Originally posted, with slightly different formatting, to the online edition of The Comics Journal from February 16-19, 2010. Some images differ.

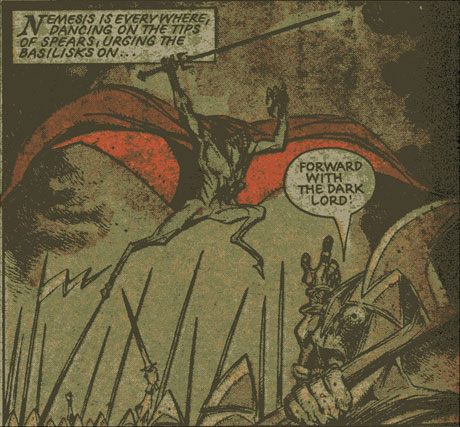

Occasionally, the parts of the comics industry that are designed to produce mass entertainment nurture an artist who’s not just a first-rate entertainer but genuinely freaky. It helps if that artist has as much of a taste for baiting censors as Kevin O’Neill does. O’Neill was hired by the British publisher IPC at the age of 16, and worked there as an art director in the early days of the long-running weekly sci-fi anthology 2000 AD. He quickly developed an explosively weird style, all jagged lines and beveled edges, and with his longtime collaborator, writer Pat Mills, devised an appropriately bizarre showcase for it: Nemesis the Warlock, whose hero was a demonic, horse-headed alien.

Mills and O’Neill continued their association with 1986’s Metalzoic — essentially an extended excuse for O’Neill to draw gigantic robot dinosaurs, published around the time O’Neill had the curious honor of being the only artist ever to have his drawing style decreed unacceptable by the Comics Code. There had always been a touch of comedy about his work, which flowered in his next collaboration with Mills: Marshal Law was a bloody, bloodthirsty satire of superhero tropes, set in a dystopian future San Francisco. Initially an Epic Comics miniseries, Marshal Law appeared between 1987 and 1998 in various serials and one-shots. (The long-promised Marshal Law compendium is currently scheduled to be published by Top Shelf in December of this year.) - (Marshal Law was eventually collected by DC Comics in 2013 and 2014; both editions are currently out of print, although a digital version remains available. -Ed).

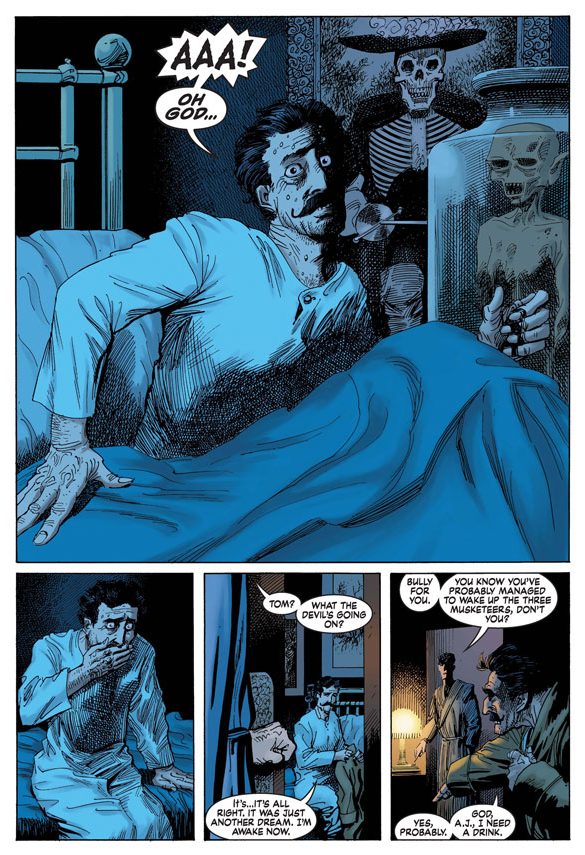

For most of the past decade, O’Neill’s been drawing a series that shows off his gifts for dramatic pacing, fuming caricature, stylistic pastiche and outlandish invention: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a cracked rampage through the history of pulp fiction. Written by Alan Moore, it’s run intermittently since 1999 (and inspired a disastrous 2003 movie), and has featured some of O’Neill’s most uproarious and thrilling artwork. (As with his idol Will Elder’s work, every reading reveals new details to giggle over.) The 2007 League volume Black Dossier, in particular, is a visual tour de force, with its narrative sequences punctuated by spot-on parodies of vintage British boys’ comics, Art Deco, Tijuana bibles and more, culminating in a flabbergasting psychedelic 3-D freakout. O’Neill is currently working on a League project called Century, whose three volumes are set in 1910, 1968 and the present day; the second volume is due from Top Shelf in October. I spoke to him via phone in August, 2009.

-Douglas Wolk

* * *

DOUGLAS WOLK: Tell me a little about the comics you read in your early years — you’ve mentioned looking at a lot of Ken Reid stuff.

KEVIN O’NEILL: When I was a small child, I was mainly reading the popular British comics like The Beano and Dandy — the DC Thomson-published comics. They were the most vibrant. There were a lot of exciting artists — Ken Reid, Leo Baxendale, Davey Law, and Dudley Watkins. They did the principal strips in those two comics. I was a huge fan, as well, of the Fleischer Popeye cartoons. This was long before I ever saw the strip, but — there’s kind of a theme here — I was a fan of the offbeat-looking characters. Then I stumbled into American comic books — this would’ve been in the late ’50s or early ’60s, when they were very patchily distributed in Britain. They’d come over as ballast, essentially. So you could never follow a complete run of anything; you’d just get these odd outcrops of DC and very early Marvel stuff. There was all of that, and we had this weird holdover from the Fawcett comics period, when they were reprinting Captain Marvel in black-and-white comics, and Tarzan strips, as well, and they were still being distributed long after they effectively went out of business. There must have been warehouses of them, offloading them into London shops near where I lived. So I was seeing all that stuff. I think people of my generation — I was born in ’53, but me and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, we all grew up in a strange patchwork of British and American material. It was an interesting time. You had to kind of search around to find it — it was kind of a treasure hunt, looking for material. All that made me want to draw, and I suppose what I really wanted to do was grow up and draw Batman. I read the Batman stuff in those old 80-Page Giants — the Dick Sprang stuff, which I liked a lot: the distorted or expressionistic material.

But I think the big thing in my life, and I think for a lot of people of a similar age to me, was seeing MAD paperbacks, reprints of the early comic-book MAD stuff. I absolutely adored them and went to great lengths to find the other books in the series, all that fantastic Bill Elder and Jack Davis and Wally Wood art. I went to a strict Catholic school: all comics were effectively banned, but American comics were seen as particularly pernicious. MAD, by title alone, at a Catholic school — you got beaten if you were caught with a copy. It was a serious offense. It did make it all the more beguiling, like anything with a prohibition on it. I’ve talked to friends who grew up on this stuff, a lot of MAD we didn’t understand, because by its nature it was a Jewish sense of humor. But it was a kind of window into a fallen, fascinating, cynical adult world. There was no British equivalent to that, really. Our comics were bizarre or featured teachers and park-keepers and those kind of authority figures who were the butt of jokes. I’m not sure there’s exactly an American equivalent to that — there’s not quite the same loathing of teachers and headmasters, and the conceit of the mortarboards and the spats and the gowns and all that, decades after they’d vanished from regular schools. But it became iconic imagery, and the caning and all that corporal punishment stuff was a big part of British humor comics. All the spanking and caning — there’s almost a logic to it that leads ultimately to Judge Dredd, in a way. It’s a very important moment when you’re a kid to see the pomposity of adults punctured — it’s every child’s fantasy. But it got me excited about comics, all these different styles, and principally in the early days it would’ve been the humor material I loved a lot.

I’ve seen some pages of a horror comic you must have drawn in the early ’70s.

I worked for a poster magazine series called Legend Horror Classics, back in the ’70s, before 2000 AD — one of the things I showed to Pat Mills to get a job at 2000 AD was a Jaws rip-off I did. The poster magazine format was a big poster with a comic on the back — pretty primitive, but I liked horror material, and I liked humor. By the time I was doing that, I’d been on staff from the age of 16 at IPC Magazines, as an office boy and gofer. I’d worked for the art department, and coloring department, and so on, doing a lot of paste-ups and stuff like that. It was very difficult in those days to break into comics, because British comics before 2000 AD had these very rigid house styles. If an artist’s style was popular, it was replicated by many imitators. No one signed their work. One of my first jobs in comics was whiting out artists’ signatures. I did ask why I was doing this — it used to frustrate me as a kid not knowing who did certain strips. And I was told, in all seriousness, that if the reader saw a signature on a page they wouldn’t believe it was real. It’s like a director’s name floating across the corner of a cinema screen or something.

The real reason was credits gave the creators tremendous power. And they were worried about their rival, DC Thomson, poaching artists and writers. They did treat their contributors like ... rather tall children, if you know what I mean.

This kind of house style look was very commonplace. Leo Baxendale, who was one of the most popular humor artists, had numerous imitators throughout all the different stages of his career — they were imitating Leo Baxendale in his 20s, or Leo Baxendale in his 40s. Likewise, the adventure stuff — there were many, many imitators of the popular adventure artists, but occasionally you’d get people like Frank Bellamy, who would just do work that no one could credibly imitate. We had these fantastic artists. Often the writing was a little on the poor side, shall we say. We hit a wall early on with 2000 AD — you were told your target audience was no older than 12, but their idea of a 12-year-old was a kind of Enid Blyton 12-year-old, this kind of kid who hadn’t really seen anything or done anything much and lived in a narrow, small world. There were lots of serials that ran on for months and months, with bigger and bigger recaps every week — it was well overdue for a change. When Pat Mills and John Wagner came along and did Action and ultimately 2000 AD, it kind of changed everything. There wasn’t anyone else with their talent to carry what logically should’ve been an expansion of British comics, and now most British talent goes to America to look for work. It’s a shame, because we had this fantastic industry once — the newsstands were full of British comics, and it was quite fascinating, as a kid, to see the variety. It’s such a different world now.

You were the second art director of 2000 AD, right?

Yeah, the original art editor was in fact the person who taught me a lot when I went in there as a 16-year-old — I was in my 20s when 2000 AD started, but when I went for a job at IPC and saw managing editor Jack Le Grand, and Valiant editor Sid Bicknell. They introduced me to art editor Janet Shepheard, and she was a brilliant art editor. In fact, she designed a lot of logos for Valiant and other comics — she designed Judge Dredd’s original logo. I learned a lot working with her — she was the safe pair of hands on 2000 AD who could fix anything. When she was transferred to Starlord, which was a kind of 2000 AD doing a rip off of itself, her job was offered to me, so I became the art editor. By this point, Pat Mills had left. Me and Nick Landau, Colin Wyatt and Robert Preston had it to ourselves to play with — there weren’t many eyes on us. The relationship with management when we were doing 2000 AD was kind of cat-and-mouse — we had to sneak stuff through. They knew what we were up to; they weren’t too happy about Judge Dredd saying “drokking” and all that kind of stuff. They knew they didn't like it, but they couldn’t quite pinpoint why they didn't like it. As long as it was making some money, they were happy enough. But eventually there was someone put in place to censor us — that led to head games, trying to get stuff over on him. We knew we had an older audience than 12-year-olds at 2000 AD, but we were constantly hammered with “it’s for kids, it’s for kids, it’s for kids.” It was kind of frustrating, and ultimately why I went freelance. I’d been doing bits and pieces of artwork for 2000 AD, but I decided to go freelance.

When would that have been?

2000 AD was in preparation in 1976, but came out in 1977. I think ’78 was when I started freelancing for 2000 AD, doing Ro-Busters, the robot strip that me and Pat Mills worked on. That was great. We had a fantastic time — we could more or less do what we wanted. I’d do a couple of episodes, then Mike McMahon would do some episodes, then Dave Gibbons would do some episodes. That eventually grew a spin-off, the ABC Warriors, which was much more popular. I did a couple of episodes of that, and then there was a lot of trouble in the office with censorship and aggravation. And I’d been offered a job at Pinewood Studios doing storyboards for a Gerry Anderson film that actually ended up never getting made, called Five Star Five, so I worked there briefly on that. Which was ... an experience, but storyboarding was not my favorite thing. I preferred design work.

Eventually I went back to freelancing for 2000 AD, and Pat and I created Nemesis the Warlock, which was probably the most fun I had on 2000 AD. We just went crazy — Pat’s an ex-Catholic like me — a Catholic upbringing, with all the nuns and the beating — in a way, Nemesis is a natural outpouring of bile against all that. When we were preparing it, there was an alien hero, and the villains were human. To make them transparently obvious that they were evil, we decided they should be in Klansmen and Inquisition robes. We had a lot of fun, but a lot more in the way of censorship problems with IPC.

That was a strip they really didn’t like — and probably with just cause, because we were always up to no good. It’s very very cruel — it’s poisonous, in a way, and bizarre as well. I’ve been looking over reprints of that stuff, and seeing Nemesis ride around on his wife’s back, who’s like a centaur, is pretty strange. It’d be strange in a Vertigo comic! But it was pretty strange back in the early ’80s. It was incredibly popular; as long as it’s popular they kind of leave you alone. They were never happy about it: there was always a feeling on the floor of IPC that this was kind of rocking a boat. We were constantly, in the early days of 2000 AD, experimenting and trying different things; some things worked, some things didn’t. We had terrible printing — the paper was absolutely godawful in those days, and color repro was shocking, but we worked as hard as we could to make it lively. When Pat and Kelvin Gosnell were preparing 2000 AD, they were using — (because at the time they couldn’t find British artists to do many of the strips) more and more foreign artists, but they still couldn’t quite get the look they wanted. When I started, I made them aware that there were people like Dave Gibbons out there. I knew Dave from a bit earlier — most of us had been doing fanzine work when we started. And we got Dave, we got Brian Bolland, we got Mike McMahon — a lot of people walked in the door. It was right place, right time — the planets lined up and we got all these incredibly talented people. And it worked out beautifully, I think.

Looking at your 2000 AD work, as soon as you started drawing Nemesis, from that very first story, the “Terror Tube” story, your artwork really became very much its own thing.

The big breakthrough for me was that with the earlier stuff, you were very aware that you were sharing these characters with other artists. It was a shared experience. But with Nemesis, they were going to give me enough time to draw it all, and I kind of hit the ground running. I just loved it. I loved the idea of what we were doing. By that point, 2000 AD was very popular — if I went out with my wife anywhere, to parties and things, it was quite astonishing how many adults were reading it. They always said the same thing: They didn’t buy the first three issues, because the free gifts attached to the front cover made it way too embarrassing, but they picked it up later and it had this kind of interesting cult following. Judge Dredd was, of course, hugely popular ... but yeah, it was great.

There just came a point later on where it suddenly became not so much fun anymore dealing with all the management issues. They did seem inclined to want to kill the golden goose — there were lots of threats, and the knockoff Starlord, which was a kind of better-printed imitation of 2000 AD that Kelvin Gosnell edited. It had some great stuff, and Ro-Busters began in there, and Strontium Dog began in Starlord. In British tradition, when something folds, it folds into another publication, and becomes a double title for a few months — it was “2000 AD and Starlord.” But the rumor was that the management hated 2000 AD so much that they were going to do it the other way around, and crush 2000 AD into Starlord. I think the bottom line was our printing was cheaper than Starlord’s. And I think, secretly, we did sell more copies. It was an exciting period. Pat had another strip which he showed me notes for, and that was Metalzoic.

That would have been ’82, ’83?

Yeah! He showed it to his wife at the time, and she said “this is too good to give to them,” because it was one of those all-rights situations back then, with no royalties, no nothing. And IPC had often reneged on deals — I think Pat was promised a cut from the creation of 2000 AD, which he never got, et cetera. So he sent me a synopsis, and I thought it was fantastic. What had happened was that 2000 AD had caught some Americans’ eyes. I think Mike Gold might’ve been the first person to write anything about 2000 AD in the fan press, and Marv Wolfman and Len Wein noticed it as well. DC were looking to poach Brian Bolland, who was a huge Silver Age DC fan, and also Dave Gibbons. That was going on, and then they sent Dick Giordano and Joe Orlando to London to look for artists — I think they were looking for artists for Superman. They interviewed a whole bunch of us, and I started doing filler strips, Green Lantern Corps stories, the Omega Men, stuff like that. And Andy Helfer was editing the Green Lantern book, I think; they didn’t quite know what to do with me, because when they asked me “what characters would you like to draw,” I gave them a list of things like Blackhawks and Plastic Man. They said, “How about anything we still publish?” I think the Spectre was another one.

And Pat and I were doing Metalzoic — it was going to go into a new British publication under a different title, a comic/magazine hybrid called Look Alive. That folded after, I think, just three or six months, before we got anywhere with it. So we offered it to DC when they were doing those odd-format graphic-novel European-style books — The Medusa Chain, The Hunger Dogs ...

Me and Joe Priest...

It must’ve seemed like a great idea at the time to do European-style format, but I think it didn’t actually fit on any American shelves! We had the misfortune that when ours came out, it was within weeks of Frank Miller’s Dark Knight, and I think Dark Knight became the format of choice. We had this very very weird robot book which did horribly — it didn’t do anything — I think it’s better known for its later reprint in 2000 AD. Oddly enough, whenever people ask me about that book, they say when are you going to reprint it? And DC will never allow it to be reprinted. It’s one of those things that’s completely fallen off the radar. There’s a few hardy souls who liked it.

Do you own any of the rights to it?

That’s the first book we ever had a contract on, so back in those days it seemed very exciting — we would have gotten a royalty over a certain number of copies, and we got guaranteed credits, and the artwork was returned — many things which weren’t anything like the way British publishing treated us. But the underlying contract in those days was so primitive — effectively, DC own the book, so we can’t take it anywhere else or do anything else with it. It’s in DC limbo. Which is a shame — it’s one of those things that I’d like to see out there again.

Between ’83, when you sort of tailed off work on Nemesis, and ’86, when Metalzoic came out, were there other projects you were working on?

My way of working with Pat Mills on 2000 AD was kind of free-form — the editor would have an outline of what we wanted to do, and if it occurred to us we’d go off on a tangent and take it somewhere else. Working with DC, they wanted a very rigid plot, and it had to be what it had to be. We did Metalzoic, and then we did a thing for IPC called Dice Man — which was a role-playing book, which was a colossal amount of work, more work than we’d really anticipated. But we did that, and it drove us nuts. Everything about it was a pain in the arse. By this time, Metalzoic had come out and flopped, and Dice Man didn’t work either, so we were heading for a three-strikes-you’re-out kind of feeling. That’s when I said to Pat: well, I’ve doodled these notes and sketches for Marshal Law — just a character design, nothing else.

We could’ve offered it to DC, but by this point I’d met Archie Goodwin. Archie was one of the nicest people in the whole industry, a fantastic character who did a lot of great work, much admired by us. The Epic comics thing was going on, and that seemed like a good fit. The Marshal Law we offered Archie was much more Road Warrior, much more Mad Max. He warned us that Marvel famously takes a long time to do paperwork, and so a year went by. Which was a lot of time to think about this, and Pat, who didn’t grow up with superheroes and has no affection for them, was looking at what we’d done, and he said, “Well, why don’t we make the character a superhero hunter?” And that was really the turning point. We offered that to Archie, and he was terrific — he just let us do it. It came out in ’87, and Marshal Law was a hit, thank God. We got the same kind of kick that we got off Nemesis the Warlock — we were just laughing all the time. The more cruel we were, the more we laughed. It did cause occasional friction ... but Marvel were astonishingly good-natured! They didn’t mind at all what we did with their characters in pastiche or parody form.

DC seemed a little bit more priggish, shall we say. The one that caused the most problem for me was the Secret Tribunal book — I rang up Pat, we were about to embark on a new adventure, and I said, “I’ve just been sent the DC Archive of the Legion of Super-Heroes, who I always fucking hated as a kid. I absolutely loathed them. I loathe all that Silver Age kind of good-for-you ... I liked the Kirby and Ditko stuff, but I couldn’t get into the Silver Age DC stuff. But I was a fan of Gil Kane and Carmine Infantino and a huge fan of the old Bizzaro World series.” So I was looking at this, and I thought “this is appalling”, and I sent it to Pat and he laughed his head off at it. So we did our Legion of Super-Heroes, and I was very surprised when we were taken immediately off the DC comp list! “If we’re going to send up anything else of theirs, we have to buy it.”

I want to go back a little bit to the beginning of Marshal Law and how you worked up the look of it and the setting of it. Had you visited San Francisco?

No! At that point, I’d only been to America once — I went to New York and met Archie Goodwin. That was about it. Why did we choose San Francisco? It just seemed like a visually exciting city which was kind of underused in comic books. The look was partly because Epic comics were on such good paper — they had such great repro that there was a possibility of doing painted full-color artwork. One of the beefs with Metalzoic, which I colored, and the color was absolutely terrible, was the way it was done, which was blue-line. I had to resort to something I’d been taught back in my old IPC coloring department days: mixing paint with soap to get it to stick to a surface of a blue-line. It was time-consuming, and it was absolutely terrible. Jesus, it was an embarrassment. Ugly as sin. So for Marshal Law, I thought “I’m going to color the original artwork and get proper reproduction.” That determined part of the look, and I was working with marker pens to get some sort of speed and some sort of output on the book. I think the early ones are pretty primitive, but by the time we did Kingdom of the Blind I was confident with the finished result.

When I look back on it, it seems slightly demented — it’s so bombastic and operatic, it’s hard to know what to make of it. I know some people liked it a lot when it came out, and some people in the industry detested it and didn’t like the way it treated iconic superhero images and so on. Not that we cared! [Laughs.] But it was tremendous fun. I think in the Epic period there was only one page you’d call censored. They asked me to alter what we liked to call the “flying fuck” sequence, which featured the Public Spirit and his girlfriend — they were originally naked, and it was either Archie or Dan Chichester, the editor, who said the women in the office were very unhappy with it. So I pasted a cape over them. I did it to myself on that one. There’s only one other example in Law I can think of which was censored, one of the Dark Horse books — I think it’s the Mask crossover. We often refer back to the red light district in San Futuro, and on my original I had in the background, one of the shop fronts with “Pussy Palace” on it. But someone in the office changed it to “Pushy Palace”.

Yeah, I remember seeing that and thinking “that doesn’t seem right ...”

It kind of scans in some sort of bizarro way. The spirit is there. It’s a very odd thing to do — I guess somebody was uncomfortable with the word, but they didn’t say anything to us. But given that there must be 600 pages of Marshal Law, and those are the only two examples, it’s a very low rate of attrition compared to our previous experiences. [Laughs.] It got more and more difficult with Marshal Law to find a publisher who was prepared to pay for full-color artwork. The last couple we did were the black-and-white ones, the Savage Dragon, which was great — Erik Larsen’s a terrific guy, he let us do those books and we had a lot of fun.

It looks like Law in Hell actually came out between the two issues of Secret Tribunal.

Law in Hell was the Pinhead crossover. Me and Pat did a signing tour of America in the era of multiple covers and embossed covers, and the whole industry seemed set to collapse. We were crossing America, and it felt like there were waves of comics stores folding all around us — we thought, Jesus, things are pretty rough out there. By the time we got to the Savage Dragon crossover, they couldn’t justify doing color, which was a shame. But I believe it’s going to be colored up for the Top Shelf reprint.

Marshal has a strange trajectory through our work. We always loved doing it — the people who like it like a lot and the people who hate it hate it a lot, and we get just as much out of hearing the people who hate it complain about it! [Laughs.] But they often won’t rise to the bait if they know we’re enjoying it, you know what I mean?

There were a few of the Marshal Law books where you were turning over some of the work to other people — Marshal Law Takes Manhattan is the first time I’d seen you inked by somebody else.

Originally that was going to be a legitimate Marshal Law/Punisher crossover. Pat kind of balked at being hemmed in by it being the real Punisher, and Marvel said, “You can do your own version of the Punisher, we don’t mind!” So we did the Persecutor, which we had a great time with. But they wanted a book out very, very quickly, so they got someone to ink it and a colorist. I think originally it was going to be Tom Palmer, but Tom was busy. They also asked Al Williamson, curiously enough, Archie was going to call in a favor. I think it turned out well with Mark Nelson, but I always prefer inking my own stuff. I’ve only been inked by other people twice — Bill Sienkiewicz inked something I did for the Epic superhero line, Critical Mass. I did some covers for them as well, but there’s only one issue where I penciled it. It was a very weird, mondo bizarro combination. I always prefer inking my own stuff, because it seems like the amount of work it would take to do detailed pencils for someone else to understand, I might as well ink it anyway!

What happened with Apocalypse? The Hateful Dead ended on a cliffhanger, and then Dark Horse took over a year later.

That was a British publisher, Geoff Fry — his dream was to do a British weekly like 2000 AD. I did a cover for a fanzine that Geoff was publishing, and it sold rather well — he got in touch with me and asked, “Is there any chance of doing a Marshal Law book?” That was when things were going a bit wonky at Epic — by this point Archie had left. We looked at our contract, and we could take it back, and Marvel were cool on it — we got the rights back in a straightforward manner. We wanted to do a monthly anthology comic — we kept saying to Geoff, “A weekly’s a nightmare beast of a thing for a startup publisher to do.” But he had his heart set on it.

The Marshall Law one-shot Kingdom of the Blind was a prelude to the launch of the weekly comic Toxic! Our royalty money from Law was pumped into the weekly and so began a fucking nightmare. The principal creators were all friends from 2000 AD and between disagreements on content, payment slowdowns, work being late and Pat and I having to run interference to hold the thing together as best we could, factions began falling out with each other. Never — never go into business with friends — especially on a creator-owned project where anyone can withhold work and wreck everything.

It was a kind of mesmerizing shambles. It had a fairly good run — it was interesting, and we would’ve loved it to have worked — a lot of energy went into it. It was a period of a lot of new comics coming out in Britain, the last big gasp, really: we had Revolver, Blast!, Crisis — all these things where people were trying to find new ways into the market. They ended up bombing — just fell apart. Again, we had the rights back to Law, and we finished the second half of the Toxic! story with Dark Horse.

We did offer Law to DC once — in fact, we offered it to them twice, and the first time the person we offered it to ... I once described it to someone as “like putting toxic waste on their desk.” The reaction couldn’t have been more horrified, frankly. [Laughs.] We’ve had lots of interest from movie people over the years, and last year it got probably closer than it’s ever gotten before — McG was interested in doing it after he finished up Terminator Salvation, and Rich Wilkes, the screenwriter, who’s been talking to us over a number of years, said he’d like to do Marshal Law. By coincidence, I was in California on holiday, and this thing had blown up, George Clooney’s company were interested, and the Rock, and Disney of all places, which was the most bizarre one to us — we did kind of toy with the idea of Marshal Law going to the land of Mickey Mouse. The McG thing was advancing, and I’d stayed on a few days to attend this meeting in the Warner Bros. presidential boardroom. And I thought, “If DC knew this, they’d be mortified.” Then the whole thing fell apart — this was just before last Christmas — and the underlying theme I got was that they’d made all this money off Dark Knight, and Christopher Nolan’s a golden boy, and they’ve got a substantial investment in Watchmen, and they owned their own line of comics, and why did they need this outside thing? They didn’t want the costumes, I don’t think they wanted the black humor, or pretty much anything that’s Marshal Law in it. I said to Pat: if they take all that away, pretty much all you’ve got is a guy with some fucking guns — they can really do that themselves, can’t they?

Over the years, people say they want to do it, they love it — but really what they mean is they want to strip-mine it. For anyone who likes it, the logical stuff is the black humor and the excess. They don’t leave much standing, do they, Hollywood people? They filter and filter and filter. In the end, it’s probably just as well that it fell to pieces. I’m not a big fan, frankly, of the Dark Knight movie and this kind of faux-reality ... it’s an odd thing, when you layer in so much reality. That particular film is like a sub-Michael Mann film or something. The earnestness of it — I found it very boring.

Maybe what people want from a Marshal Law movie is the same situation as “Shok!” and Hardware: they see something in it they want, but they don’t want to get sued.

Almost certainly. It is a minefield, and that’s the problem with all these things.

Did you ever end up seeing any money from Hardware?

Hardware was a very strange experience. Someone who worked for Time Out, when it was being previewed, said, “It looks very much like the story you did in the Annual.” I contacted 2000 AD and asked if they knew anything about it, and Steve MacManus, who I did the story for, said he’d actually seen the film ... and then I started getting phone calls from lawyers saying if I didn’t sign off on this, I’d be sued! And I said, “Well, I haven’t actually done anything. Why is anybody suing me?” It was a bit of a mess. I liked Richard Stanley’s film. As far as I’m aware, he’s never commented on it. They did come to a settlement — I got a small amount of money, I’m sure IPC took the lion’s share, and I never saw the credits on it. They reprinted the comic strip in the DVD, so maybe that means I’m in there.

I think the more pronounced act of larceny was really Robocop — what Robocop did by beating Judge Dredd to the screen was it stole the best of Judge Dredd, and when they made the Dredd movie, they were then worried about being compared with Robocop! So they took out all the black humor and all the satire, and their emasculated movie was almost a Judge Dredd movie, but not quite. Robocop was a more energetic movie. We did hear there were piles of 2000 ADs in the production offices. That does kind of show, doesn’t it?

There was a period between Secret Tribunal and Law in Hell where about four years went by and there wasn’t much in the way of comics by you coming out. What were you doing in the mid-’90s?

I did a couple of film projects, some design work — also Lobo and Batmite. I also did a story for Negative Burn called “The Abyss Also Grasps,” written by Aldyth Beltane, which I really enjoyed. It was only a six-page black-and-white thing, but I remember thinking that was a departure when I was working on that — the drawing style was very free-form and wild and expressionistic. And something a lot of people never saw were strips I did in Penthouse Comix, called Bitchcraft, written by Tony Skinner, who used to work with Pat Mills. At least one or two of those episodes were never published for legal reasons, because they were printed in Canada, and there were all these laws about what kind of imagery and content you can have crossing over the border to America.

You were still having trouble with censors when you were working for Penthouse?

[Laughs.] It’s dogged me like an unfortunate shadow.

What sort of things were they having trouble with?

There might have been an adult female character dressed as a schoolgirl. The Penthouse lawyers thought it could actually be sold in America, but not B.C., printed and shipped from their Canadian printers, without falling foul of Canadian customs. They were decadent sexy occult-themed strips — a lot of fun to do. I also finally got to do a Bizarro World strip for an Adventure Comics Annual which I loved doing. That was written by Tom Peyer.

Me and Alan [Moore] were going to do a Bizarro series many years ago for DC — that’s one of several things we almost did together. We were talking about the Bizarros, and it was all ready to go for Julius Schwartz, when John Byrne was brought in and revamped Superman. So that went right out the window. And before that we were doing the Spectre, and that didn’t happen, and a book for Mike Gold way, way back at the beginning — I should’ve mentioned this — for First Comics, when Mike Gold was first writing about 2000 AD, he approached us — I was going to do the front half of the book, it was going to be two different strips like the old Tales of Suspense or something. Mike McMahon was going to draw the second story, both of them were going to be written by Alan, and it was called Dodgem Logic. But Mike Gold said — we had a letter from him saying as a fan, he’s saying yes, but as an editor with financial responsibilities he sadly had to say no. So that never happened — it was never reactivated, that one.

That title, Dodgem Logic — for a lot of the ’80s it kept turning up in conjunction with Alan’s name in all sorts of different contexts. I believe for a while it was going to be an anthology series for Fantagraphics, as well.

Oh, yeah — Alan has reactivated it as a magazine. It was an interesting project — I think First Comics just weren’t set up to accommodate it. It was a bit outré, a bit on the edge commercially.

What was it going to be?

I had a story where — you were condemned to hell if you’d had your tonsils removed, so it was as arbitrary as that. I just wanted to do a story set in hell. There were extra feature things, there would’ve been a contemporary story, and — it’s like what Alan was doing in Supreme, where you had these 1960s versions of the characters and stuff like that, but way before that. It was interesting, but they couldn’t really see a market for it.

There was another one we were going to do many years ago — Titan Books were thinking of doing a comic anthology, and they had a lot of people connected and circling it: it was Alan, they asked Dave Gibbons, Mike McMahon, Brian Bolland, Frank Miller, those people — and that foundered. Me and Alan were going to do a kind of Fighting American-type strip.

That 50th birthday card that you drew for Alan, “The League of Lost Projects”...

That’s very much on the nose, yes!

Also in the mid-’90s, there was another Marshal Law film project with a company in Britain — I was doing some development work on that, and Pat was writing the screenplay. And then we did the Death Race stuff — I think that was sometime in the late-ish ’90s. And I did a story in one of the Clive Barker books at Epic, written by Dwayne McDuffie. It’s called “Writer’s Lament,” and I thought that was a terrific story — Dwayne did a stunning job. It is rather excessive, but I guess it was the ’90s ...

And it was a Clive Barker comic.

It was Clive Barker’s Hellraiser. Also, there was Blackball Comics, which like Toxic! was one of those startup company things — Dave Elliott put it together with Keith Giffen, and I did a strip in there called John Pain, which was kind of a riff on superheroes and the occult, having a bit of fun. It got caught up in the giant comics slump, and it got buried, which was a pity. In those days, Pat was working a lot for Europe, so we weren’t synchronized to work on Marshal Law stuff. We found it very hard — we couldn’t find a publisher, and thought it was a good time to do other things for a while. I was doing bits of design work, and odds and ends.

It probably wasn’t too long after that when I spoke to Alan Moore, when the League stuff kicked off — that was in the late ’90s. And again, it’s one of those odd things where I’m glad I made this phone call. Where I heard about League was that Paul Hudson, from the London comic shop Comic Showcase, which is now closed but was a fantastic comic store in town — I went in there one day and he said “I hear you’re doing a project with Alan Moore.” And I said “No, no, I’m not...” and he said “Oh, really? I heard something about it on some website or something.”

I ended up speaking to Alan later in the week — we were having a conversation about something else entirely — and at the end of that, as we were signing off, he said, “Oh, by the way, I’ve got this idea you might be interested in,” and he ran down the outline of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. And I thought, Jesus, that is fantastic. It’s just completely different to what I’ve been working on, and it’s got all these major characters in a period I’m very interested in — I’ve got a lot of books, and kind of grew up in a part of South London which is very Sax Rohmer, if you know what I mean. I thought it was terrific, and it gave me a chance to sit down and rethink my style — I knew it’d be a completely different look to what I’d done before.

Your style on the last few Marshal Law projects looked very different from the earlier ones, and some of them look like they were done very quickly — did you want to try something different, or did you feel like it had run its course?

I think it was the money. The exchange rate was terrible for the dollar — we were getting the best we could, but compared to what it was when it started out in 1987, it was getting tough. We felt like we were bashing our head against a brick wall — it was getting tougher and tougher to find an audience, and the whole marketplace was shifting and changing. I needed a major change in what I was doing — I’d drawn an awful lot of people being killed in interesting ways, but it was becoming just a thing you do. I didn’t want to be that guy any more. Some people laughed when I said I was doing a new strip with a central character who was a female, because I’d done all these strips with way too much testosterone!

When I started on League, it was very tough for numerous reasons, but it’s Alan, and his scripts are thick as a phone book. With every series of League, it takes me about 10 pages to get into it. When I did the first few pages, I wasn’t quite sure. Then I found a pace for it, and I realized the fascination of it is not just the exotic nature of the characters and settings but the body language of them. I love the Mina character; she’s one of my favorites. Over the arc of the stories, there’s a lot of subtlety to it, which I certainly wasn’t known for in the past — with my long history of robots and aliens and people slaughtering superheroes!

The other thing is I love the pen-work of the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Charles Dana Gibsons and their English counterparts — it’s fascinating to me. I drew it so it could possibly work in black and white if need be, and then Ben Dimagmaliw, who colors the book, has got the most perfect color palette — we love the atmosphere he layers on it. Bill Oakley sadly passed away after the Black Dossier's first chapter, but from the second series we’ve had Todd Klein involved on design and later Century lettering. It’s the four of us working from series to series. We were wondering what was going to happen after the Invisible Man was killed, after Hyde is gone, Mina has quit — is the audience going to be gone as well? Can we carry this forward? And the new one, 1910, has probably done better than any of the previous ones — it’s got a very kind of robust audience. We have far more women than I’ve ever encountered at signings before — Mina is very, very popular. And the shift in time periods is exciting — we’ve gotten to do the whole 1950s period, I’m working on the 1969 book at the moment. It’s really big shifts, but carrying Allan [Quatermain] and Mina forward from the earlier series — Mina’s very much a constant. And they work: I like them shifting through time like that!

Hyde being as gigantic as he is is not in the Stevenson book — he’s actually smaller than Jekyll, but Hyde being so big was almost a complete accident. The back cover design, with all the hands resting atop each other: Alan wanted a Three Musketeers, end of the first issue of Fantastic Four kind of thing, where you’ve got Ben Grimm’s giant hand with all the other hands resting on it. I drew a hand which was so huge, as a promo piece — that was originally a promo piece, as a teaser — when I came to draw the strip, I thought, Jesus, this guy is huge! He’s just colossal! And this is really the origin of the Hulk, and all those giant characters who transform from a weakling into a monster. And Hyde’s coloring being different-colored skin was an accident — on his first appearance, Ben colored him like he was in the shadows, and that was maintained throughout and we just didn’t say anything about it — it was interesting!

Tell me a bit more about designing the look of Mina — that’s such a striking, gorgeous character design.

Most of the characters were from books I'm familiar with — I’m a big fan of H.G. Wells. Some authors are not too helpful with character descriptions, if you know what I mean. From Bram Stoker, we knew Mina’s age, the color of her hair, color of her eyes, music teacher — there’s not a great deal there. I just thought she should look very fragile. But with a very powerful presence, and she can control these raging characters — she kind of binds them together. Obviously, it’s the sort of thing the movie had no faith in ... [Laughs.]

Well, the movie had no faith in a lot of things.

Yeah, they couldn’t make that one fly, could they? With Mina I found a look for her, which I liked, and over the years I’ve become more comfortable with her. I like the way she does small glances in the more recent stuff when she’s talking with Orlando. Some of my favorite scenes have been with her — when she’s sitting with Mr. Hyde in a tavern having a conversation, I love that scene with the two of them together, and when he crosses the bridge with the tripods and touches her breast — there’ve been some wonderful scenes for her: and her being beaten by the Invisible Man, which was a very strange scene. A lot of people think she was raped — that’s a lot of projection going on. She wasn’t, she was just given a very bad beating ... which didn’t stop Hyde exacting a terrible revenge. She’s a fascinating character to draw. A lot of people love Captain Nemo, they love Mr. Hyde because he’s big and powerful, but I think Mina is probably the single most popular character in the series.

Was there a point when you were drawing the first series that you really connected with it — when you really felt comfortable drawing it?

I think it was the Paris sequence — there was something about that where I thought, “Yeah, this is working.” Likewise, the — well, we can’t call him Fu Manchu, can we? We have to call him the Doctor — those scenes. It was really the atmosphere of the flophouse, and Quatermain stealing the cavorite: I thought we’re really onto something, it’s firing away. And on the second series we kind of came straight hard in on that Martian stuff, which was wild and threw a lot of people, because they weren’t expecting flying carpets and Martians and that kind of thing, but I got to go crazy with Martian fantasies. That was cool.

When was the first time you worked with Alan?

Apart from the abortive projects, I think it was a story called “Brief Lives,” in The Omega Men. And I contributed to a Clause 28 project — an anti-gay bill that was being proposed by the Thatcher government, and I think the idea was “let’s put these people in camps.” It was getting extremely right wing over here, and Alan and his first wife organized a lot of contributors for an anti-Clause 28 project.

So, for these four-page stories, would he give you a phone-book-sized script?

They were always very detailed! Pat Mills was notorious for that as well — some artists wouldn’t work with Pat because he gave them too much detail — but Alan was even more so. It’s always horribly fascinating to me to look at the people who ignore his descriptions, because they end up with this disconnected artwork, like that Woody Allen film where he did new subtitles for a Japanese film. It’s just odd. It very rarely happens with Alan’s stuff. Alan’s scripts are, I’ve said many times before, incredible blueprints, but there’s room to maneuver and design. Alan draws anyway, so he’s very pictorial in his descriptions.

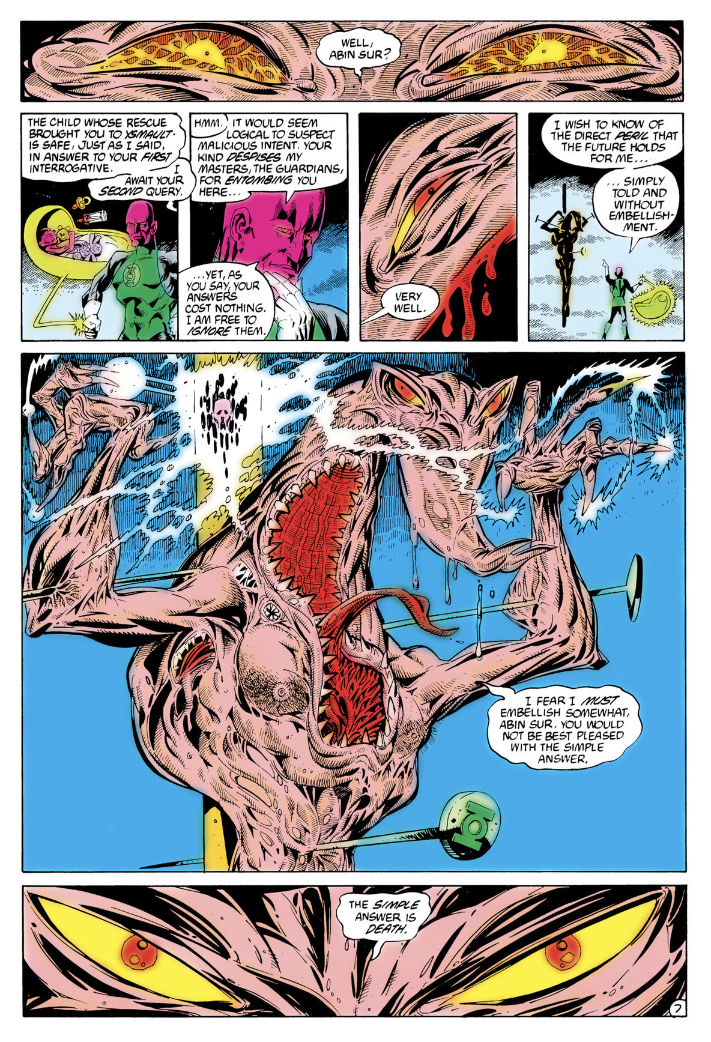

We did the Green Lantern Corps stuff, a few odds and ends — that Green Lantern Corps story “Tygers” that had the Comics Code problems.

Which is to say that Green Lantern Corps story that half the Green Lantern comics being published right now are riffing off of. [O’Neill laughs.] It’s become this major canonical story that everything refers to.

It’s a curious one, that — Alan’s part of DC whether he wants to be or not, isn’t he?

For the benefit of Comics Journal readers at home who haven’t heard the story before, can you tell the story of the Comics Code’s problems with it?

The “Tygers” story was going to be part of the Green Lantern Corps backup series — it was about the temptation of Abin Sur, the Lantern who gave Hal Jordan his ring. It’s a fantastic story, with sinister whispers and half-truths and so on. I drew it, sent it in, and the editor of the book Andy Helfer rang me up and said, “There’s a problem with your Green Lantern Corps artwork.”

I said, “What am I going to have to change, then?”

He said “Well, there’s a problem with the Comics Code — I asked them what could be changed, and they said ‘there’s nothing you can change — the style is unsuitable!’” [Laughs.] He said “we can’t do it without a Code sticker,” and it was briefly spiked.

I rang up Alan and told him, and he was actually jealous! [Laughs.] They published it in an Annual, some time later, without a Code sticker. The Code was on the wane by then. A few years later I went up to the DC offices in New York — I was curious to see an actual copy of the Comics Code. I’d never actually seen one. I’d asked Archie Goodwin, and he said he’d look around, but he couldn’t find it — which is pretty funny, actually! Eventually, he found a very old one, it had some stuff like “no werewolves, no vampires” etc. They did have a phone number on it for the Code, and I rang them up, and this woman answered — I said I was a British comic-book artist visiting New York, and I’d heard so much about the Comics Code, could I come up and visit the offices? And she said, “There’s nothing to see here” — and hung the phone up!

My vision of the Comics Code was always a bunch of old ladies rubber-stamping the back of artwork — I gather it’s probably a skeleton crew, financed pretty much entirely by the Archie Comics people. There’s no British equivalent of that: Taste and sensibilities just shift with society. There was an act of Parliament when American horror comics were coming in in the ‘50s, motivated by a lobby group who saw them as having a pernicious effect on British youth, pretty similar to what was happening in America. There was an embargo on publishing horror material, and no one did for years and years. But back in the early part of my career I did the poster magazine we were talking about, Legend Horror Classics, and someone who bought a copy for their kid complained to their local MP, and the distributor we were doing it for got cold feet and decided to pull the plug on the thing. And that was that. But it wasn’t a censorship thing, it was a distribution thing — and I should’ve mentioned this with Marshal Law, really: One of the early issues of Law, issue 2, the original Epic series, again there was a woman whose son had bought a copy in one of the American bookstore chains, and she thought it was a Superman comic because of the cover — but it’s the rape issue. I got a disgruntled call from Epic saying they’d actually lost distribution to this particular chain. They said it only takes one serious complaint, and they say, "Oh, Christ, this isn’t what we thought we were selling."

How much design work went into League before you started drawing the story itself?

Quite a bit, actually. The original drawings I sent to Alan still had a trace of 2000 AD about them — slogans and stuff on walls, lots of very odd machines and stuff like that. He was very, very polite, but he said, “Drop the slogans and stuff,” and when I looked at it more closely, I could see: Yeah, he’s right. I designed it from the ground up — if there had been anyone else’s version around, it would’ve put me off. The great thing about Nemesis and Marshal Law was it was virgin territory. That was important. I started reading all the original novels and novellas, rooting out details about the characters, like Nemo being Prince Dakkar in The Mysterious Island — all the engravings of him were of this Caucasian, white-bearded, white-haired character, but we ran with the Indian look for him and the Nautilus. The Invisible Man was a lot of fun, funnily enough. I used to lightly pencil him in — his early appearances had balloon tails on his balloons, but I erased that later on, so you don’t quite know where he is.

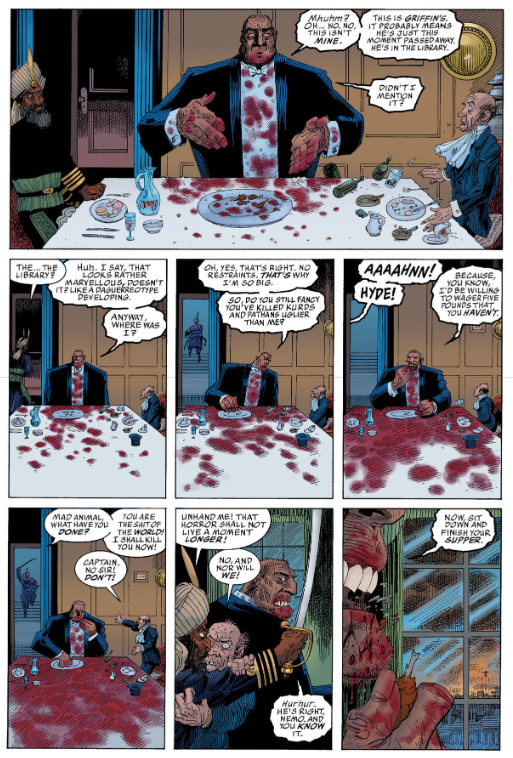

On the second series, when we got to Hyde’s revenge on the Invisible Man, I had a phone call from Scott Dunbier, who was the editor of the book, and he said, “Have you got the latest script?”

I said, “Yeah, it’s terrific, it’s incredible.”

And he said, “Well, could you be really careful?”

I said, “What do you mean?”

He said, “Well, you know.”

And I said: “He’s invisible!” But there’s something very strange about it — it’s the utter politeness of Hyde and what he’s doing. He’s such a monster, and his revenge is so monstrous — I thought that’s a fantastic sequence. And the blood on the tablecloth — that was cool. I think that’s the only area where they were bugged by potential censorship problems.

Oddly enough, in Greece, when they were reprinting that strip, I got a call saying could they extend the shirttail over Hyde’s buttocks? And I said, “No!” They ended up publishing as it was — I don’t think there was any trouble over any issue of League, apart from the advert, the Marvel advert. Which was a genuine Victorian unaltered ad. Which didn’t bother Marvel — nothing seems to bother Marvel!

Tell me about your collaboration with Ben Dimagmaliw. You’ve worked with some colorists before, but you’ve also colored a lot of your own work.

I’ve seen some good coloring, some bad coloring and some stuff that was done very quickly — it almost always bugged me how things looked. It was Scott who suggested Ben, and when I saw it I thought it was absolutely fantastic. I sent him very detailed color notes in the beginning, and the only detailed notes I sent him after that were for the covers — I’d just color a Photostat and send it to him. Now I’ll just color in a dress or the color of a uniform or something he might not recognize. It became more and more notes rather than color notes, because Ben really got it from day one, and contributed a lot to the atmosphere of the book. One thing he does that amazes me is that Ben’s blue skies are informed by someone who’s spent a lot of time in California — our blue skies are never as blue as that! I suppose in our alternate universe, a better Britain, we have a Britain with slightly bluer and nicer skies. And we've had superb letterers on the series, Bill Oakley and Todd Klein. It’s often the case or used to be that people only noticed lettering when they saw bad lettering — misplaced balloons, perverse balloon placement. That’s something I learned working at IPC, I always sent balloon overlays with the artwork, just an old habit. I don’t need to with Todd these days, but it’s one of these muscle memory things.

When you were heading into the second League series, was the feeling different from what it was at the beginning?

Right before the first series came out, Alan told me he’d had a conversation with Alex Ross, who asked him what the new book was he was doing, and Alan told him “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.” I’m probably misquoting him, but Alex said “Oh, it’ll never be successful with a title like that!” I was surprised at how successful the book was — it wasn’t as complex at the very beginning as it’s become now, but when we were working on the early parts of the book, we realized that we were having so much fun dropping in other fictional realities beyond the fictional characters and the villains that this thing could go in all sorts of directions, and it didn’t actually matter if you didn’t get all of it — it’s not there to exclude people.

On the second book, I think we were aware that we had, perhaps, greater latitude with content, and by the Black Dossier, it’d become fairly combustible with DC ... the book was originally for Wildstorm before they were bought out by DC. I might have been working on the first issue when someone rang me up and said, “Wildstorm’s been bought by DC,” and I thought, “Oh, Jesus, that’ll be the end of that, then,” knowing how Alan felt about DC. But Jim Lee and Scott Dunbier flew to Britain and visited Alan personally, and I think Alan felt that so many of the ABC books had artists he’d committed to, Alan naturally felt the honorable thing to do was to continue on those books, but made very, very certain that the books were firewalled — there’s no mention of DC in any of the books, they’re completely separate, the payments come from Wildstorm ... we’ve kept as far as humanly possible from DC. Of course, what happens as the years go by is that Wildstorm, I guess, has become more subsumed by DC. Jim Lee has always been a champion of the book. Jim is doing his stuff at DC, and it’s inevitable that the two companies have merged closer and closer. We did begin to notice that payments at a certain point shifted from Wildstorm’s offices to being paid out from New York, and so on. And also there were these pressures on Alan, like the Cobweb story which was knocked back, and he spent hours and hours on the phone with the legal people, and the Marvel ad, which caused issue 5 of the original series to be pulped ... and that seemed a kind of arbitrary thing. We felt very aware of DC’s presence in things.

After the second series finished — we were very successful, and Scott expressed it in a way that perhaps he may have regretted years later: “You guys can do anything you want.”

Alan was going to take a break then, and he said maybe in a year or so he’d think about doing a third series — I guess he just took pity on me, leaving me as a hobo or something, and he rang me up one day and said, “How about we do a sourcebook?” Just a 48-page thing, with some backstory — a better-quality sourcebook, since most sourcebooks are pretty poor. Inevitably, that led to working out a story connecting up all the information, and it grew from 48 to 64 and then exponentially up — they finally put a cap on it around the 200-page mark, or quite possibly we’d still be working on it now. And when they said, “You guys can have anything you want,” we thought, well, great, we’re doing a story set in 1958, we can have a 3-D section, and there was going to be a record and a Fanny Hill section on different paper, and it was going to be sealed like an old book where you had to cut the pages apart — that idea got dropped later. So we were doing all these things and it was going to be very elaborate, and it was taking ages and ages. The 3-D section — I’ve never read a more complicated script in my life. It makes perfect sense, but it is kind of a headfuck. So we were working on this thing and chaos was created by the problems with DC.

Ultimately, what happened was I was very aware that Alan had all these problems with the V for Vendetta movie — and a collected edition came out with some text wrong on the back cover, all kinds of stuff was going on. Alan is one of the most charming gentlemen you can meet, but you don’t want to cross him. And then there was pressure to get the book out a year or so earlier than it ever appeared, for financial reasons and stuff like that, but it was taking as long as it took — it was just very complicated. Lawyers got involved and looked it over, with dozens and dozens of characters, and it’s set in a more modern period than the previous two books — it was all going fine, it was all approved by the lawyers, it was print-ready, everything was set up, the record was going to be pressed, I designed a label for the record.

And then all the trouble with Scott Dunbier started, where suddenly the book wasn’t right, and — we’re on tricky ground here! A Hollywood film producer insisted on seeing the book, long before publication, in the early part of the year it was finally published. He was putting a lot of pressure on DC, and if I understand the story correctly — I’ll try to keep names out of this — someone important at DC flew out, showed the assembled book to the guy, who was flicking through the pages going, “Oh fuck, oh fuck, oh fuck, you guys are going to be sued out of existence, oh my God, what are you doing, what are you thinking ...” And the guy flew back to New York — we never knew any of this at the time, of course — and things settled down. But suddenly the book was delayed from being relatively quick, like the spring of that year, to being put off to that summer. And I thought oh, Jesus — the royalties from these books really support us, you know? The advance was so small and the exchange rate so poor that the greater the delay the more financially problematic it became.

Then, unfortunately, the same producer was at a book fair in New York, and met someone from DC and said, “Jeez, you’re not still publishing that thing?” It panicked them, and they started taking the book apart. I got a phone call saying — (this was when Scott Dunbier was euphemistically working at home) — because they’re not allowed to ring Alan, you understand, Scott and his assistant Kristy Quinn were the only ones who were allowed to ring Alan — I got a phone call saying, “The book’s got legal problems, we might have to change a bunch of things.” And I said, “Oh, Jesus Christ,” this is like a year after it’s all been approved, people have known the content of this book for literally years, they’ve read the scripts, there’s been lots of artwork finished for a long time. And this is where Jim Lee performed a kind of intervention on the thing, because he wanted the book to come out and he wanted us to be happy with it. So there were minor changes, a few words here and there.

And it was odd, because we’d used Billy Bunter, the Greyfriars character. I pointed out that several years earlier, Time Warner bought IPC — they actually own all that IPC stuff. They own Billy Bunter! So within the company, it’d be easy enough to clear the use of it. But one of the changes made is we couldn’t use his full name, so he’s simply William. Bizarrely, when the book came out, the indicia has a permission thanks for the IPC people for using his full name — which we couldn’t use in the book! When Kristy asked if we could put the name back in, she was told, “No, you can’t touch it.” The whole thing was a legal rat’s nest, and Jim and I were talking almost every day about it for several weeks. He said he wouldn’t send me the complete list of things they wanted altered, because it’d freak me out, which I’m sure it would’ve done. We got it whittled down, and now I had to ring Alan and relay these ghastly fucking changes they want made. There was one final change — to the P.G. Wodehouse-meets-H.P. Lovecraft pastiche in the book, which was very funny. Ever since P.G. Wodehouse was first published, people have been parodying his work and using the names of the characters. But DC decided to dig their heels in on this and say, “We can use the character names in America, but we can’t use them in Britain or Europe, and indeed can’t print the book in Canada for legal reasons,” so it had to be printed in the U.S.A., which also threw things into disarray.

So that’s what happened. That was the final straw. After saying there’s only one thing left to change, some minor color change, equally absurd ... I think Alan felt like you kind of prod someone long enough and they’re going to snap. We thought: This will lose a lot of money for us, but fuck it. The book will come out as we want it to come out, but we guess only in America. And of course, what happened is that bootleg copies appeared via all sorts of sources almost straightaway. At that point, we had decided we’d switch publishers. Because even if we changed things they could always come back with one more petty alteration — it was like having a boot on our neck. As it turned out if not for the intervention of Jim Lee the Black Dossier may never have been published. Which would've been a complete fucking disaster for many reasons.

I believe League is the only one of the America’s Best books that the creators own the rights to. How did that happen?

I think originally when Alan mentioned it to me, it was going to be a stand-alone, creator-owned book, and then it becoming the first of the books under Alan’s imprint happened later. But I think it’s more of a case of the movie rights were sold almost before I’d finished drawing the first issue. Again, I think Jim kept his eye on the contracts on Alan’s behalf — the book was a creator-owned book, and I’m not quite sure why the other ABC books were not. It could be as simple as the artists on them would get a higher advance rate. There’s always a risk doing a creator-owned book — you get very low advance money and take a chance on royalties, which aren’t always there; in fact very often not. I’m not sure; I’ll have to ask Alan that. But we were saying that between us we only own a handful of things after all these years in the business. The shift to Top Shelf and Knockabout was effortless and straightforward. I think Chris Staros thought long and hard about taking this thing on, but after Black Dossier, we wanted to work with grown-ups. Top Shelf had done a fantastic job with Lost Girls, and fielded all the flack and all the aggravation and everything, and it seemed like a natural home. It’s worked out well. We’ve had no dropoff of readers.

I wanted to ask you about the stylistic range that you got to play around with in the text pieces in Volume 2 and in the Black Dossier.

In the first book, we decided we like comic books that are designed cover to cover — Marshal Law, in its comic-book form, was mostly advertisement-free. I used to be on the mailing lists for these things; I’m not any more, but I get so fucking annoyed when you’re reading a comics story and you’ve got some Adidas ad or Lethal Weapon on Home Box Office ad interrupting the flow of a story. It just destroys it for you. So we were responsible for filling the book from cover to cover. In the first one, it was the Victorian advertisements, which I searched high and low and assembled as many as I could — there are only a few fake ones in there. And the letters pages, which Alan did — I sent him a whole bunch of Boys’ Own letters as an example, because they’re poisonous, those old Boys’ Own letters pages. I’m almost sorry we didn’t reprint his letters pages in the books, because Alan’s replies are always very funny and in the spirit of the time.

In the second one, Alan decided on the Almanac — that was a lot of work, more work for Alan than for me, but it was a chance to draw lots of different things. It was fun, and Todd Klein, when he was assembling the final thing, he’s a brilliant designer, so we got the kind of text and picture integration that we wanted. I think some people skip it — we’re aware of that — and some of the sniffy reviews of the Black Dossier ask why it isn’t all comics. It’s an odd kind of snobbishness, really — if you read the text, you do get a lot of hints about the future of the series as well.

Looking at your artwork in that section, there’s the beautiful fake Doré engraving, the medical illustrations, all these styles that you tackle ...

We’re both huge admirers of MAD in its heyday — Bill Elder’s art was stunning. Bill Elder, I worship at his altar. He could really adopt any style — it was just dazzling. I remember looking at it as a kid: You could fall into those pictures and go back and find new things in them, they’re so layered and textured with material. We were trying to get some of that energy, which, looking around, falls into an area where there’s not much in it for people who are actually doing it, you know? You make just as much royalties leaving space for house ads ... but we felt, in the long run, the readers would appreciate it, and we control the look of the book. But the Almanac almost certainly led to the derangement of the Black Dossier, where “you guys can have anything you want,” so — we thought we’d have everything. And ultimately we found we couldn’t have a gatefold, which would’ve been nice for the Nautilus — we had a gatefold in the second collection, which was the game, which was a lot of fun. But they started to pull back from giving us everything. We got the 3-D, which was great, and the glasses. The record’s another thing, where at the last minute — they designed special boxes to ship the Black Dossier in, which were designed to keep the record intact, and at the very, very last minute, they pulled the plug on it. I know people were disappointed.

I was disappointed!

I’ve been talking in interviews for a good couple of years about it. As if we needed any more final straws, that really was it ... it was very frustrating. But I’m very proud of the Black Dossier book. I think some people didn’t know what to make of it when it came out, but it did sell very well. I think it’s grown on people.

I was always curious: what was up with the Golliwog’s appearance in there? How did he come into the picture?

That was a curious one! Going back some years before the Dossier, when we were doing the first series, I saw an article about the Golliwogg books, Florence Upton’s original Golliwogg books, which end with an O double G rather than OG. They were hugely popular, they were published every Christmas — it wasn’t so much a racist icon, a minstrel-suited kind of image. He had a curious relationship with the Dutch dolls, they often walk around naked. They’re very odd books. The text was written by Florence Upton’s mother. I was talking to Alan and I said, “This is very interesting: She never trademarked the Golliwogg, so as soon as the character became popular, people just changed the spelling a bit and ripped her off.” So all the Golliwogs that my sisters had when I was a kid, the whole industry of Golliwogs comes from her just not protecting her rights. We’d been talking about doing the Dr. Moreau stuff, and integrating various Beatrix Potter characters and stuff. When we got around to the Dossier, I’d got a reprint of one of the Golliwogg books, and there’s some strange bit of text in there where he’s described as the King of Panky-Wank. It was very odd language. So Alan devised this whole new language for the Golliwog; and his relationship with the Dutch dolls is ... well, it is what it is. I think the guy’s making out like gangbusters in Toyland.

We had no problems with Wildstorm — no one said anything about it. I did a signing at Golden Apple, and a Black photographer said how much she liked the book, “but I have one problem” — and I knew immediately what she was going to say. I think she called it the Polliwog, I don’t know if that’s an American variation or a slang term, but I told her what I just told you. He’s possibly the only Black figure in that period of children’s publishing — there’s nothing comparable. In Enid Blyton, Golliwogs are evil characters, they’re stealing Noddy’s car and clothes! But the original was quite a swashbuckling character. She was kind of happy to hear that — she didn’t know any of the history, where he had come from, only how he had been subject to grand larceny from publishers and toy manufacturers. We are going to use the Golliwogg again. He’ll come back — we liked him a lot. Some people thought it was going too far.

He turns up on a portrait on the wall in 1910.

Yes, he does. He will appear later. Looking back, when I was a kid I was always a fan of Arthur Rackham’s work ... there’s an incredible amount of suggestion in Rackham’s work, the nymphs and the mermaids and the casual nudity. We accept it when he did it, even in reprint form, but we wouldn’t have had that in contemporary books when I was growing up. They’re very sexy books — I think even to kids they were probably sexy. It’s probably an uncomfortable thing for educators to talk about, but it’s there, running through it. We will use the character again.

You mentioned that the 3-D section was incredibly complicated. What went into drawing that?

The first thing we talked about was we wanted a 3-D section for a ’50s flavor — I think 3-D comics only lasted a year or so, ’54, ’55, that period. We were thinking about how they mostly don’t work — they’re just kind of a crappy “poking spears at you” kind of thing. When I was a kid, I looked at them but I didn’t really read them. Alan thought there must be a way of doing a story in 3-D, so he thought of the Blazing World, and the characters in the story wear the glasses I designed for the readers to look at that section in. And when we got rolling on it, we were talking about all kinds of things we liked — Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo, that sort of thing, and all the characters we could fit in, and fairies flitting in and out of things. But I should’ve guessed what I was getting into when I got the script. It was people walking through layers, and I’d been looking at the old ’50s blinky effects where you look through one eye at one picture and through the other at another picture, so Alan integrated that in, and we used pretty much everything we could. We knew Ray Zone was going to be doing the separations, and he’s the best. I think the most complicated thing I’ve ever done was designing it to accommodate the balloons with the characters walking through the different frames through a party, all the dialogue fitting just right — it was incredibly complicated. And when it’s finished, I think it’s just taken for granted. The big spectacle scenes of airships and things, which possibly to people are more memorable, are far, far easier to do than straightforward people standing at a party in 3-D. That was hellishly complicated. And I think we ran out of room as well — the page count had been set — and the Just So Animals sequence, which really deserved a couple of pages, I think, we had to fit that into a page. But I’m very, very pleased with it — if you read it, it’s actually about something rather than just about 3-D effects. We are going to revisit the Blazing World, so there’ll be another 3-D section in the future. Probably more complicated than this one — who knows?

Did you get a break between Black Dossier and Century, or did you just plunge straight from one project into the next?

We went straight into it. I was working on Century while we were trying to negotiate our way through the white-water rapids and all the aggravation of Black Dossier. Alan had started writing it before I finished the Black Dossier. Alan phoned me — we had a number of alternate stories we could’ve done at this point as a third series — and we were keen on the 1910 period when we have Nemo’s daughter active. The idea of doing three stories over a century, in 1910, 1969 and the present — it’s very complicated, and the other thing we wanted to do was singing. Which again was one of those things where, before it came out, there was this “is this going to work, are people going recoil?” We were talking about how when we were growing up, it was commonplace for people to sing. Pre-karaoke. People sang all the time — it was a pre-television amusement, people sitting around a piano, singing a song, not that unusual. But we thought people might think it was like “Blue Hawaii” or something — people singing a song for no good reason — but the songs were completely integrated. I loved it. And I love the dockside setting and the opportunity to draw these Breughelesque characters in the Cuttlefish Hotel — that was a lot of fun for me. I grew up in South London, and it was very, very Sax Rohmer when I was growing up — rusting old cranes, rusting ships, faded bizarre tattoo parlors. Just fantastic. I wanted to get some of that atmosphere into it.

And, of course, we’ve got Raffles and Carnacki, the new group members running side by side with the occult story that underpins the whole series. It was great going wild with it, and knowing there’s not going to be a boot on our neck about content — we don’t have to worry about that stuff, content, language, visuals — it’s going where it’s going. I think the series is going to be more extreme, it’s going to get wilder. Mina’s the vital component: As everything else shifts around her, she’ll still be there. We love her a lot.

In the future, beyond this series, we’re not quite sure what we’ll do next — there might be a much earlier series set in the ’60s, which is hinted at in the backup story in Century, or we might go into the past with the original League, the Prospero group. As the whim takes us, I think.

You’ve mentioned that there’s a “huge” story that might happen at some point.

Yeah — we were talking about The Wire, the television series, and how that’s clearly constructed to have a story, a completely thought-out arc with a natural ending. It’s not like one of these things like Lost which is clearly made up as it goes along and they retro-fit stuff in. We wanted to have a very clear ending, which wouldn’t actually preclude going back and doing stories from earlier, but there’ll be an ending for the whole Mina arc. Any more than that, I can’t really say, but it’s ... apocalyptic. It’ll probably be the most insane one. It’s fun to think of it in terms of — it’s not going to go on forever, any more than ... I’m sure there’s lots of people out there who’d like to see the Victorian group having adventures all the time, but I don’t think they realize how tired they might become of that, and we’d certainly get tired of it before they were. And it’s being true to the characters. As Alan said, the ending to the second series was the ending of the second series — that group could never have held together any longer than it did. It was built to implode, really.

What keeps a project a pleasure for you to work on if you’ve been working on it for 10 years?

I think it’s the constant shifting and changing. The one I’m doing now, 1969 — when we did Black Dossier, the principal story is 1958. We were both born in ’53, so we have memories of what it was like in Britain in ’58. Our British ’50s was very different to an American ’50s, because we had the undertow of the Second World War, which was still very much present when we were growing up. We were both born into an era of rationing in Britain — Britain was bankrupt, essentially, bankrupted by the Second World War. France had both the misfortune and the good fortune to be completely flattened by bombing, Allied and German — principally Allied, I think — so they were rebuilt, the factories rebuilt, the fantastic railway system built from scratch. What we had was a bombed Britain with a rickety rail system. Everything was falling to bits. Clothes were very badly made. Furniture was shabby. It was a shabby world. It was a lot of fun doing that in the street scenes in the Black Dossier — kids playing football in the street and all that kind of stuff. There’s a guy walking through one of the Dossier scenes, and he’s got a bag thrown over his shoulder, and it’s an old gas-mask case. Which you saw a lot of after the war when we were growing up — gas-mask cases being used as lunch bags and things, work bags. It’s that kind of detail.

And 1969 — here’s our fictional 1969 layered onto what we really recall 1969 being like, which wasn’t terribly Austin Powers. A lot of it still looked like the bloody ’50s. There were pretty poorly cut clothes, even for people who thought they were stylish. It just appeared a little bit sexier. We’re doing all that, we’ve got Soho in the 1960s, which again the whole grubby red light district is interesting — it’s mostly been swept away now, but we both remember what it used to be like, and how tawdry and fascinating and dangerous and gangster-ridden it was.