One of the most rewarding developments of the past decade has been the entirely unexpected return of Casanova Frankenstein, the artist formerly known as Al Frank, to the comics world. (Unexpected for reasons explained in great detail in 2015's The Adventures of Tad Martin #Six Six Sick.) Even better is the fact that, unlike many a “comeback”, Frankenstein’s second act has been no mere rehash of greatest hits, instead seeing him grow by leaps and bounds as a cartoonist and storyteller. Frankenstein's use of his nominal alter-ego, Tad, to explore everything from confessional autobio to poetry comics to nightmare surrealism to punk nihilism has been an eye-opening experience in and of itself for both longtime and new readers alike; but concurrently with Tad’s resurrection, Frankenstein has also released a collection of previously-unseen short strips (In The Wilderness, 2019), and has begun to dabble in “straight” memoir, as well (Purgatory, 2017; The Year I Lost My Mind, 2020). His latest, How to Make A Monster, represents his lengthiest attempt at the latter—or, for that matter, at anything—to date.

Marking Frankenstein's second collaboration with veteran Australian indie cartoonist Glenn Pearce after The Year I Lost My Mind—and the second turn at said second collaboration, given that the pair self-published an earlier version of the same comic a few years back under Lulu’s auspices, the main differences between that and the new Fantagraphics version being a handful of re-drawn panels and the insertion of suitably drab “spot coloring” in many others—there’s no doubt this new 224-page book represents a leap in confidence on the part of both creators, although there are some misfires worthy of note as well. Even with those taken into consideration, however, it’s still very strong, searing work from start to finish, and is well worth anyone’s investment of time and money, so don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good (in fact, of the very good) if you’re on the fence about this one.

What How to Make A Monster most assuredly is not, however, is the story of a monster in the making, despite the title’s unambiguous proclamation. Rather, this book recounts a series of formative experience that occurred in Frankenstein’s life when he was a 13-year old kid in Chicago circa 1980 that almost certainly played a part in his development as an outsider, perhaps even an outcast - but a “monster”? That’s putting things a bit melodramatically, to say the least. In fact, the present-day version of Frankenstein who narrates this tale seems like a pretty decent guy to me, one whose greatest “sin” is as ultimately insignificant as clinging to a punk personal aesthetic long after its expiration date - and come on, we all know a few people like that. Frankenstein might feel like a monster—hence, I suppose, his latter-day nom de plume—but to the level-headed observer from without? He comes off as earnest, thoughtful, and self-reflective. None of the character traits one would typically associate with monstrousness—callousness, calculation, amorality, selfishness—appear to be present and accounted for in this guy in any way, shape, or form. So, yeah - quit being so hard on yourself, Cassie, you’re not a bad person at all.

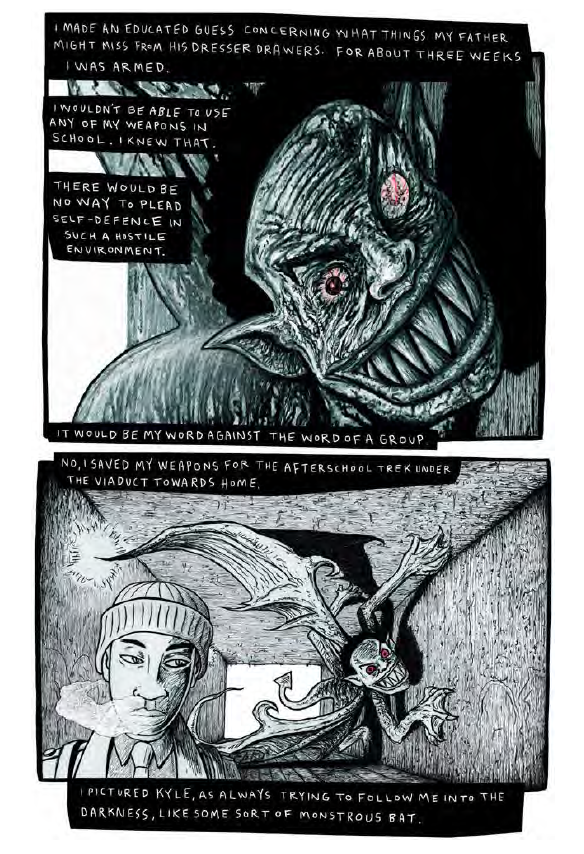

What he is, however, is an alienated person, and what you will find instead in this book is a no-bullshit accounting of the roots of that alienation: noteworthy for its candor, and admirable for the fluidity of its collaborative nature. Pearce plays around with everything from hyper-realistic portrait illustration to chaotic “splatterpunk” art to post-psychedelic dream/nightmare scenarios to gritty urban atmospherics, and it all meshes incredibly well, tonally, with his partner’s script - but to return to my quibble about confidence for a moment, some of the pages are considerably more arresting for their visuals than they are for their narrative quality. For example, the bulk of the “action” here takes place in winter, and while the tone of Frankenstein’s writing is drab, hopeless, and dystopian, Pearce’s art not only matches it pound for metaphorical pound, it actually ups the ante in terms of making you feel the blood in your veins freezing over with its attention to most every detail, whereas a more austere approach, while less visually exciting, would perhaps have dialed things back in a manner more representative of 13-year old Cassie’s defeatist emerging mindset. It’s a small criticism, I won’t pretend otherwise, but small criticisms are really all I have here, so we may as well address the next one, such as it is.

In terms of story pacing, this book is a bit of an odd duck, though it’s hard to call that a “flaw” per se, as it’s entirely apropos of its subject matter: small events are often of outsize import to kids. Frankenstein starts things out with a rather broad and expansive overview of his childhood writ large—abusive, disciplinarian father, distant mother who turns a blind eye to her husband’s behavior, likely by choice—but then narrows in on a couple of key instances for lengthy periods of time, specifically one where a school bully steals his nunchuks (which Cassie, in his turn, had actually stolen from his father), followed by his subsequent decision to start playing hooky, a decision which clearly resonates deeply with him to this day. His class-cutting exploits make for interesting reading, make no mistake—the first time out he whiles away the morning at a shopping mall and covets a copy of How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way he sees in a bookstore display (pro tip, kid: next time just steal the thing, you’re already truant), the second time he lands on the inexplicable-even-by-kid-standards idea of actually turning around and going back home, and is nearly busted by his old man as one might reasonably expect—so the issue here isn’t the narrative value of what we’re reading, but the fact that these arguably benign instances take up so much space in a story purportedly about a child being warped into becoming, well, a monster. It’s a curious way for Frankenstein to spend the bulk of his page count more than it is a grating one, for reasons just mentioned, but it has the unintentional consequence of undercutting the book’s implied central thesis, given its title. As much a heel as this may make me sound, I do have to actively wonder whether or not this work would have come off at least somewhat stronger on the whole if it were simply called something else.

That being said, hey, it’s not my life, nor my story to tell. That’s the responsibility of Frankenstein and Pearce, and they do more than a solid and effective job of it, barring these quibbles. There’s certainly an argument to be made that, in another era, Frankenstein could have gone down a darker path and ended up a school shooter, and that’s a What If? that appears to haunt him in the present, but I think evidence seems to indicate that he turned out as well as he probably could have given circumstances that could most generously be termed dauting, most accurately termed harrowing. A damn good writer—who’s also proven themselves with most other projects to be a damn good cartoonist—came out of that dismal Chicago upbringing, but a monster? I can’t see one from here.

The post How to Make a Monster appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment