From the perspective of a skilled storyteller, the appeal of the heist story is that the con artist is telling a story themself. The criminal is affirmed as the hero of the story for how they charm everyone they meet, and each member of the audience delights in being made a mark, following along without knowing where things are going, only brought up to speed at the denouement. The heist movie, with its assembled crew of people with specialized roles to play within the process of misdirecting the authorities, neatly maps onto the collaborative-by-necessity nature of filmmaking. American comics do not have nearly as many heist stories, preferring to tell stories from the perspectives of the criminal’s opposite, the superhero or vigilante motivated to catch crooks. Whether the reason for that is because many American comic book makers are not nearly as good at telling stories as they are just unconsciously reiterating the stories America tells itself I will leave to the courts to decide.

Catwoman is an inheritor to a pulp tradition that goes back, at least, to the French silent film serial Les Vampires. She’s also the inverse of Batman, DC Comics’ most reliable sales performer for many years, the star of several ongoing serials himself at any given moment, and also, for the past thirty-five odd years, the headliner of several perennial best-selling graphic novels with which you are no doubt familiar. Catwoman: Lonely City is a response to Frank Miller’s (with Klaus Janson, Lynn Varley, and John Costanza) The Dark Knight Returns, inasmuch as it postulates a future endpoint for these characters and the ever-evolving mythos of Gotham City. There is a pretty strong argument to be made for The Dark Knight Returns as a right-wing work, but it’s perhaps best described as politically muddled. Lonely City feels far more politically clear-minded, in large part because the criminal’s relationship to authority is far more straightforward than the confused notion of a vigilante who operates outside the law in order to reinforce it could ever be. At the outset of Lonely City, Batman’s dead, but his image persists, alongside his technology, appropriated by the police force, authoritarian in their armor and armed with analytic algorithms that scan the face of every civilian passerby. We are reminded that cape shit and cop shit is basically the same, constituting a singular authority one may be able coexist with, albeit uneasily, depending on one’s ability to avoid them and still do what you want.

How this relates to a cartoonist’s relationship with the superhero publishing industry likely varies by artist mentality. Cliff Chiang’s visual style feels like the ideal argot for a superhero comic to speak in a moment where the superhero concept has achieved full spectrum dominance across major media and its narrative dominates the culture. The iconographic style is akin to that of Steve Lieber’s recent work on Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, one of the few recent DC Comics I’ve enjoyed. This work feels like the closest descendant of another era’s house style — it marries the old José Luis García-López style guide for licensed images, and his approach to dynamic layouts in his sequential art, with an almost Herge-style approach to clear storytelling, here presented in the proportions of a European album, to create something immersively readable. This style is currently an outlier — Jimmy Olsen was viewed as a comedy book, its style considered weird and quirky — among DC books whose look is largely defined by a generational inbreeding among Wildstorm second-stringers and variant covers showing off digitally painted cheesecake imagery, rendering corporate IP as fetish objects offering a pliant gaze to their potential readers. Any stylists more pared-down or classical, evincing an understanding of knowing who Alex Toth or Roy Crane or Jaime Hernandez are, were long ago exiled to cartoon adaptations. Chiang has a velocity to his penline that marks the page too vividly to ever recall someone drawing from a model sheet, but he still draws with enough clarity that we immediately recognize the thing he’s drawing. The visual references woven into the narrative are never ostentatiously signaled by a shift in style. He can draw a composition we recognize from elsewhere, but render it with the same inkline he defaults to. The picking and choosing of visual forebears favors the animated series and its alum. A flashback shows the red night skies of the later seasons that featured more stripped down character designs. Marker lines capture well the shiny texture of the leather costume designed by Darwyn Cooke. Chiang is drawing on a continuity of artistic influence, which is not the same as “DC continuity” in the canonical, specialized wikipedia sense, but is instead the work that is recognized and remembered on account of its quality. It’s a style that feels coherent without being pedantic, and this is partly why it feels suited to this moment. When superhero movies, TV shows, animated features, and licensed products for children and adults are everywhere, and the general public is expected to be fluent in the lore of a property, comics should be able to speak of their own history in an intuitive and visually literate way. Steve Lieber, working with Matt Fraction on Jimmy Olsen, used these references to things the audience recognized to mine a vein of self-aware zaniness, and created a comic that was perfectly fun. The 2006 Doctor Thirteen comic Cliff Chiang drew from a Brian Azzarello script attempted a similar tone. But once you remove the incessant knowingness, you’re left with a deep well of melancholy about the sheer weight of accumulated history, which Catwoman: Lonely City dives into.

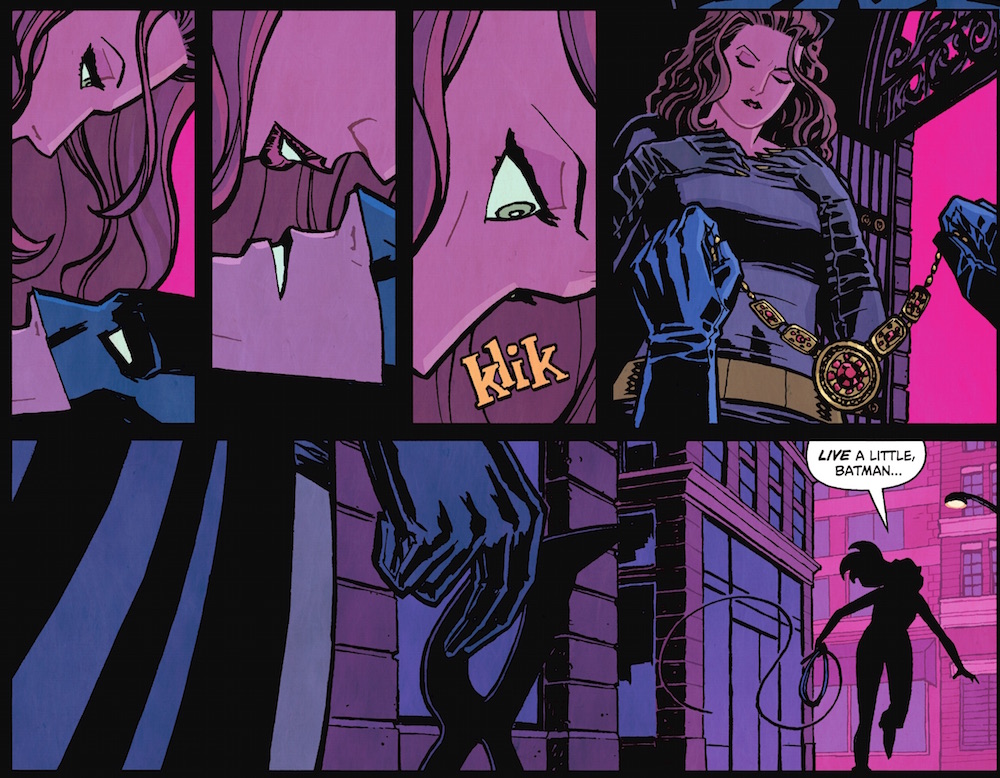

The title does a lot of heavy lifting, setting a mood with the slightest evocation. The feelings and the ideas generated by the reading experience seem to bubble up from the depths, because the reading experience itself is so smooth. This is the first comic Cliff Chiang has done everything himself on — writing, drawing, coloring, lettering — and the visual storytelling is off-the-charts, constantly setting up details in panels that follow into the next, balancing moment to moment storytelling with shifts in visual perspective perfectly. It’s filled with effects that seem like they could only be achieved by an artist in full control of every step of the production process. Part of the reason Chiang seems an ideal stylist for this moment in comics history is how open his style is to color, due to his composition style not relying on shading, which befits where production and printing are at. The first place many people noticed Chiang’s work was the same place many first noticed colorist Dave Stewart outside of his work on Hellboy, 2003’s Beware The Creeper. Handling every step of the production process, Chiang can rely on color to conjure emotion without needing to write too much in the way of melodrama into his script. His choices make understated sequences shine: I was impressed by a scene of two characters walking at night, due to its use of streetlights as both a light source and a page design element.

The inside covers of the single issues include black and white images that allow the reader to see just how much is being fleshed out in color. Generally, my preference is for coloring to not overpower the linework, but it is interesting how much Chiang leaves for himself to do in the coloring stages, how a wisp of a line is used to indicate a shape that will exist purely as color. In the first issue, the image we see in black and white is the first page of the book, which reprises a David Mazzucchelli shot from Batman: Year One, where Bruce Wayne, having returned from completing his training abroad, walks among a lurid street laden with strip clubs, adult bookstores, and cheap motels, his back to us. Here, that’s been exchanged for Selina Kyle, freshly out of jail, entering into a gentrified city. Both have the same edgy posture, of hands in pockets and shoulders raised. While Bruce was surrounded by street-level neon signage, Selina is flanked by the negative space of silhouettes of buildings, walking towards the tall verticals defining the skyline.

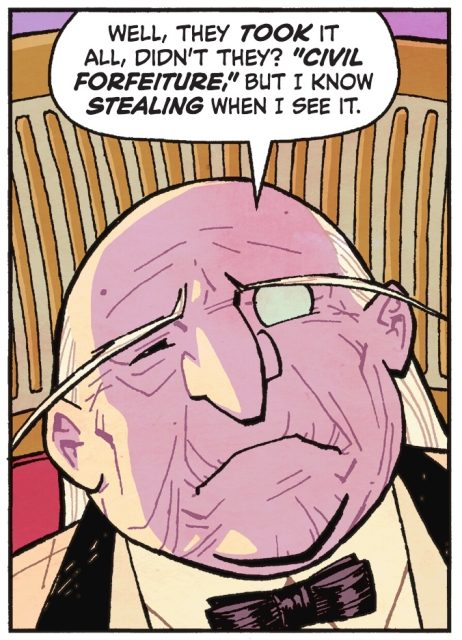

This isn’t the only callback to Batman: Year One. While in that book we got a scene of Batman interrupting a gathering of corrupt officials by saying “you have eaten well,” here we get Two-Face, serving as mayor, saying “we have eaten well” to a group of people seated around a table. While Lonely City is in dialogue with Year One through choices like these, the flashbacks we see are not to moments depicted within that work, but instead to scenes riffing on Julie Newmar’s portrayal of the character on the sixties TV show. Those scenes are great, capturing the character’s flirtatious sexiness and her relationship with Batman by zooming in on the two characters during a pregnant pause, especially because that TV series was considered anathema by DC editorial for decades, partly due to legal reasons and partly to reinforce the self-seriousness of Frank Miller’s take. In both Batman: Year One and The Dark Knight Returns, Selina Kyle is depicted as a prostitute, and this is a take on the character that is never explicitly acknowledged by Chiang. That character choice is, in retrospect, clearly indicative of one dude’s weirdness about female sexuality, and it says a lot about comics that DC editorial just rolled with it, as if unaware of how iconic the character was, how many movies and cartoons would feature her in the intervening decades, all of which would be indebted to Miller yet sidestep that particular characterization.

It is nonetheless pretty interesting subtext, for a story about the gentrification of a major city based on New York and the imposition of a surveillance state, to have the hero be an ex-prostitute, in an era where sex workers routinely get their bank accounts frozen and need to continually find new ways to navigate a digital space that tracks their every move. There’s a pretty strong argument to be made for prostitution being a victimless crime; the counterargument that the prostitutes are the victims being a pretty clear example of moving the goalposts, if used to rationalize a police arrest. Chiang does more than posit the criminal as an anti-hero who the audience roots for, he takes the progressive perspective that redemption is possible and criminal activity may be simply a phase gone through over the course of a long life. The possibility of redemption in superhero stories is largely a pretext, an in-story rationale for why the hero allows the villain to live, when the true overarching reason is to preserve a stable of recognizable properties that can be continually be repositioned against each other anew in perpetual stasis. Most of the endings envisioned for the rogue’s gallery in other “alternate future” stories just kills them off, as that’s the right-wing solution to a presumably recidivist criminal population. By simply letting them move on to other things, we still have the sense that time has passed, and melancholy emerges simply from the pursuit of calmer lives, free of wacky capers.

Here, we are on the side of the outlaw. This allows the book the bypass the trap of so many “prestige” DC projects, where a wholesome nostalgia is venerated to flatter the moral self-conception of the audience, and instead tell an adventure story. The action sequences are predominantly heist sequences, though we get a blowout fight scene at the story's climax. Every location we’re familiar with from decades worth of Batman stories provides an opportunity for a set piece. We know Ace Chemical, with its long narrow bridges overlooking vats of multicolored chemicals. We know the imposing exterior of Arkham Asylum, its name set in the wrought-iron fence, where dangerous criminals are imprisoned. We know the Batcave, with its oversized playing card, giant penny, computer that takes up a whole wall, and that dinosaur. The settings are as familiar as the characters and their homaged panel compositions. The world of Batman is a well-furnished museum, laden with objects and properties recognizable at a glance, inscribed with value. This makes it an ideal location to set a heist. The reader, enlisted as an accomplice, is moved through it all brilliantly by Chiang. It fucking rocks that there’s a scene where they break into Arkham Asylum to steal a skin swab of Clayface’s melting flesh so someone can do a small bit of shape-shifting disguise later on. It’s two scenes I haven’t seen before, that flow perfectly into one another, while remaining rooted in a world I am so familiar with it often can feel I’ve seen every story that could possibly be told within it.

The storytelling Chiang does here towers over anyone else working at DC right now. Compare one of the Lonely City covers to a website’s listing of a month’s worth of DC Comics solicitations, and you will see how no one else creates compositions featuring a meaningful interaction of foreground and background, with an eye towards storytelling. Chiang’s covers depict specific scenes within an issue, and the skillset they show in a single image, capturing fully-realized settings with conflict and danger, is in evidence within the reading of those sequences. This skill I’m describing probably sounds like the bare minimum of what a comic book cover should do: make a promise of a story and a visual tone and then fulfill it with aplomb — and yet it doesn’t seem anyone else is trying to achieve these goals. I don’t want to couch my praise for Lonely City in shitting on DC’s other books, but you can’t take in a five-course meal like Chiang has provided without using the toilet. It is extremely rare for a contemporary superhero comic to be this eminently readable, but Chiang employs this high level of storytelling technique to go even further, making sure the story he’s telling actively does something. It whips.

The post Catwoman: Lonely City appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment