, six, seven people for social distancing. This was even prior to vaccines. In 2020, we still managed to get out like 5,000 packages of books. In 2021, I think we managed to get out about 7,500 packages of books, which is amazing. And then in September 2021, we resumed capped volunteer sessions, capped at 30, and now we're back to our standard, which is 40 [volunteers] per session. It got us very much behind. We had a nine-month backlog. And that's true for all of the groups in the movement, but we eliminated our backlog in 2022. So we're back to our 60- to 90-day response time.

What kind of feedback do you get from your constituency?

Asheville Prison Books: People are very thankful to be thought of and given free books, so we receive a lot of thoughtful thank you cards and letters. We've also received a few in-person visits from former prisoners to thank us, and often have books returned once a prisoner is released. There have been times we’ve also received critical or constructive feedback about how we could be doing better, and we try to take that to heart wherever practicable.

LGBT Books to Prisoners: We get lots of letters thanking us for the books and the connection (all of our books come with a personal note, except when prisons don't allow this). We've sent over 12,000 different people books over the last 10 years.

Pittsburgh Prison Book Project: The letters people write to us are filled with so much gratitude for receiving books in the past and are very excited about their next shipment. [A] survey we ran in 2019 showed that some people weren't getting the type of books they requested and weren't satisfied with their package, which has made us focus more on stocking high-in-demand but low-donated books by purchasing them or creating partnerships with book stores, etc.

Prison Book Program: Unending gratitude. You should see some of the things that people send us. They send us their artwork. They send us poetry. They send us notebooks. They send us popsicle stick boxes. They send us soap carvings. It’s so isolated in there and so many people have grown alienated from even their closest friends and relatives, that just being acknowledged as a person who matters, a person whose reading interests matter, it’s medicinal. It’s profoundly healing and moving to a lot of our recipients. People tell us they’ll just cry when they get one of our packages. We just get tons and tons and tons of thank you notes. They can’t believe it sometimes. People have said that it saved their life [when] they were suicidal. They didn’t think anyone cared about them they didn’t think they would ever have contact with anyone in the world again, and then they got a package of books. Especially during the pandemic, I don't think it’s a stretch and it's not hyperbolic to say that programs like ours did save lives. There was nothing to do, literally nothing to do. Every single program shut down. There was no chow hall. There was no library. There was no recreation. There was no employment. Nothing. So you’re sitting in a box for 23½ hours a day, and people went crazy. Literally went insane - we get the word "sanity" as a theme in our thank you notes. People are like, ‘The only thing that keeps me sane is being able to read during this time.’ And I don't think it's always a pandemic, but I think the pandemic was especially bad in that regard.

What do you wish people better understood about the experience of people who are incarcerated?

Prison Book Program: I wish they understood just how dehumanizing it is in there. I have been inside a lot of prisons. I taught classes in prisons. It’s so dehumanizing and that's the point. It's like that by design and on purpose. If we think we're safer because these places exist, we’re crazy. All it does is further harm. It doesn't do anything to heal anything, fix anybody. It’s atrocious and outrageous. That's what I wish that more people knew.

The post Comics for Prisoners: A Roundtable appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment