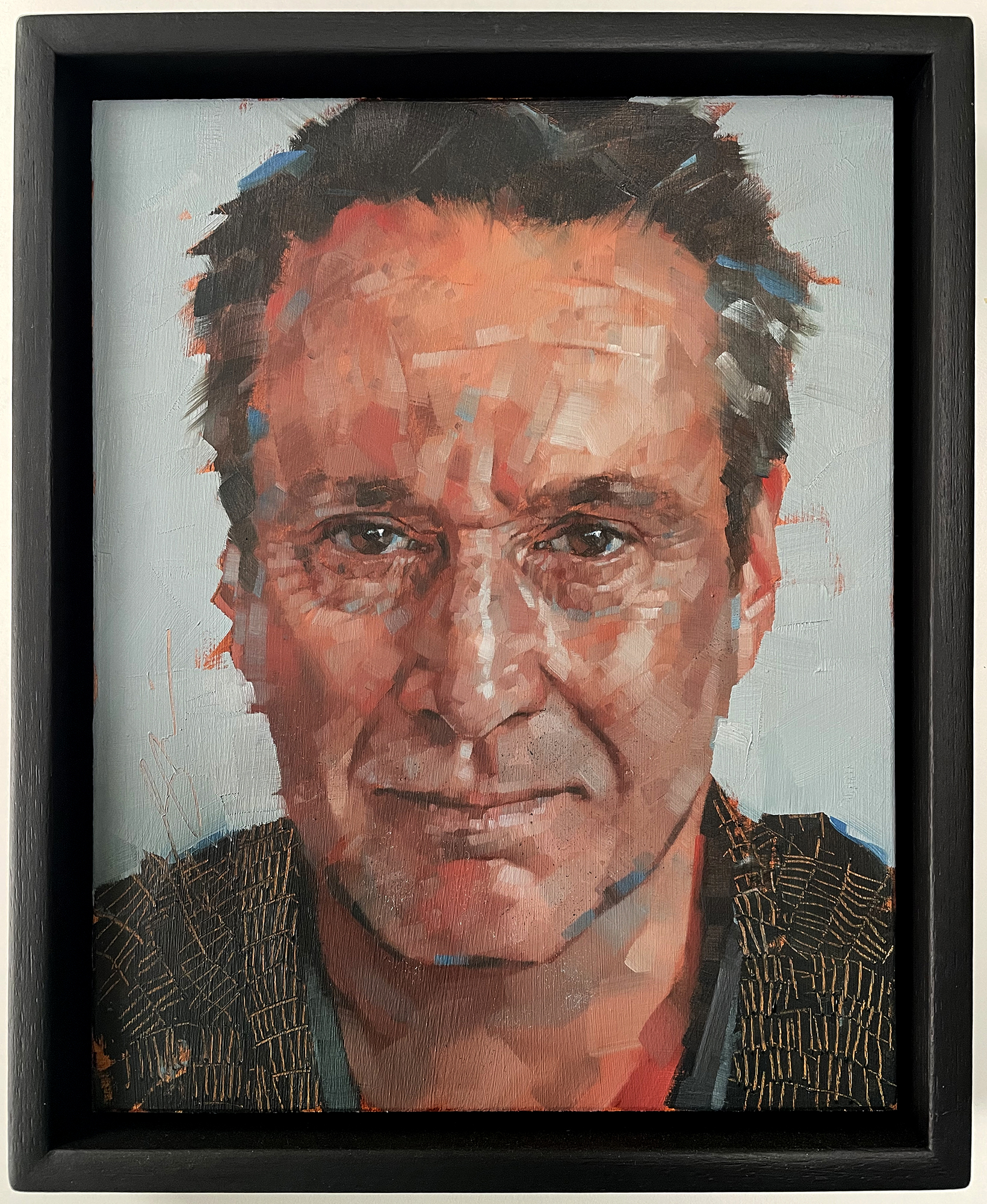

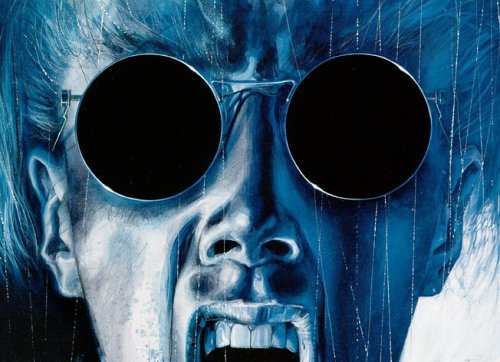

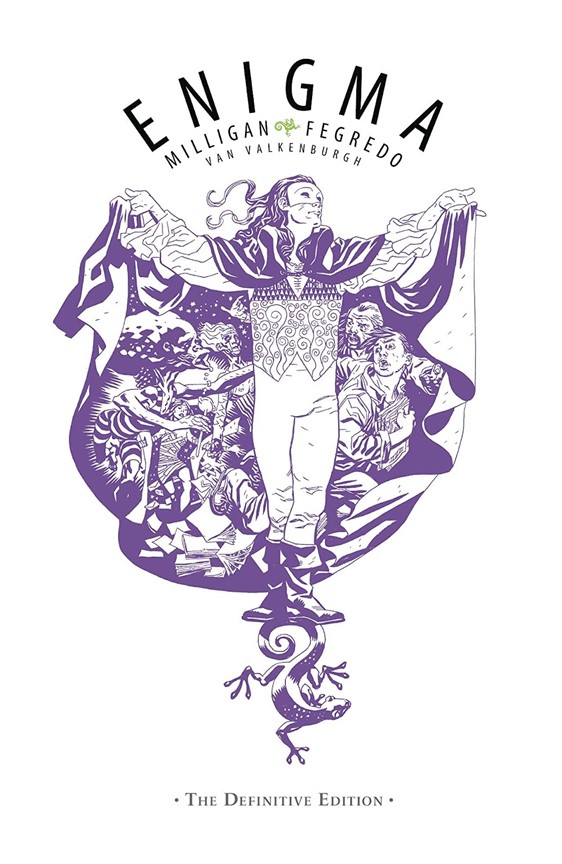

Duncan Fegredo’s career ranges from being one of the defining Vertigo artists, to the infamous British magazine Crisis, to the killer of Hellboy. His collaborations with Peter Milligan are legendary. From Enigma, to Girl, to Face to, one of the all-time great Spider-Man stories, “Flowers for Rhino”, the two crafted beautifully told stories with unique voices, each of which had its own style and approach. Enigma in particular remains a brilliant work three decades after it was published: a look at sexuality and repression, superheroes and fantasy, with a "Definitive Edition" published by Berger Books, an imprint of Dark Horse, last year.

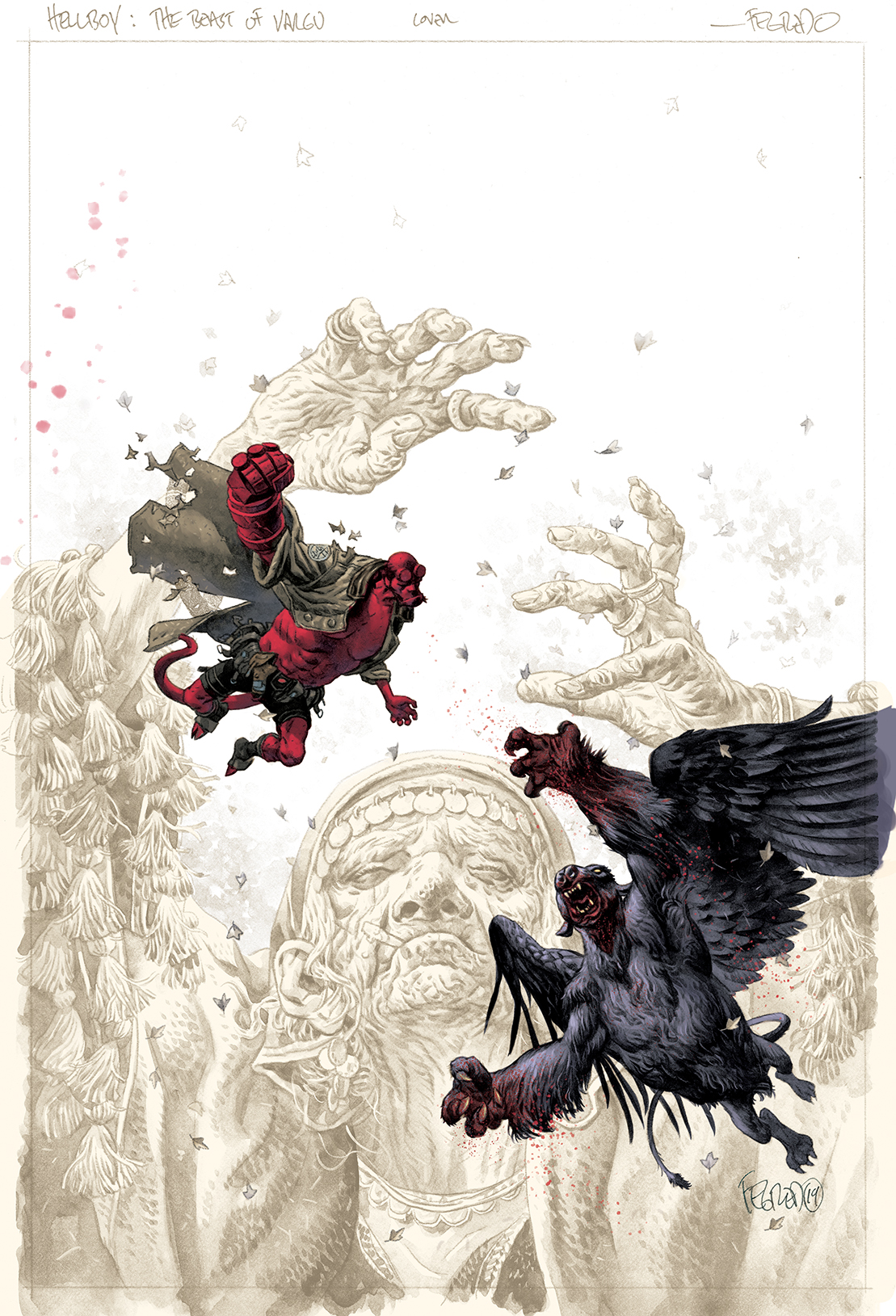

His other great collaboration is with Mike Mignola, for whom Fegredo drew multiple Hellboy miniseries: Darkness Calls, The Wild Hunt, and The Storm and The Fury. These served the epic conclusion of Hellboy’s saga, ending with the character's death. Drawn years ago when relatively few other artists had drawn Hellboy, Fegredo managed to put his own mark on the character. Since then, Mignola, Fegredo and Dave Stewart have collaborated on the short graphic novel The Midnight Circus, which marked a stylistic shift for Fegredo and featured some of his finest work.

Fegredo got his start working with Dave Thorpe on Heartbreak Hotel, drew comics for Crisis and 2000 AD, and went on to draw the Vertigo Kid Eternity miniseries written by Grant Morrison and Millennium Fever written by Nick Abadzis. For the then-upstart publisher Oni Press, Fegredo chronicled the escapades of New Jersey’s two greatest stoners, Jay & Silent Bob, written by Kevin Smith. Over the years he’s been a prolific cover artist, working on everything from Star Wars to Shade, the Changing Man and Aliens . He’s contributed to anthologies including Weird War Tales, Flinch, Dark Horse Presents and drawn issues of Tom Strong, House of Secrets and X-Force. More recently he illustrated and co-created MPH with Mark Millar.

Fegredo and I exchanged e-mails to talk about his work and career, a disastrous project at Marvel, and why he loves detailed artwork but finds his finished work dissatisfying.

ALEX DUEBEN: What comics were you reading as a kid? What things in general obsessed you and made you go, I want to be an artist?

DUNCAN FEGREDO: As I kid I read any comics I could get my hands on. For the most part that meant British humor comics, simply because that was what was available. I suspect they were mostly passed on to us, we didn’t have a lot of money to spend on such things. Stuff like The Beano, The Dandy, Beezer, some boys adventure stuff like The Hotspur. The little pocket money I had went on Whizzer and Chips. Later there was a Disney comic, that was probably when I started copying the drawings, when I first made a connection to how these things were made, not that I thought of it that way at the time. This is the very early '70s, I was born in 1964. My elder brother had a friend who lent us Power Comics, they reprinted Marvel Comics before Marvel had an official foothold in the UK with The Mighty World of Marvel in 1972. I was hooked pretty early, I’d buy a lot of the British reprint books. The real hook came with Star Wars, I was obsessed. I think at that point I drifted away from US reprints, I wanted science fiction and 2000 AD fit the bill perfectly. So first I wanted to work for Disney, then Marvel, then 2000 AD. I mean, I wanted to be a spaceman first but asthma made that unlikely. Little did I realize that being a sickly loner child set me up better for obsessing over drawing and comics.

What’s your background? Did you study art?

I always drew. I realized it was something I could do better than the other kids, even when very young. I wasn’t the most gregarious child, I found it more comfortable to be on my own, drawing, so I just improved by the simple fact of solitude. Later, when it came to study, my mum would say, that’s great, but concentrate on the more academic subjects. Which I did, rather half-heartedly.

Eventually I did what I always wanted, took a degree in graphic design at Leeds Polytechnic, with the intention of specializing in illustration. On paper the prospectus looked great, it suggested the course would touch on animation, science fiction illustration, film, etc. Which I suppose is true if you had the focus to do it all yourself. The reality was rather different. This was 1984, computers were not unknown, except at Leeds Poly where countless hours were wasted making us visualize typography by hand. It was a dead skill, which pretty much summed up much of the course. The one good thing about attending Leeds was meeting my now-wife, Diana. I couldn’t have gotten through the intervening years without her support.

I coasted along for a year and finally reconnected with comics in my second year. The only comic I continued to read at that point was 2000 AD. I chanced across a copy of Daredevil on a news rack, picked it up, flipped through, put it back. I returned the next day and repeated the process. It was the "Pariah" issue of the Born Again story line [Daredevil #229, April 1986], and it bothered me. Mostly I really disliked the cover, but I couldn’t stop looking at it. I purchased it, read it repeatedly, pored over those almost crude yet so naturalistic drawings. A new comic shop had also opened in Leeds, something I’d never really had access too. Most of that second year was a bit aimless, just the loosest desire to draw comics. I also spent a lot of time going out sketching in shopping centers, on the street, trying to improve my figure drawing. I don’t think I did any life drawing at all in my three years at the Poly but these self-motivated drawing sessions gave me a real grounding that has informed everything I’ve done since. I mean, they were horrible drawings but the act of observing and trying to make a record of folk sitting, drinking, doing life stuff really stuck. My tutors weren’t much impressed by my apparent lack of progress so a few projects were suggested for my final year, I chose to illustrate John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Was this around the time you met Dave Thorpe?

During the summer of ’86 I return home and commenced deciphering the Milton tome. It was uphill work, but rich with imagery. Satan's fall from heaven, demonic councils in hell, a cast worthy of any overwrought comic. I scribbled away and hit up the idea of drawing them all as biomechanic creatures. Or something, I don’t know why. I was still overly fond of H.R. Giger and that kind of got entangled with my liking of Ralph Steadman. I was also reading more comics, a friend lent me his run of Warrior comics and turned me on to Watchmen. In my mind Paradise Lost and comics were becoming entangled. Just before my final year at Leeds commenced I travel down to London with that friend to attend the UK Comic Art Convention; it was and remains the best convention I ever attended. It blew my mind. Real artists who drew real comics, everywhere. And accessible. Up until this point I knew artists drew comics, but the how and why it could be possible was unknown. But here were real artists I could talk to and watch as they sketched for fans. It was just wonderful.

I had prepared for the convention by putting a small portfolio together. Mostly work in progress stats of my Paradise Lost work, fiery robots in hell. I may have had the only four pages of comics I had drawn at that point as well, large-scale pages drawn in a sub-Gilbert Shelton underground style. I’d drawn them the previous years, the result of a piece drawn for Martin Salisbury, a first-year tutor and the only one to share any interest in or encouragement for comics. But I’d already moved on from there, so probably not. So I showed the art to any artist willing to look, if the moment felt right, but mostly I observed. I recall meeting Brendan McCarthy in his wonderful exhibition of Artoons, he took a look at my folio and said I could ink him anytime. He was being kind of course, but his work in 2000 AD was a big influence on me. His figure work in the opening chapter alone of Sooner or Later–written by Peter Milligan–along with Ian Gibson’s work on Halo Jones really impressed on me the importance of body language.

Late on the last day I was perusing the publisher tables. I didn’t really know anything about Escape, but publisher–and nowadays historian–Paul Gravett was on the stand and was happy to take samples of my work. Some time after I had returned to Leeds I received a very enthusiastic letter from Dave Thorpe. Dave’s Doc Chaos comic was published by Escape, Paul had passed along my samples and piqued Dave’s interest, and so we corresponded during the year I finished my degree. The plan was for Dave to reboot Doc Chaos with me on the art. It was slow going. I never really got the strip, I wasn’t remotely on the same wavelength. That and I still hadn’t really drawn any pages. I don’t think I got more than 15 or so pages drawn, they were terrible.

So your entrance into comics is yet another story of Paul Gravett connecting people and projects?

I wasn’t really aware of that at the time. I’m not sure I was even aware of Escape magazine at the time, but then for a college student I was woefully unaware of more mainstream-style magazines as well. It was only a year or so later that style bibles like The Face and i-D Magazine would start to feature comic articles about Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. There’s no doubt that Paul’s interest in my work started a domino effect.

Your first published work was a strip that Thorpe wrote, "Repossession Blues", in Heartbreak Hotel, is that right?

My first published comic, yes, but not my first published work. I had drew a series of illustrations for Interzone magazine. When the Watchmen signing tour passed through Leeds, I went along with my folio and got talking to organizer Mike Lake - along with Nick Landau, who was one of the founders of Forbidden Planet and Titan Books. He thought my Paradise Lost stuff would be good for Dragon’s Dream. Of course I utterly failed to follow up on this as I just thought he was being nice. There is a theme here, isn’t there? Anyway, one of the editors of Interzone was watching all this and introduced himself, he was in need of artists for the magazine and by an a remarkable coincidence lived about a five-minute walk from me.

"Repossession Blues" was the only comics work I completed with Dave. I never even got paid for it, but it served me well as a calling card. It was raw and muddled, not all my fault, but the sheer scale of a tabloid sized comic had impact.

You also did some illustrations for Thorpe's Doc Chaos, is that right?

The comic pages were never completed, never saw the light of day, but they were highly referenced by the artist who drew the book that finally saw print. Other than that I made one illustration for Dave’s Doc Chaos novella, The Chernobyl Effect. (I recall sitting next to Brett Ewins [at a signing for the book], though my absence in these pictures suggests a bathroom break!)

How did you end up filling in for Jim Baikie and drawing New Statesmen in Crisis?

The way I remember it, I received two phone calls in September of 1988, around two weeks apart. The first was from Karen Berger offering my a three-book prestige series called Kid Eternity. I don’t recall any other details, but I accepted - and obviously went into a blind panic because I still had no idea of how to make a comic. It was worse than that, in my mind "prestige book" meant it had to be painted like the Black Orchid series Dave McKean was making for DC. I’d spent the preceding years drawing scratchy, splatter black and white art, the idea of full-color painted art was just beyond me, but that’s what was happening because of a new and cheaper printing process. I was, and still am, red-green colorblind. Not to devastating effect, but enough to cause problems. It had always been a stumbling block.

Two weeks later I heard from Fleetway editor Steve MacManus regarding a couple of fill-in episodes of New Statesmen. Again, I said yes, I’d worry about the details later.

Now that I think about it I also heard from Steve Dillon, who was co-editor of Deadline magazine - would I like to illustrate some prose by Pete Milligan? Why yes, yes I would. Well, that never happened. Which is a shame as I would have been better suited to that over the comics work.

The reason all these offers came around the same time was because both "Repossession Blues" and samples of my Paradise Lost illustrations had been circulating in the Society of Strip Illustration, later known as the Comics Creators Guild. The work sparked interest in various quarters. Not that I knew at the time, I only ever attended one meeting, years later. My work got seen, connections made.

I figured I would do the New Statesmen work first, learn on the fly, and then apply that to the larger project that was Kid Eternity. Fortunately Karen was okay with this.

A few weeks later I had a meeting with Karen Berger at the Russell Hotel, just around the corner from the UK Comic Art Convention, or UKCAC as it was known. It was exciting but complicated by the fact I was staying with Dave Thorpe that weekend. He wasn’t particularly happy that I had all these offers of work and none of them included him in the picture. But he had a day job, working at Titan Books. He showed me a letter he’d sent to Karen trying to sell us as a team, I was less than happy about that as it was done without my knowledge. During a meal we both attended at the end of the con it became apparent that Dave, along the table from me, was sat next to Vortex Comics publisher/editor Bill Marks, selling him on the idea of publishing Doc Chaos. Without any previous discussion and knowing full well my interests lay elsewhere.

Of course I still had to learn to draw/paint and assemble a coherent page of comic art. Sigh.

Crisis was an interesting magazine with a lot of talented people. It only lasted a few years but what was it like? Did it feel like something exciting and different and new?

I was actually hoping to work for 2000 AD, I’d even sent pages of Paradise Lost and a couple of single page Judge Dredd strips to editor Steve MacManus. He was positive but regarding the Dredds he advised me to "lose them, not good.” I reacted poorly at the time, though of course he was right.

I didn’t really know what to make of Crisis at the time. It was rather more self-aware than I was, I’m afraid I was aware of the troubled world around me in the most passive way. I could see that Crisis could fill an editorial need, entertain but provide a viewpoint, food for thought. If only it hadn’t been so earnest. Deadline emerged around the same time, some people saw rivalry there, stupid really. It was definitely more hip, much more fun. I suspect if I’d worked there first, things would have developed very differently. I can’t imagine I would have tried to develop my work the same way.

You drew two New Statesman stories and then you also drew two Third World War stories, do I have that right?

Yes. On New Statesmen I attempted to work in a way that would fit in with Jim Baikie's style, line and wash. To say I struggled would be an understatement. In the second episode I tried to inject a little more spontaneity, an effort to cover up the obvious: I had no idea what I was doing. I changed my approach again when it came to Third World War, partly because I’d seen Simon Bisley’s Sláine pages at the Crisis launch party, they were just amazing to behold.

For Third World War you worked with Pat Mills. Did you have much interaction with him?

I’d spoken to Pat a few times before Crisis, only you don’t really talk to Pat, you listen. A lot. I don’t mean that as a criticism. He just had a lot of ideas and I think he called people to use them as sound boards, to siphon off his busy mind. His scripts were very precise, they would contain notes to reference the various cuttings from National Geographic he included. Very helpful.

You were also drawing covers for Crisis, a Third World War reprint, Judge Dredd Megazine in this period as well. Cover artwork is something you've done a lot over the years. How did you start?

They needed covers and they asked me, it was that simple. I had gained a degree more proficiency by that stage, simply by drawing and painting those four episodes in Crisis. The first Judge Dredd Megazine cover was art directed by Sean Phillips, he proved a marker pen sketch layout for me to work from.

And so you were doing all this while also working on Kid Eternity?

No, this was all, or mostly all before even starting Kid Eternity. I’m still amazed that Karen and DC were willing to wait for me all that time, but it was in their interest as there was no chance that I would’ve been able to draw Kid Eternity without that experience. It would have been a very different book.

Did you and Grant Morrison have much interaction while working on Kid Eternity? Did you know each other before?

Not really. We met a couple of times, but that was it. At the Crisis launch party I recall them telling an eye-opening tale of their experimentation with chaos magic. It involved a lot of masturbation and “Then the sun came out!” I think I called them once to ask about something in the first script but it was a bad line, I could barely make out their voice.

So when exactly did you start Kid Eternity? Did you feel ready?

It must have been somewhere around the end of 1988 or early ‘89. I know the whole thing took me a couple of years to paint and I recall reviewing the lettering placements in my hotel during San Diego Comic-Con in ‘91. I was there to promote Enigma and Touchmark [an abortive 'mature' comics imprint for Disney, for which Enigma was initially conceived]. I was surprised I was up for an Inkpot for my work on Kid Eternity. We all went to the pub instead. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I’m not sure I would ever have felt I was ready, at that stage I was in a continuous state of trying to find a way to work that fit, that felt right to me. I was very susceptible to outside influences and during Kid Eternity that meant the work of Dave McKean. I was already very taken with Dave’s illustrative approach on Violent Cases, that only increased with Black Orchid and Arkham Asylum. I could see Dave was using a lot of photo ref and that made sense to me so I purchased a camcorder with the intention of filming myself and freeze framing to provide figure ref. It didn’t really work, the pause was far too jittery. I never did get the hang of using photo ref, I always found it made my work horribly stiff and unconvincing. Instead I purchased a tall mirror and would act stuff out to myself, hold it in mind and freehand it. So I was trying to paint in acrylics, concerned about color blindness, trying to photo ref but fudging it in my head and still trying to get to grips with following a script with a degree of clarity.

Were you getting one script at a time? What was the process like then?

I think I did loose layouts for the first half of book one; Karen Berger gave me notes and highlighted any problem areas. I’m sure there were a great many, but she was very patient. Rather less so by the time I’d gotten to the end of that first book, and who could blame her? Alisa Kwitney was my editor for book two followed by Art Young on the third. I was just that exhausting.

As far as the art, the painted pages, the colors - it's a stunning book. What kinds of works and people were you looking to and thinking about in trying to find the right approach?

The major influence from the start was Dave McKean’s work on Black Orchid. I was contracted to produce art for a book in DC’s prestige format, the same as Black Orchid. In my my mind it was clear that was how it should be done, it was an easy direct comparison. Even the tone of the script fit, though Kid Eternity had more moments of dark humor. I’d only read a little of the original Kid Eternity but it was clear to me that anything I could do to make the book feel a little more grounded in reality would help sell the story; the painted approach seemed to me to be a good fit. The fact I was still learning to paint was just an added bonus to the journey, I wasn’t going to let that get in my way! I didn’t know enough to realize how much I had to learn. Dave’s Arkham Asylum left its mark on my work, as did George Pratt’s Enemy Ace[: War Idyll]. You can see evidence of that in the third volume. I was also looking at Bill Sienkiewicz and Kent Williams throughout. Most of these influences are about technique, the storytelling I was learning from everywhere.

This was pre-Vertigo, but by this point Karen Berger had edited and overseen a number of books. Was she making clear, or were you thinking: Kid Eternity has to be a book that looks and feels like these other comics?

I don’t recall Karen impressing her style preferences at all, other than asking me to tone down a couple of panels where I had overstepped the boundaries of taste. I trapped myself into thinking the book had to be done a certain way, something I do to this day. Maybe I should say I simply have a vivid response to the script!

I will say, whatever else can be said about the book, you drew a great vision of hell.

There you go, that’ll be my response to the script! Grant wrote vivid descriptions of hell and everything else, they are, after all, an artist as well. In fact the first script and series synopsis was accompanied by a few sketches of how [Grant] envisioned the Kid; I only changed the hair.

Was it Art Young who put you and Peter Milligan together on Enigma?

As I was finishing the last volume of Kid Eternity, Art Young informed me he was leaving DC. I don’t recall if he specifically mentioned Touchmark at that point, he just said he had two series he was considering me for, both written by Peter Milligan and both titles beginning with the letter “E.” I’m pretty sure that was all the information I had to go on, but being as I was long time fan of Peter’s and his frequent collaboration with Brendan McCarthy I readily agreed.

Whilst Peter and Art attended a convention in, I think, Italy, Art wrote me describing a few thoughts on what the character Enigma might wear, his general appearance. A cloak, the opera mask, it was pretty much all there. I added all the Klimt patterns, I was into Gustav Klimt at the time and it just fit with Art’s theatrical suggestion.

We needed a few images to launch the Touchmark line at San Diego, I really only had the character design to go on at that point so made a simple character poster and a few abstract panels to adorn a leaflet. I hadn’t read a script at that point.

So when you finally got a script for Enigma, do you remember your reaction? Do you like to know and understand the story before you draw it or are you happy to work with what’s in front of you?

Ideally you want to know the broad strokes of the story before you start, if only to give a sense of how you pitch your art at the onset compared to where you want to end up. It’s easy to say that in retrospect, but at the time I don’t recall it was a conversation we even had. I’m probably wrong, Peter more than likely gave me a pithy overview in three sentences. I just don’t remember. I’m sure Art Young knew more. I’m pretty sure I put my faith in Peter based on his previous work, I was already sold. What I do recall very clearly is how Pete and Art presented me with the final script at a convention in Glasgow. The only place I could find to read it was a bathroom stall; why I didn’t return to my hotel room is not so clear. The stall was nearer I guess, and I’d had a couple of drinks. I clearly had no idea of how the story was going to play out because that script just blew my mind, it was as if a key had turned in my mind and all the tumblers fell into alignment, it was amazing. All those hints in the story that I’d just taken at face value… it’s like now we’re used to that sort of thing in longform TV shows, but how often do those tantalizing mysteries ever pay off? So often you reach the end and those moments go unmentioned, no explanation.

Was the original plan for Enigma to be drawn as opposed to painted? Was that something proposed to you, or did you suggest that?

I don’t think it ever came up, I assumed from the start that it was going to be a regular book so that meant line art. It’s not something that ever occurred to me and now I’m imagining what could have been.

What was it like working with Sherilyn Van Valkenburgh, who handled the colors? I would imagine after painting a book, it’s easier in a sense, but do you keep thinking of color as you’re drawing?

I met Sheri at a London con (UKCAC), she must have been several issues in at that point. I don’t remember much of what we talked about other than me enthusing over her work. I didn’t offer any suggestions as to how she might approach coloring my stuff, I assumed she knew what she was doing. She’d done a great job coloring Mignola on Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, so I was in safe hands. It was still a bit of a shock to see the first pages of Enigma colored, it took a few beats to realize the problem wasn’t Sheri’s color, it was my work - I wasn’t Mike Mignola! Once I got over that I realized I needed to rethink the way I was drawing, hence the gradual change to more open artwork, more clarity. Clarity for me, at least.

How much freedom did you have as far as the script, the page layouts and design? Because rereading the book for the first time in a while, it has this incredible energy.

Thanks, that is really great to hear. I just responded to the script in any way that I felt best served the story, I don’t recall any push back from Art or Peter, even when I did anything that wasn’t asked for. There was nothing in the script about the Truth growing in size but I felt it fit the themes and dramatically it had more impact. I’d add or take away panels as I saw fit, not changing the dialogue obviously. But if an extra beat worked I’d draw it. Nothing major, really, but I got used to doing that over the years.

Several decades later that would drive Mike Mignola crazy!

In the introduction to the new edition, Peter Milligan mentions that your art changed over the course of the run and he said publicly that it was deliberate and explained why in a story context. But were you conscious of this change as you were drawing the book?

We both address this in the new edition, Pete in his foreword and I in my afterword, "Secret Origins or a Brief History of Style". Pete maintains I believed his conceit of my changing style reflecting Michael Smith’s journey but that really is not the case. Pete came up with the idea during an interview and the interviewee accepted it as truth. I was just flabbergasted, it was such a brilliant off the cuff confabulation to explain my changing style that I went along with it for the benefit of the interview. I did repeat the story afterwards but simply because it was a lot more elegant than admitting I despaired of my drawing and was desperately trying to improve, though anybody that knows me will recognize that admitting the latter is never far from my mind. It was a very conscious effort to bring some much-needed order to my chaotic lines.

As far as the book being set up at Touchmark and then published by Vertigo, what was all that like from your perspective? How did all that play out?

I wasn’t aware of the problems at Touchmark, I don’t think Art wanted me to be distracted from drawing. The first I heard of it came from Paul Johnson who was painting Mercy for Touchmark. I think by that stage Art had been in negotiations with both Disney and DC and the deal was all but done. There may have been a relatively brief period of uncertainty for me but on the whole I simply went from being paid by Disney to being paid by Warner Bros. Disney’s lack of faith was Vertigo’s gain, they got to launch with some very strong and individual books.

My wife Diana remembers it as rather more stressful, including a dip in my health. She’s probably right, I was just focused in on the book and my ongoing struggles to improve.

What was the reception to Enigma like, because it seemed to sell well and it’s never been the most popular comic, but it is beloved and I know that it’s meant a lot to a lot of people.

It sold well enough to make decent royalties, even by the final issue. Where it found its audience it was very well-regarded, as it should be, for Peter’s work at least. I’m sure my work was a hard sell to many, at least the early issues. I’m sure many missed the changes for the better. By the same note I’m guessing a fair lot found the writing a little too aloof and missed out on the latter revelations. Their loss. The reviews I recall were positive, the book gained us awards in the UK but the Eisners didn’t know the book existed. It was years ahead of its time and it wasn’t The Sandman. Hopefully with the release of The Definitive Edition it’ll gain the attention it deserves but it seems the Eisners are still unaware of its existence.

You drew a couple short comics for Vertigo around this time, a Kid Eternity short with Ann Nocenti, and a King Mob one with Grant Morrison. Do you remember anything about them or how those came about?

It’s funny because I never thought of it as working with Ann Nocenti; as far as I was concerned I was I was working with Sean Phillips. Sean was the regular artist of the Kid Eternity monthly. He asked if I fancied collaborating on the short story and it sounded fun because I’d never been inked, or pencilled for anybody else before. I pencilled the first half, Sean the second, then we inked each other's pages. It felt odd working over Sean’s pencils, similarly seeing his inks over my lines; it made me question what I’d drawn to some degree, how my lines were perceived. I’m sure I should have learned from the experience, but really, what was I was expecting to learn from eight pages?

I don’t remember much about The Invisibles story, other than I lost steam after the first couple of pages. It was hard to find any flow to it and it showed in my clunky layouts. The problem with a short story is that you don’t have much time or space to get to grips with the characters, it’s all over before it begins.

After Enigma, were you and Milligan interested and excited to do something else? Was Vertigo interested in keeping the team together?

I was happy to keep working with Peter and Art, I think we were all keen to build on Enigma, it just made sense.

Was Face an idea that Milligan had that he pitched you? Was the idea of making a one-shot comic more appealing than a long project at that point?

Pete was always generating intriguing ideas, Face was one that was directed at me, possibly via Art Young or at a convention. We weren’t in regular contact. We’d say hi at conventions or if I was down for a meeting at the Vertigo office in Wardour Street, London. I’ve rarely been in close contact with a writer, I’m fine with getting on with the script, doing my thing. There’s likely a discussion up front and maybe the odd query that I need clarifying, but otherwise I just do what I can to make the best of the script.

I think Face may be the best single script I’ve drawn. That or Hellboy: The Midnight Circus. Both are perfect one-shot books, though Midnight is best enjoyed with knowledge of earlier Hellboy stories. I thought Face was just perfect, less than 60 pages yet it doesn’t feel compressed. What it is, is thoughtful, darkly comedic and incredibly shocking. Long runs are great to read but generally I have neither the speed or patience to draw such things.

I'm a big fan of those kinds of standalone stories, too, but it's a hard sell. I also know a lot of prose writers who love novellas, and it's a hard sell there, too.

Sure, a perfectly balanced and complete read is the best. As a reader you have no idea what direction the story will turn, surprises all the way. But you can only sell it once. Companies know that readers will invest in ongoing stories, that’s more revenue month on month. And stores prefer that as well of course, it is a safer bet.

You've made a number of short comics. Do you like making those? Or are they a little too short as far as the time and space to work?

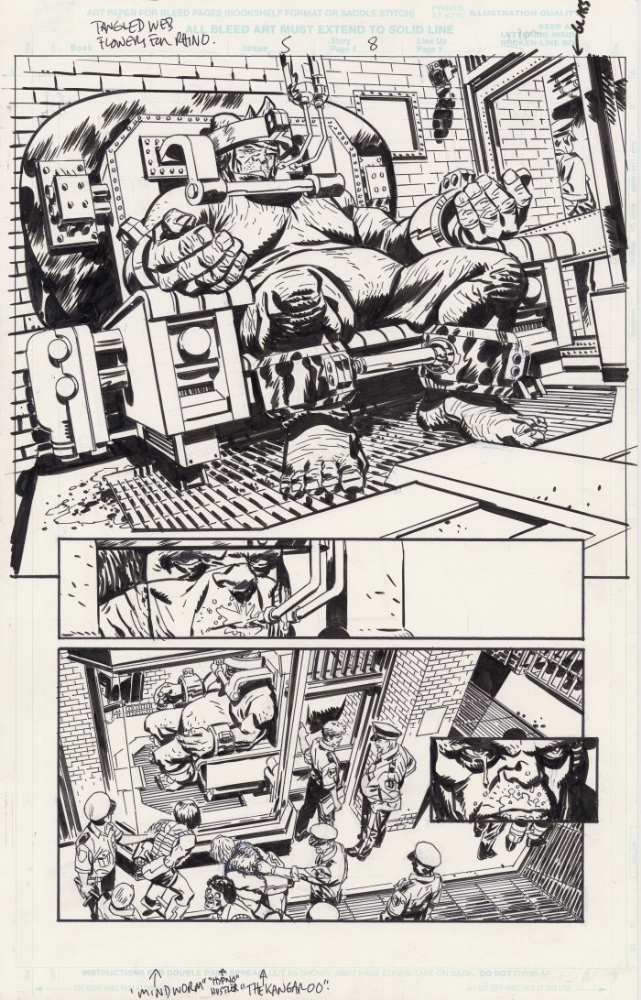

I liked doing shorter stuff like the Rhino story for Spider-Man’s Tangled Web and the "Good Monsters!" story [in Monsters on the Prowl #1, Dec. 2005] because it gave me a taste of Spider-Man and Marvel characters without having to commit to anything longer. I got to scratch a nostalgic itch and it was enough, I didn’t and don’t feel the need to do more. Fill-in issues on The Dreaming were just something to do, again, no commitment beyond an issue. They asked, the job fitted in. It wasn’t a directed choice; in retrospect I was drifting from one thing to the next. I regret that now, if I had considered that my enthusiasm would wane along the way I might have been rather more focused on being more strategic about the jobs I took on.

There’s also the matter of the time it takes to make these things. I’ve always struggled with deadlines; more recently I realized it was a lot to do with really disliking finishing artwork. I realize how that sounds, but there you go. I enjoy the process of working out the storytelling and roughing the pages out, but actually finalizing the pages is something else more traumatic. To me the pages are rarely better than the thumbnails, the layouts, the closer they come to being finished the more compromised they become, for whatever reason. On the other hand, the small experience I’ve had with storyboarding for movies proved I was quite capable at working when the finish wasn’t an issue.

Did you and Milligan work together in the same way on Face that you had in Enigma or had the process and the interactions changed over the years?

Pretty much the same process, but drawn better and with clearer storytelling! I was still faxing pencils, faxing inks as I progressed through the book. I don’t recall any changes requested by Art or Peter.

After that you did a miniseries with Nick Abadzis, Millennium Fever, which I really liked. Did you know Abadzis, either personally or just as another British comics person?

I knew Nick’s work in Deadline magazinebut I don’t think we had talked prior to collaborating on Millennium Fever. I remember prior to drawing the book I met up with Nick and Art’s assistant editor, Tim Pilcher, and we visited many of the London locations that Nick had in mind. He elaborated on what he was going for in the story, how he felt about the characters, while I took photos for reference. It was interesting, the first and only time I ever did this. I showed Nick a few pages of character designs I had drawn and was amazed when in return Nick showed me the designs he’d made; there were quite a few similarities regardless of our stylistic differences. I shouldn’t have been surprised given that Nick was also an artist, used to drawing his own comic pages. Those similarities felt good, like we were on the same page, a good thing as the story was clearly quite personal to Nick.

As you mentioned, Nick Abadzis isn't just a writer but an artist as well, and one with a different style than you.

We found despite having a different approach to drawing that my designs tallied well with his, they had an emotional, empathetic connection or solution to the criteria laid out in Nicks’s character descriptions. I was just doing the same thing I’d do with any of Peter’s scripts, responding to the voice of the character, and any explicit character descriptions, of course.

You and Milligan also made Girl around this time. Which I just reread and it's about an unreliable narrator - was the idea from the beginning that you would draw everything “straight”?

I don’t recall there ever being a specific note or discussion on how I should handle the story, it was all implicit from Peter’s script. I do have an element of cartooning to my drawing, even though I lean into realism, but if it had been drawn in a photorealistic way it would have given a very different tone to the story. Peter actually wrote the story for Glyn Dillon to draw, he drew a couple of studies for the character of Simone to accompany quite a different synopsis of the story. That may have been when Glyn left comics for storyboarding, I’m not sure.

I keep thinking some of the best comics are about voice. As an artist, how does that voice of the main character or characters help you think about the design and the approach?

For me it is exactly that. It’s why I rarely feel the need to converse more about the book whilst drawing it - because everything is powered by the voice of the character. I hear it play out in my head and it suggests not just the actions but the emotional performance of the character. You know when it works on the page because you can feel that connection to the character. It’s about empathy. There was a figure I drew in Hellboy: The Wild Hunt where this backfired. In the story, Hellboy had just lobbed an axe at Nimue, she’s collapsed on the ground in the foreground, levering herself up as Hellboy rushes her. Mike had me redraw her, as even though her back was to the reader, her body language was too sympathetic; not something we needed to feel for the villain of the piece!

And how does the voice of the story affect the storytelling? Because I’ve been reading your comics and they all look like your work, but they are all told differently in a way that, as a reader, the voice and the design and art choices are all tied up together.

I’m not sure I can separate the process, as I was just doing what felt right at the time. It really comes down to the script, what is the energy of this scene, what is the emotion? Do we need to experience this within the stage, or do we need to pull back, observe at a distance? Does this need to feel more calm, more jagged, harsh? That’s the nice thing about a comics page, in that fixed space of a page there are limitless combinations of panel layout, viewpoint, acting choices, it’s the juxtaposition of these that solve and sell the story.

During this time you began drawing covers for Shade, the Changing Man. And doing a lot of cover work in the years that followed.

I really enjoyed doing the Shade covers, I looked at it as an opportunity to be paid to learn how to paint. A few years had passed since I painted Kid Eternity and it was a chance to build on what I’d learned then. It helped I could draw better as well. Shade was a wonderful series, it gave up endless imagery to draw upon and, at least early on in my run of covers, I felt I had free rein to come up with whatever I felt made a good cover image. I avoided trying to tell a story, I preferred to try to come up up with an arresting image that would make potential customers stop and think “What’s that? I want to know more!” It got a little more controlled as [the series] progressed, more editorial suggestion, more art direction. Not that that is a necessarily a bad thing, but I did find myself submitting numerous iterations of some of the covers.

The Shade covers caught the attention of editors at Dark Horse as well; I was very happy to be asked to do some Star Wars covers though anything that contained the original characters for inevitably turn into a nightmare over likenesses. I had no interest in redrawing the same over-referenced publicity shots of the actors, I was always ideas first and [attempting to] create a likeness to fit the idea. Very stupid of me, but there you go.

For years you were mostly working at Vertigo. Was that intentional on your part? Were they just offering you enough interesting projects?

I felt no real compulsion to move on. I was very happy to work with Pete Milligan and Nick Abadzis, the odd episodes of The Dreaming were fine too. I loved doing the Shade covers, which lead to the Dark Horse covers. I had no complaints. I did get to the point later where I realized I was just filling time - and there was a point where Marvel was trying tempt me. That actually felt a little weird because as a kid that’s where my interests lay–Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four–but I realized I was comfortable with drawing the sort of stuff happening at Vertigo. A version of the real word tinged with the fantastic. I could no longer see myself drawing skintight costumes. That said I did agree to draw The Further Adventures of Cyclops and Phoenix on the condition that Pete Milligan should write it. Unfortunately when I came to read Peter’s script it was broad strokes, Marvel style. Most of Peter’s skill for characterization and dialogue was missing, I assume to be written once the art was completed, I don’t know, I never did ask Pete. I simply couldn’t get a handle on the story so I regretfully left the book. I doubt anybody else regretted my absence as I was replaced by John Paul Leon, it looked amazing, as does everything JP ever drew.

During this period Vertigo was regularly publishing anthologies and so you drew a number of short comics, some with Milligan and with other writers. Do you enjoy those short quick pieces?

I did enjoy them though they could be quite time-consuming as you end up spending a similar amount of time designing characters and locations for just 8 pages as you might for an entire issue. But I enjoyed the completeness of the stories, they were quite satisfying.

It was also the opportunity to play with style a little. I’m thinking of my guest issue of House of Secrets, it was fun to take the angular aspect of the way Teddy Kristiansen drew and fuse it with my own drawing, something I would do much later with Hellboy.

I know that you also drew a story for Matt Wagner's Grendel: Black White & Red anthology. How did that happen and what was the experience like?

I think because I was already doing covers for Dark Horse, Diana Schutz just emailed me, asked if I was a fan of Grendel. Obviously I said yes. I remember I found some of the flashback scenes hard to get into, not because they were particularly difficult to draw but I found it hard to make the story flow. I think the way Matt had written the story with a bunch of flashbacks interspersed amongst an eight-page story felt a little jarring as I was drawing it. I’m pretty sure that was all on me.

You also drew some superhero comics around this time like a Scarecrow one-shot which Milligan worked on. Are you a big superhero fan? What do you prefer drawing?

That Scarecrow story was actually written by Art Young, though I think Pete did a pass over it, not that I knew that until months later. A fun story though. Like I mentioned earlier, I grew up with superhero comics but didn’t really get to draw anything like that until much later. I was used to drawing a version of reality, it kind of fit with my sketching from life whilst at college. I don’t think I’m a good fit for superhero stuff, I don’t have that slick edge that helps sell those books. I’m not down on them at all, stories are stories, whatever the genre. I prefer drawing stories, I like good character interaction, putting drawings on a page to provoke an emotional response. I probably lean to stories with a slightly fantastical element and that’s about as precise as I can get! If I can get away without drawing cars I’ll always be happier for it.

How did you end up drawing Jay & Silent Bob?

I had been talking to Jamie Rich at Dark Horse for some time, [when] he was Bob Schreck’s assistant. One of the things we discussed was Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Jamie was really keen for me to work on this new book they had the license for, because he liked what I’d done with Girl. At that point Buffy had not yet aired in the UK, I wasn’t immediately convinced. He FedExed me a recording of a two-parter from [season two] and it piqued my interest enough to agree to do a few character studies, just scribbles really. I assumed I was approved to draw a one-shot with Dan Brereton writing, but it weirdly got nixed by the powers that be, some lame excuse along the lines of “We got you mixed up with someone else” and it left me without work. I had no back-up. Meanwhile Jamie joined Bob at Oni Press and Bob, learning of the Buffy situation, offered me Jay & Silent Bob. I really didn’t know much about Kevin Smith at that point but needed a job, it was that simple.

After working at Vertigo, and DC and Dark Horse, was working at Oni a different experience? I mean Kevin Smith was a known quantity but hadn't written comics, and Oni was pretty new.

It was essentially the same, I was still working in the same home studio, still drawing sequential pages and still FedExing artwork. Different editors, different characters, but the same process. That said, I recall the first script ran overlong, had a few of those niggles like the writer requesting cause and effect to be shown in a single panel. And huge wedges of dialogue that would sometimes leave little room for the art. Bob Schreck noted all of this over a phone call citing Kevin being new to comics, used to writing film scripts, he would have a word with Kevin. Except that nothing changed; Bob left Oni for DC Comics and Jamie took over. It didn’t really matter, I just did what I could to make the material flow as best I could. It was writing, I wanted it to work. Sometimes that meant ignoring some of Kevin’s panel directions, like pages of locked off camera shots of talking heads that might work in a film, but in a comic it becomes dull very quickly.

You mentioned a dissatisfaction with finished art and I'm curious what it was like drawing a black and white book like this. Did it change your thinking about finished work or what finished meant?

I think that was why I experimented with using mechanical grey tones, I thought it would make the art a little richer. I’m pretty happy with the results but holy crap it did not help get the work done any quicker.

I was going to ask because Jay & Silent Bob is a very wordy comic and Smith is a wordy writer. But you managed to make it work. And you managed to make the finished comic look like you and gave the book its own distinct style.

It would have been much easier to go with talking heads, just rely on Kevin’s script, but I wouldn’t have been comfortable with that.

I will say that the mechanical grey tones look fabulous.

Thanks, it’s nice to know the effort was appreciated.

Was Before the Fantastic Four: Reed Richards your first Marvel work?

Yes, it was, I don’t recall who approached me about it. The script was a lot of fun, I really enjoyed the playful riff on Indiana Jones meets Tomb Raider. I don’t think that was in the script, just how I saw it. I was really trying to pare down my art, I was looking at a lot of Alex Toth at the time. Unfortunately whoever was coloring the pages managed to completely undercut any such effort, it was rather dispiriting. I should say it probably wasn’t the colorist but whoever translated the color notes digitally. I don’t know, it’s history.

You mentioned liking Spider-Man and I'm guessing that working with Milligan and getting to draw a story like “Flowers for Rhino” was especially exciting. And fun, maybe?

As fun as these things can be. I have a knack for making everything harder than it should be…. But it really was a fun story, I really enjoyed pulling an emotional performance out of the Rhino. Such a dumb character. I did have a look to see how the character was depicted at that time but ended up referring to his original costume. He was utterly absurd but all the more enjoyable for that. Spider-Man was actually kind of dull to draw by comparison, I realized then how much my sensibilities had shifted.

How did you end up drawing Ultimate Adventures? Because at the time, the book and the whole U-Decide situation [in which readers were encouraged to 'vote' for the survival of one of three Marvel titles via sales] was... odd? And over time it's just become even stranger, I think. It also seems like an odd book for you to be asked to draw.

I was originally going to draw a Zatanna prestige book scripted by Paul Dini, more because it was Paul Dini than any affection for the character. I was actually a little disappointed when I read the script.

Was that the book the one that Dini made with Rick Mays?

Yes. I’ve not read it, I’m sure it came out great, but I don’t need to be reminded of that miserable Ultimate Adventures experience.

About that time I was offered Ultimate Adventures, then entitled "The Adventures of Hawk Owl and Woody”. There was something clunky and old-fashioned about the title I found appealing. The synopsis was a lot of bouncy fun, I found it had genuine charm - something conspicuous by its absence in the final scripts. Also absent was all that U-Decide crap, that was all sprung on me later. I hated it from the start. To my everlasting regret I turned down Zatanna in favor of Ultimate Adventures. The writer was Ron Zimmerman, a TV writer, not that I was aware of anything he’d done. Like I said, the synopsis was good, it had momentum. His actual scripts varied in page count every issue. Apparently he was too much of a big-shot writer to comply with a page count. The editors left it to me to fit it all in. Thanks a lot. He also came with character designs by someone he’d worked with in TV. They were terrible, so I rejected what I could, yet he was still given credit. It was a terrible job that just got worse. That said, I tried to draw it, still responding to the original synopsis; I tried to give it charm where I could. It’s the worse thing I ever worked on yet contains some of my favorite work. Make of that what you will.

I understand what you mean by some of your favorite work. Flipping through it, there's this two-page spread that jumped out at me as the kid is running around the Batcave–not "the" Batcave, I know, but whatever it's called–and the layout and his expressions have such energy and it's fun. And then you read the text.

I was still trying to keep it playful, but really, what was the point?

The book was also notable for being late. Were you waiting on scripts or what was behind that?

I was slow as I ever am, but ground to a halt midway through issue #3 when my mother died. I emailed Joe Quesada, who was sympathetic and said to take the time I need, so I did. I pretty much shut down. Nobody from Marvel bugged me for pages. I appreciated that in my closed down state. When I returned to work I was told that they had considered getting a fill-in and skipping me ahead to later issues or whatever, but instead, nothing. So now I was incredibly late and had to pencil for an inker, which I had never really done before, bar those few pages inked by Sean. I told Marvel it would probably take me as long to pencil as it would to ink as well, and I was right, but they got really excited by these tight-ass pencils, there was even talk of them making me exclusive; it was hilarious under the circumstances. Then the book was inked and it was so dull and lifeless. I’m not blaming the inker, he was inking bluelines of the pencils and it was probably hard to read, I don’t know. And I don’t care. Except I obviously do because it was such a waste of time and effort.

I’m sorry. It is nice that Quesada and Marvel let you have time after that. Logistically it's confusing and odd, but not everyone would do that.

I felt their intentions were well-meant even if unresolved, it was awful. It would have been better if I had just stepped down from the book altogether but it wasn’t suggested I should do so and I didn’t have the presence of mind to offer that solution. I was pretty dysfunctional.

Going from dealing with one screenwriter and having to adapt and rethink those scripts to another who didn't even bother with page limits and then having to fix all that is dispiriting. I don't even know if that's the right word, but it's a lot of work. And of course you don't get the credit for all the work and time and energy that it requires.

At least Jay & Silent Bob was a funny book, it made it worth the effort. It may have been overwritten for a comic script but that’s exactly what Kevin’s fans expect. I found a way to make it work. I doubt I could have done anything to fix Ultimate Adventures, and coming out on time wouldn’t have improved it. Well, maybe if you liken it to ripping off a sticking plaster causing less pain.

The next few years after that you didn't draw a lot of comics. Were you doing other work? Were you consciously trying to get away from comics?

I was taking on fill-in issues that came my way, treading water I guess.

I did a Tom Strong two-parter with Ed Brubaker. Scott Dunbier saw the pencils for the UA issue I only pencilled and offered me Tom Strong on the strength of it. I thought that sounded a lot of lighthearted fun so naturally Ed set about writing the darkest Tom Strong story he could! A good story regardless, it gave me the chance to play with technique, splitting the book into two distinct styles.

What else? "Good Monsters!" with Steve Niles was a lot of fun, I got to draw Hulk and the Thing along with a host of classic Kirby monsters. And the Mole Man and his short-sighted minions! That one-shot was enough to scratch another nostalgic itch. Fun to try to channel something of Kirby in my work as well, it didn’t always work but it was fun all the same.

So how did you come to draw Hellboy?

I got a call from Scott Allie, Mike’s Hellboy editor. Scott knew I was a longtime fan of Hellboy and Mike, we’d even talked in the past of the possibility of my drawing a Lobster Johnson book but it came to naught. Scott asked straight out, would I be interested in drawing Hellboy, and of course I said yes.

They wanted me to commit to three, possibly four volumes. And if I couldn’t do the first would I be willing to commit to the rest? The problem was I was already laying out the second issue of a Vertigo series written by Mike Carey. The first issue was pencilled and partially inked, and I was enjoying the work. I liked Mike’s work a lot, was happy to be working with him. I felt bad about letting Mike Carey down but this was Hellboy, I really wanted to do it. I was still stinging from the experience of Ultimate Adventures, this time I wanted to do what was right for me. So I committed to drawing Hellboy straight away. Mike Carey was upset at the time but very gracious about the situation over time, for which I’m very grateful.

So I said yes, I’m in, and then had a long talk with Mike Mignola, he pretty much laid out the whole story in broad strokes, right up to the demise of Hellboy.

Was the Mike Carey book you might have drawn Crossing Midnight?

No, the book was Faker.

I've heard a few artists say that Hellboy is one of those characters who looks simple but is very hard to draw and I'm curious about your take. What was your initial take on drawing him and how did that change over time?

I found him tricky at first, it’s hard to draw him without falling into aping the way Mike draws. That wasn’t going to work, we draw quite differently, our approach to visual storytelling is very different. I tried to blend surface elements of Mike’s drawing with my own drawing, it just developed over time. One thing I had to learn very quickly was to not have Hellboy act too broadly. Mike’s direction was that Hellboy was an old guy at at this point in the timeline. Keep everything quiet, small subtle moves, no extreme expressions. Until you need them, less is more. Ironic given my habit for crowding the panel with too much extraneous detail, but there you go.

So Mignola presented everything–that this is a series of miniseries over the next few years that ends with Hellboy's death–when you first took the gig?

Like I said, Mike told me the broad strokes from the start, it was quite overwhelming. We’d talk at the start of each series and Mike would go into much greater detail. I think he likes to tell and retell the story, it gets a little more embellished each time; I got the sense that he was making new connections as he told it, the story got ever richer.

I've been going through your Hellboys and Mignola’s and Corben's and other people’s, and they all look a little different as far as the layouts and the pacing. What did Mignola’s scripts look like and how much freedom did you have?

The first four scripts of Darkness Calls arrived in a big package along with all the collections and Library Editions, it was quite overwhelming but also incredibly exciting. At that stage his scripts were handwritten, full-page and panel breakdowns with most of the dialogue. Mike had also drawn small ink thumbnails for most of the pages, there was enough there to visualize how he would have drawn it. That was a first for me, I was used to very much going my own way. I found it hard to draw the pages as suggested because it was often counterintuitive to how I would normally visualize a page. I tend to think more three-dimensionally, like a camera moving through a film set. It often felt too abrupt if I followed Mike’s directions. Like I said, different approaches, this isn’t a criticism at all. And those silent cutaway shots with which Mike populates his pages, they didn’t work the same when I drew them. As much a fan I was of all Mike’s work I had to adapt to make it work, it took a few issues before it felt more comfortable, had a sense that we were gelling better.

Early on I did what I always did, added in panels where I felt they worked, but I think I drove Mike mad with them! I cut back on that.

At least one page each issue I would find myself redrawing layouts to get closer to what Mike wanted, usually it was something that felt off about the pacing. If I changed anything because I couldn’t get it to work the way Mike had intended, that would be a problem. As we progressed through the volumes Mike relaxed, stopped drawing layouts so much, and I think it all generally gelled better. But there would still be the odd page that would be a sticking point. There was a page near the end where I had to ask Mike draw a layout, I had taken several runs at it and it was just eating time, he clearly wanted something very specific and I wasn’t getting it. I remember asking if he ever went through this with Corben? No, Mike was too much of a fan, Corben could do what he liked! I think the other issue was the books I was drawing, they were the main storyline; regarding the other stuff Mike was more relaxed.

I was going to say, you were drawing the main story of Hellboy and not a side-story adventure, which I would imagine came with pressure for you. And I'm sure Mignola had moments of struggling with control and letting you draw these huge scenes that he’d had in his head for a while.

Yes, and understandably so. Mike did waver periodically over scenes he might want to draw himself. I recall him describing this great gag where Hellboy is staring into a mirror whereupon his distorted reflection steps through the glass and commences kicking Hellboy’s ass; on finishing he said that he’d be drawing that scene. I think by the time we got to that point he was happy to let it go, or maybe was just too busy elsewhere. Either way, I drew it. There was even the possibility of me drawing Hellboy in Hell… amazing as that would have been I’m glad it didn’t come to pass. For one thing I got to enjoy Hellboy as a fan again, and that was wonderful. Of course as I was reading it I was all too aware of all the pitfalls I would have thrown myself down had I being drawing it, Mike obviously had such a vision for his version of Hell that I would have been constantly second-guessing and getting nowhere close to the mark. I’m sure the same thing occurred to Mike so any possibility of me drawing Hellboy in Hell lasted about as long as it took for Mike to mention it in passing conversation!

Was it a different experience working with Mignola on The Midnight Circus?

Very much so. From the beginning I had the entire script. I could see the shape of the story and pace it accordingly. No thumbnails this time, I had a much freer rein. We were also dealing with the adolescent Hellboy, that was a joy after 18 issues of Hellboy facing his end, I could be much broader and bouncier with the young Hellboy’s performance. That was a lot of fun.

Was The Midnight Circus a book he wrote for you to draw?

It was written for me, I think Mike figured I needed something more lighthearted after what I’d had to put the older Hellboy through.

Everyone seems to enjoy young Hellboy. After spending all that time on Hellboy and getting him just right, was it easy to nail his younger version?

Prior to embarking on Midnight I drew a sheet of studies of the young Hellboy. I was actually on vacation with my wife in Greece, relaxing with a beer on our balcony, doodling in a sketchpad. I’d looked at Mike’s version of course, and used that as the basis of what I drew, but I just pushed the elements of him being a young boy. With both the older and younger Hellboy I tried to make them feel organic, naturalistic, but keeping the proportions that Mike established for both. I wanted to avoid them looking like a young boy or a man with a load of prosthetics stuck to their faces. I’m hoping eventually we’ll get a Hellboy movie where Hellboy is entirely animated.

The Midnight Circus is a gorgeous book. Honestly, one of the best things you've drawn. And it felt much more like you pushing your style as opposed to the earlier Hellboy stories. I don't know if that's how you approached it or feel about it.

Thank you. I decided from the start that I would play with style a little, there’s a transition as Hellboy steps through the stone wall that I saw play out in my head even as I read the script. I’d been playing with line and wash for a while and thought it would suit the dreamscape of the circus and its inhabitants. That shift in technique definitely brings out more of me I think. The young Hellboy is a livelier character, I could let him act and react a lot more broadly. The book was delayed a few months because I got to draw storyboards for Darren Aronofsky’s Noah. I had drawn around 18 pages of thumbnails at that point. Returning to The Midnight Circus was quite tough; I had spent months drawing rough boards, it was quite liberating, so going back to drawing finished art was tough. That said, I believe the change was good for me, I came back with a fresh eye and really enjoyed playing around with style and technique on Midnight. I think it still stands as my favorite work on Hellboy.

Young Hellboy is more expressive, and so going from the heavier lines and inks on adult Hellboy to the wash in The Midnight Circus really gave it a different feel. You talked earlier about voice being so key in how you think about comics, and you can see the result.

The line and wash certainly added to the dreamlike quality of The Midnight Circus, but I don’t think the rendering technique makes much difference to the character; both the traditionally inked young Hellboy and one drawn in line and wash feel essentially the same. That was more about differentiating between the “real” word and that of the Circus.

I was really very happy with the line and wash work on Midnight Circus but the downside was I saw a few people crediting Dave Stewart for the effect, as if he had painted the art; it was a bit frustrating. Dave is always great of course, he handled the coloring of all the varied styles of the book a little differently. We found it worked best if the color on the wash pages was more desaturated, less intense.

You also drew a couple issues of Books of Magick written by the late Si Spencer at this time. Did you and Spencer know each other?

I knew Si a little from chatting at parties and conventions, he was a lovely guy, full of great stories. Somehow I forgot I agreed to draw two issues [#6 & #10], they weren’t consecutive. I drew the first, then had to rush the second as I was involved with something else, I forget quite what. So that explains the second issue.

You mentioned drawing storyboards for Noah. Have you done a lot of storyboarding? Is it something you like?

I haven’t done a lot but I do enjoy it. Apart from Noah I did a few months' work on a Pixar production that was sadly shelved and a few weeks on Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. Three entirely different experiences, I’m grateful for them all. It was good to be drawing something other than comics, it gave me a little perspective of life outside of comics.

I think my favorite part of comics is the problem-solving aspect of telling a story. Once you get past that and the initial rough drawing the rest can be a be a bit of a grind. Once I get to that point, in my mind the job is done. The reality is there’s a lot of refining to be done, redrawing, inking, it gets repetitious and each stage, while it might get more refined, it also loses a little life. So often the rough layout is better than the final page, the closer to being finished art it is, the more compromised the art becomes. This isn’t always the case, but for me it all too often feels like that.

I would think that storyboarding would be something you'd enjoy, especially given your comments about finished artwork. Is this something you actively want to do more of?

It would depend on the circumstances, really. There were a couple of projects I had been contacted about but COVID happened and that was that. It’s not like I’ve pursued storyboarding, I’ve been fortunate that the jobs I’ve done have been offered to me. But yes, I’m interested in doing more.

In 2011 you were one of the people at the Kapow! convention in London who made a comic book on stage. How did you get involved with that? Did you and Mark Millar know each other before that?

I knew Mark to say hello to. We’d met at cons over the years.

I think Mark just asked me, I must have been in a weird mood when I agreed because it sounds like my notion of a nightmare! We weren’t actually on stage, just sat around a couple of tables at the side of the con floor. We had allotted times to sit and draw, I found [myself] next to an equally hungover Frank Quitely on the Saturday morning. We could just pick any panel we liked, I picked the panel before Frank to give mine some context; that and there were no figures, just an apartment exterior or something. I’d foolishly chosen the opening panel and did a very poor job of it!

How did you and Millar end up working on MPH?

I had just arrived at Tommy Lee Edwards’ family home when I received Mark’s e-mail pitch that we should do a book together. I was feeling more than a little punchy after an awful delayed flight but it sounded good to me. I think Mike would happily have furnished me with more Hellboy to draw, but I was aware that I needed to have ownership of my work. Something that could potentially have a further life that would be financially beneficial. I was already thinking that, and here was Mark offering just that possibility. If I hadn’t liked the story I wouldn’t have drawn it, but that wasn’t an issue, I loved the premise and it flowed so well.

So when Millar pitched you and said, we should do a book together, did he pitch you MPH or did he have a few ideas? What appealed to you about the story?

No, it was MPH from the start. I think he had in mind the way I drew figures in earlier Vertigo books. They weren’t exactly in fashion but he felt they had an energy to them that would translate well to MPH. If I remember rightly MPH actually started life as a book intended for Ashley Wood, I think it was called Run then.

The characters aren’t obvious hero types, [they] do questionable things to get by, but in spite of that, desire to better themselves. Or not, as the case might be. Throw in a little Robin Hood and a little time-travel, I just found it very appealing.

Talk about finding the right approach to MPH, because you manage to give that energy and this kinetic sense that so much of your work has, but it has a different approach in some ways and is a little slicker.

I think I was really just leaning into what Mark saw in my previous work. I rarely draw a character completely at rest, I always try to give an impression of the body in motion, even in small moments; the sense of a figure shifting their center of balance from one foot to the other, or twisting, gesturing, whatever it takes. I’d treat the super-speed stuff exactly the same, it seemed to work. The slicker finish you detect is because I drew and inked the book digitally. I was hoping to speed up my process and so purchased a Cintiq. I can’t say I really drew any faster, just found new ways to add detail and procrastinate, but the line did become slicker as a result, which I actually regret. That said, it’s just as well I went digital as by the time I drew the final issue I was essentially blind in my right eye thanks to a cataract. I was at least able to compensate by zooming in on the artwork; not ideal, but I couldn’t have continued drawing otherwise.

Now that you've been using the Cintiq for a few years now, has it sped up or changed how you work?

I’m definitely not any faster, but the Cintiq has become part of my process. I like the lack of erasing real pencils, the ease of recomposing elements of an image rather than having to completely redraw the whole thing. Of course you can tweak work forever as well, that can be a time sink...

Have cataracts changed how you work or how you can work?

Yes, I find it easier to draw with unimpaired vision! Following MPH I was booked into surgery, but before it took place I made an MPH sketch for a convention auction. It was the first physical art I had made in a while and was incredibly difficult, I found it so hard to ink and focus with what I considered my weaker eye. Both of my eyes have had surgery since, but I still at least pencil digitally. I remember my optician informing me of my first cataract forming many years before, he said it was likely caused by years of inhaling steroids for asthma. I was floored by this, I’d never been warned of such a side effect. "Hey kid, here’s drugs for that crap breathing all your life, as a bonus it’ll fuck up your eyes later as well."

Millar had been making a lot of Millarworld books by this point. Did he and Peter Doherty and whoever else have a system in place that was pretty typical as far as making comics?

From my point of view it was no different to drawing any other book. With the exception I was drawing it digitally, of course, but that was my choice. It still came down to drawing and storytelling.

You mentioned before about a habit of crowding the panel with “extraneous detail.” Will Elder famously called those details "chicken fat", and I'm just curious where that urge comes from. What do you like about it as an artist and a reader?

I’m at a loss to explain it, it happens despite my best intentions of producing more stripped-back work. Ideally you want the work to read quickly and easily, everything arranged to propel the eye and story forward. On the other hand, if all extraneous detail is stripped away it can be a little clinical, the world becomes less believable. Life is clutter. I find myself populating the panel with details that tell you about the environment. And it all takes time, of course. The crazy thing is that when time is short, rather than stripping back that detail I pour more energy into it, it’s never a good sign. When I was in my late teens I became aware of the Pre-Raphaelite movement via Barry Windsor-Smith, I think that may go some way to explaining my habit of over-detailing. Maybe.

You said that one reason you drew MPH was ownership, and you're looking to have more ownership and control over your work. Is this one reason why you haven't been making many comics recently? Have you been taking a different approach to thinking about your work and career?

I decided to take time off because MPH afforded me that opportunity. The sale of Millarworld to Netflix allowed me the time and security to step back from things and consider what I wanted to do next, rather than just take the next thing that came my way because I needed to pay the mortgage.

Of course the next thing that came my way turned out to be the chance to work for Pixar, and I wasn’t going to turn that down. For the first time ever I didn’t need the money but I really wanted to work with Pixar, I relished the opportunity.

Almost immediately after that I broke my ankle and that resulted in most of the year being wiped out. I spent most of my time flat out with my foot in the air, watching crap TV and doing little else. I couldn’t concentrate to draw, it wasn’t great. The last couple of years of COVID haven’t been great for anybody. My wife lost her father to it and contracted COVID herself right back at the beginning; that developed into long COVID and she’s still dealing with it, fortunately doing much better now. I drew a few pages and covers but not much. I am finally drawing another miniseries but it’s been slow going. Still, it’s looking okay, I think. As for what’s next, well, that’s the question, isn’t it?

The post “The Closer They Come To Being Finished The More Compromised They Become”: An Interview with Duncan Fegredo appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment