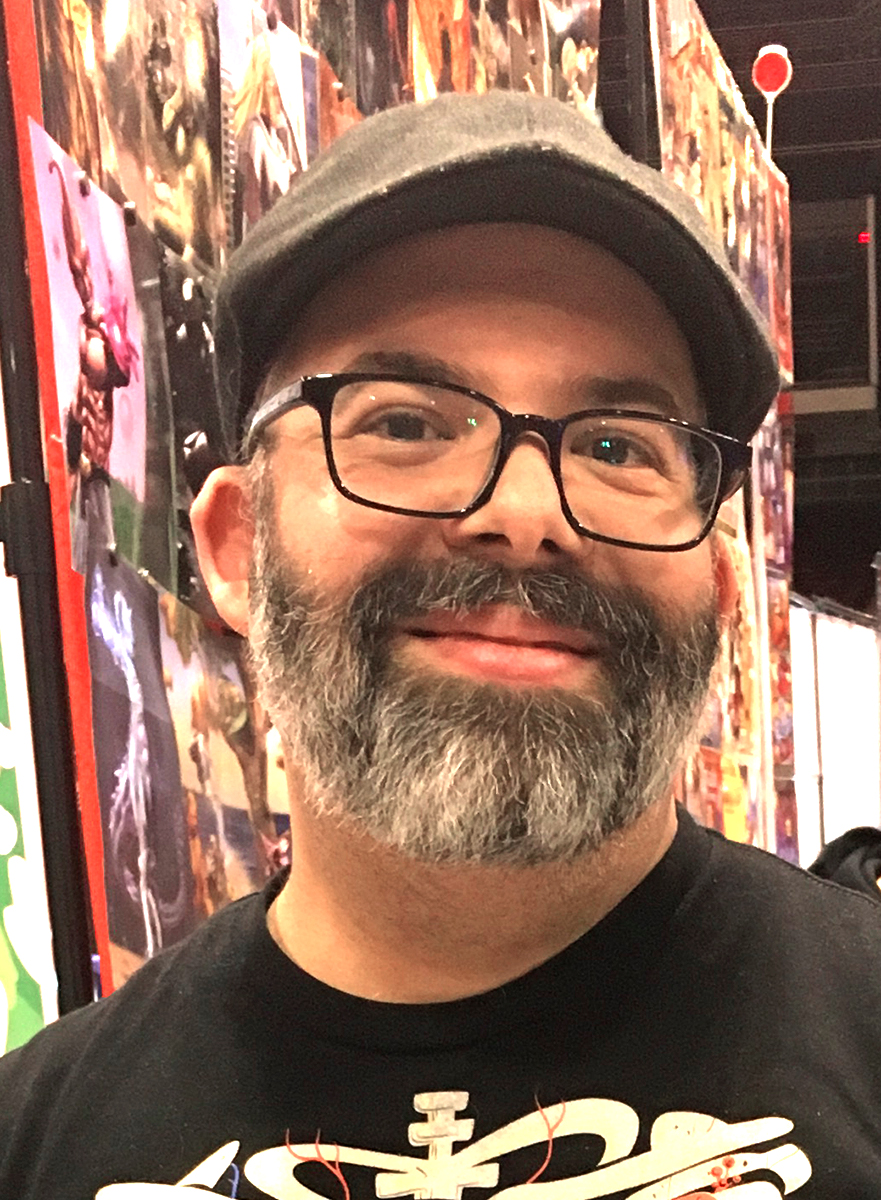

In the 12 years since the start of his first book, The Legend of Ricky Thunder (2010-12), indie cartoonist Kyle Starks has been busy. The creator of popular humorous action comics like Sexcastle (2014), Kill Them All (2016) and Rock Candy Mountain (2017-18), Starks is also known as the writer of dozens of official Rick and Morty comics for Oni Press. We spoke about several of his projects, past and present, starting with a neighborhood house explosion, and ending with Marvel's D-Man.

In the 12 years since the start of his first book, The Legend of Ricky Thunder (2010-12), indie cartoonist Kyle Starks has been busy. The creator of popular humorous action comics like Sexcastle (2014), Kill Them All (2016) and Rock Candy Mountain (2017-18), Starks is also known as the writer of dozens of official Rick and Morty comics for Oni Press. We spoke about several of his projects, past and present, starting with a neighborhood house explosion, and ending with Marvel's D-Man.

-Robert Newsome

* * *

ROBERT NEWSOME: To start, just as a general interest story, can you please tell me about the neighborhood house explosion?

KYLE STARKS: Yeah, a house exploded like five hundred feet away from my house.

I didn’t realize you were that close…

I was so close. I was in the shower. It was during a school day, so no one else was home. I was in the shower and I thought someone had driven a car into my house. So, I jumped out of the shower and put some shorts on and ran outside. Some of my neighbors were pointing and saying “it came from over there,” so I put on shoes and a shirt and I ran down there. This was maybe 7 to 10 minutes after I felt the impact. I got over there and the house was just gone. There was nothing. I actually saw the house next to it first which was half gone. I thought that house had blown up, but no. It was the house that was next to it. It blew up. On my way over there, I thought maybe a plane had crashed.

I didn't realize, when you first posted about it online, that it was that catastrophic. I thought maybe somebody's water heater popped in their garage or something. I didn't realize the severity of it until I read a news article the next day.

The craziest part is how difficult it is to wrap your brain around like how localized the damage was. We had an engineer come out and look at our house to see if there was any structural damage, but there’s a very small area of actual damage in the neighborhood. Looking at what’s left of the house where it happened, it just doesn't make any sense. When we drive by, if you see it, it doesn't make any sense. The house was there and then it was just gone. There was no smoke, no fire… it just disappeared. They're saying they probably won't really know for certain what happened until everyone starts suing everybody.

Is your house okay?

Yeah. One of my storm windows, like the bottom part, maybe, wasn't secured right, and it blew in. I had a single pane window in my basement blow out, but I didn't even notice it until the next day because I didn't look in my basement. The power was out for a while and we lost, really, a single pane of glass. We got pretty lucky, but it was so localized. It's amazing. I go for walks around the neighborhood and you can see the pattern of the blast and how the surrounding houses probably directed it. It's the weirdest thing to me. I mean it's obviously a tragedy because people died, but it just doesn't make sense. If you look at it, it just doesn't make any sense. We just don't see that destruction in life, which, thank god. Let's not start now.

Here's the weirdest part: that’s not the first house to do that. They turned our power off because they had to make sure that if there was a gas leak, other houses weren't going to blow up, right? Smart. So I asked a policeman if he knew when they might be turning the power back on. He said “we don't know anything about that.” I'm like, “this is a weird day for you guys, huh?”and he said “this is like the third one in five years,” which makes us feel real safe.

So, comic books, right?

They’re out there.

That’s what you do. Let’s get a quick background. What brought you to the comics table?

Is this… are we doing an origin story?

We are doing an origin story.

When I was a kid, I was introduced to comics by my uncle Tony Starks. Not Tony Stark. My uncle, Tony Starks, he sold Silver and Golden Age comics and used to write for one of the price guides, he got me into it. I started reading comics really young. When I was a teen, I started working at the comic book store. It was also a movie rental store, and a baseball card store, and a pornography store, and a used music store and a used bookstore. So, I had a world of media to consume for free. It’s a love story. I went to school to be a fine artist and then realized that was stupid. That there's no money there. So I switched to drinking. I got out of comics in the '90s. They were terrible. Well, mostly terrible. It was not an enjoyable time to read comics, I don't think. Then, when I started having kids, I thought “let's make a list of the things that I'll never get to do again.” I made the list. The only thing I can remember on the list was “make a complete comic,” which was my first book, which is called The Legend of Ricky Thunder, which I initially did as a webcomic. I didn't advertise it, didn't promote it. It got picked up by a big website at the time and suddenly people were looking at my stuff, which was weird because I was just doing it to mark it off of that list. But I found out that I really loved making comics. I didn't know that. I really loved the process of it. I still do. I just like telling stories. So I did another one, which was Sexcastle. I funded that one on Kickstarter. I was fortunate enough to have Matt Fraction read it. Matt put me in contact with Image because he liked it so much. And then, it was nominated for some awards, it was optioned, eventually I got a job doing the Rick and Morty comics, and the rest is history, I guess.

It’s interesting that your origin story started in a '90s comics/video/used book store because your work definitely taps into something about that very specific late '80s/early '90s action movie sort of aesthetic.

That’s especially the case with Ricky Thunder for sure. I wouldn't do something unless it was something that I wanted to exist. Ricky Thunder was a wrestling book and there weren’t any wrestling comics I enjoyed at the time. I love wrestling, so that’s the book I made. After that, I thought “I'm going to do the next thing I love, which is '80s action movies.”

I always try to make the thing that I want to exist in the world. Also, I've seen so many action movies. My dad would watch every action movie and he wouldn't care if it was appropriate for the kid in the room, which was me. It’s sort of, you know, “I was born in the darkness,” well I was born in the '80s action movies while others have simply adopted it. That's a comic reference. I don't want to think too hard about it but there is a real sort of '80s action movie structure to a lot of things I do simply because I enjoy that. It's really “hero's journey” stuff, right? That's the type of stories I like. I'm not trying to do high art. I'm just trying to make something entertaining and hopefully good and maybe, you know, potentially great. But I have goals.

The process you described earlier is very familiar to me from talking to people who make comics. It’s a recurring theme that while studying Fine Art, they realized that that's not what they wanted to do and they moved to comics from there. What made you decide that this was where you wanted to go?

I was in college. I was working at a gallery. I was going to be a painter. I was pretty good, but working in an art gallery and seeing people in my classes, I was seeing how there's people who were better than me. I just knew there was no way I could make a living doing this. Ironically, I went to a small school but it had professional working artists on the faculty, and a lot of people I went to school with have become professional artists since then. It’s crazy to me, because the math on that is… the chances are really small. So I thought “I’m never going to make a living doing this, right? It’s going to be so challenging.” So I switched to graphic design. After that, I worked for newspapers, I worked for a pharmaceutical printing company. From college to when I started making comics, it was 15 years. I did nothing creatively during that time. I played bad guitar and drank a lot, that's what I did. I wonder now that I'm older if I could have had the success I've had now when I was younger. I think I was smarter then. I knew more things. I was definitely more well-read then than I am now. But I think when it came time for me to finally start telling stories, I had 35 or however many years of ingesting stories and thinking about stories critically; why I liked them and how they could be better. But I’ve sort of let that go as an old man. So sometimes I wonder how much those years and years of consuming and really thinking about the things I like and why I liked them helped or if I could have done what I’m doing right now 15 years earlier than I started. I don't know if I could have. But I was going to be a painter, which was what my passion was at the time, but it just wasn't realistic for me. So it was another 15 years before I started making comics and certainly longer than that before I was successful at it.

It's interesting that you mention that because a lot of the early comics artists were just doing comics because they wanted to make a living. It's almost the same as what you’re talking about. They were just working artists and could just as easily have been working in advertising, or commercial art, which some of them were doing at the same time.

Fine artist, Robert. I wanted to be a fine artist. With the galleries, you know? I was maybe a little elitist, but never pretentious enough. I don't think I could play the game. Fine Art is a tough world. I don't think about, I don't want to think about the Fine Art world. I'm not doing it. When I get old, I’ll just go out and paint in the garage; make pop art text pieces like I did when I was 18. That’ll be me as an old man.

The experience of having your work optioned is one that happened pretty quickly in your comics career. Can you describe that experience?

I had done, I think, two Kickstarters, which were Ricky Thunder and Sexcastle. Then Sexcastle came out from Image. I think at the time I was working on Rock Candy Mountain. I got an email through my Storenvy site, and it was someone from the William Morris Agency. Well, immediately, I thought it was fake. It can’t be real because that's not how to contact me. They would send me an email or even a DM on Twitter or something. But not through Storenvy. But I replied to it, and it was not fake. They sold the rights to Sexcastle before it came out from Image.

With your first option, you’re sure something’s going to happen. It's the greatest moment. We joke in my house about how rarely I really show excitement. I have diminished expectations for everything. I got really excited about this. My kids were going to a Lutheran school at the time and my daughter said “I can't wait to tell kids at school that my dad's book Sexcastle is being made into a movie.” And we're like, “you're not allowed to say that at your elementary school.” Nothing really happened with that, though. Then Kill Them All was optioned. Nothing has happened. Rock Candy Mountain was optioned. Nothing has happened. Everything else is in discussions right now.

Selling the rights to something is better than getting optioned because you get more money, but they get to keep it for longer. It’s nice. When things get optioned, it’s really nice to have a little extra money, but that’s all it is. It’s not a lot of money. Maybe someone out there is getting a lot of money for their options, and if they are, good for them. I’m not. But it’s always very nice. It would be great if something happened with these options but I have no expectations now, as opposed to the first one when I was jumping up and down.

It’s a part of the industry now. I remember when I first got into comics every [prose] novel was optioned. That’s just how it was. Every publisher had some kind of connection to some film company. I think comics are basically there now, too. It’s just part of the industry. That sounds like a real downer for something that should be exciting. When people tell me they’re hoping for something they’re working on to get optioned, I mean… it makes sense because it’s probably more money than they’ll make from the comic, especially if you’re a writer, but it’s not that much money. Don’t get me wrong. It’s nice. Someone’s going to read this and think “wow, this guy’s just a bad negotiator.” But until they make something, it’s not that much money. I remember telling people about it when the first one got optioned. I think I wrote about it on Facebook or something, and people were like “oh, now I know who to ask for money.” It’s not that much money, dude. I’m going to be able to pay my bills for three months, you know? But it’s nice. That’s a nice three months.

I’d like to think that at some point something’s going to catch. That will be thrilling. I can’t wait for it to happen. Most likely it will be the book I like the least. I suspect that’s how it goes for everybody.

Was it a difficult jump from working on creator-owned material to working on licensed properties?

Sort of. Sexcastle was nominated for Best Humor Publication. That was my first Eisner nomination. I think the way it works in comics is that if you wrote something that was funny, then everyone who has a funny book is going to get in touch with you. That’s kind of what happened. The first book I did was Invader Zim. I’d just done Kill Them All with Oni and they asked if I wanted to work on Invader Zim. I don’t know anything about Invader Zim. I’m too old for it, really. But they said that’s what they were looking for; they wanted fresh eyes on the book. I watched all the Invader Zim cartoons in an airport in Portland on my way home from the Rose City Comic Con, and there were things that I liked about it but it’s definitely not made for a man in his 40s. I did an issue and it turned out that “fresh eyes” was actually not what they were looking for at all.

I remember talking to my wife and saying “I really wish they’d asked me to work on this other thing,” which was Rick and Morty. I know this is hard to believe, but at the time, nobody knew what Rick and Morty was. This was between seasons one and two. I only watched it because I love Dan Harmon’s work on Community and The Ben Stiller Show. I remember seeing the trailer on Adult Swim and thinking “boy, that looks so poorly drawn,” you know? But I really enjoyed the first season. So, they asked me if I wanted to take a shot at it. I started by doing five issues of the Rick and Morty comic [beginning with #16, July 2016]. I liked working on it. It’s funny, it deals with a lot of different storytelling tropes. Writing Rick and Morty was not hard. I was supposed to do five issues and I ended up doing 48. They just kept me on until I didn’t want to do it any more, and then we killed off the main series at issue 60, which was right around the beginning of the pandemic. I loved working on that book. I loved working with those characters and I think recreating an established voice is something that I can do pretty well. I take a lot of pride in my work on that book.

I did Mars Attacks [with Dynamite Entertainment] later. They got in touch with me because I was working on Rick and Morty and so now I’m writing a funny science fiction book, you know? So they got in touch and I told them that I’d never really seen the cards and I don’t really have a lot of knowledge about the story. I mean, I liked the Tim Burton movie when I was a teenager, but I was a dumb teenager. But they sent me the cards and the cards tell a story that sort of escalates as the series of trading cards goes on, so I had the idea of a reconciliation story between a father and son against the background of the Mars Attacks events. I was talking to my friend Chris Schweizer who has colored almost all of my stuff. Chris is my best friend. He said: “That's a great idea. Tell them I’ll draw it,” which is not how it works. You don’t just get to call your shots. I mentioned it to my editor, kind of as a joke, you know “ha ha, Chris Schweizer says he’ll draw it,” and he said “I love Chris. That’s a great idea. Let’s do it.” That’s not how it works. That’s not how you get into comics. So, Chris drew it. I think that’s one of my better books. I feel like I was able to capture the voice of the story in the cards while doing something different with it.

Do you have a different approach to your work when you’re just writing as opposed to when you’re writing and drawing?

The biggest difference is that I would never ask an artist to do on a page the things that I would do on a page. I’m working on something right now, expanding something that I put out for Free Comic Book Day a while back, and I have 10- or 12-panel pages just left and right because that’s what’s needed for the pacing I was going for. I would never, as a writer, ask an artist to do that. So my way of storytelling may be a little different when I’m collaborating. I want to make sure the person I’m working with gets some form of joy out of the project, even if it’s work-for-hire. I also don’t write scripts for myself. I think about this stuff so much, so it’s kind of the same, but even if I have everything in my head, I don’t like to use a script. I like a bit of improvisational energy. I’m sort of a dialogue-first writer. So, I tell myself the story over and over and as I do that, bits of dialogue will start to form.

You’ve had a lot of success on Kickstarter. What, in your mind, are the advantages of that platform? It almost seems like now that you’re more established, you could step outside of it and just do your projects yourself.

After I did Kill Them All through Kickstarter, I really thought I wasn’t going to use the platform anymore. I love the idea of crowdsourcing. I like the feeling of having some sort of interaction with everyone who’s buying one of my books. I like the idea that people who are buying my books are getting a little bit more than what they’d get if they bought it in a store. I like that social interaction. When I started, that was the only way I knew how to do it. But I started doing Rick and Morty and thought that I wasn’t really going to go back to that sort of method. I had built up a little name recognition and I didn’t want to overshadow someone who maybe could benefit more from the crowdfunding process. But with crowdfunding a book through Kickstarter, I have a bit more freedom. There’s no editor. It’s just me. I went back to Kickstarter for Old Head [2020]. I keep getting drawn back to that feeling of a one-on-one interaction between me and the people who are supporting the project. It’s one of the healthiest experiences, mentally, that I’ve had in comics.

Is it beneficial, though, to go through someone else’s platform, or do you think you could replicate that experience without using Kickstarter or any other crowdsourcing platform’s infrastructure?

You know, I’ve never really considered it. With Kickstarter, specifically, there’s sort of a built-in audience. I don’t really know if that’s true right now, but before the pandemic kicked in, at least, there was a built-in audience there. So, let’s say I sell 300 books. Maybe 100 of those are just people who just shop for comics on Kickstarter. The platform encourages that sort of repeat shopping. There’s a benefit to that. I’m not sure if everyone who bought a book from me through a Kickstarter campaign would have bought that book if I had self-published and sold it myself. Kickstarter, by nature, is temporary, though. A publisher can establish that sort of back-catalog where it will exist for years and years, but on Kickstarter, six months after a book comes out, everyone has moved on.

I also wanted to talk to you about D-Man. What’s the deal there? What’s your fascination with D-Man?

Okay, how long do you want this to be? You can’t have me talking about D-Man. We don’t have time or space for this. Here’s the story with D-Man. He’s fucking great, and no one knows it. He originally appeared in The Thing [#28, Oct. 1985]. He was the champion of the Unlimited Wrestling Federation. If my facts are wrong, I apologize, but I know they’re not. D-Man was Ben Grimm’s best friend and these wrestlers were all doing muscle drugs. That’s how they got their strength. If they didn’t get these drugs on the regular, they would go into withdrawal. The guy who gave them these drugs was called the Power Broker, which is a good name for someone who gives people power, right? They wanted D-Man to betray Ben Grimm but he was such a good friend that he refused. When he refused they were like “okay, no more drugs for you.” Ben Grimm found Dennis “D-Man” Dunphy in the fetal position, with his giant muscles, on the bathroom floor and he’s crying because he’s in withdrawal because he wouldn’t betray his friend. That’s great. This guy who will literally suffer instead of betraying his friend? This is my guy. I love D-Man.

D-Man showed up in the Mark Gruenwald Captain America run. I love Gruenwald. I’m a Gruenwald boy. I believe with all my heart that if Gruenwald could have written dialog 1/7th as good as he could come up with superhero stories, he would be considered one of the greatest of all time. His stories were so good. His dialogue is so not great. At one point, Captain America went missing and D-Man, Nomad and Falcon teamed up to find him. Nomad was kind of cruel to D-Man because D-Man is kind of simple. But D-Man’s whole thing is that he loves Captain America. D-Man is so sweet and loyal. It’s great. He gets punched off a cliff by, like, Titania or some D-level super-strong character and the next issue, he has to confront them and he hides because he doesn’t want to get punched again. Which is natural! D-Man was using his money from when he was champion to fly everyone around and look for Captain America. He used his money to take care of homeless people, which eventually got turned into a joke by Marvel that D-Man was homeless. I hated that. The joke was that he was a homeless, stinky guy. Nope. D-Man just wants to take care of people.

You can find a lot of D-Man art by me online. I wrote what was, at the time, the only dedicated D-Man story in comics history for Secret Wars Too [2015], drawn by Ramon Villalobos. Then Nick Spencer did one right after that. I think D-Man is just so human, you know? He’s just a regular guy who cares about people.

The post “You Can’t Have Me Talking About D-Man”: An Interview With Kyle Starks appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment