Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

-T.S. Eliot

To some, Jim Woodring's latest book, One Beautiful Spring Day (Fantagraphics, 2022), may be viewed as simply a reprinting of three of his previous books... plus some other stuff. And, technically, that's exactly what it is. OBSD collects each of the 100-page stories found in Woodring's Congress of the Animals (Fantagraphics 2011), Fran (Fantagraphics, 2013) and Poochytown (Fantagraphics, 2018), and weaves them together with 100 pages of new material.

But... it is so much more than that.

The "other stuff" Woodring has added to the mix does much more than simply connect three excellent, previous-published pieces featuring his signature character Frank. It deepens those existing stories, gives them new meaning and allows for additional interpretations of works whose meaning and interpretation were already up for... discussion. Ask me what happens in One Beautiful Spring Day—or any of Woodring's work—and I can do my best to explain what I think happens, but I'd be better off explaining how it makes me feel. He is not a storyteller whose stories are easily described. He is more like an ancient architect designing landscapes and buildings whose finished pieces, while seemingly familiar, remain alien and puzzling. They come from some time and place that exists just on the fringe of a fevered dream world. Or just behind the curtain of reality. Any time I think I'm beginning to decipher the code, we're off in another direction and I realize I'm reading a language that I only thought I understood.

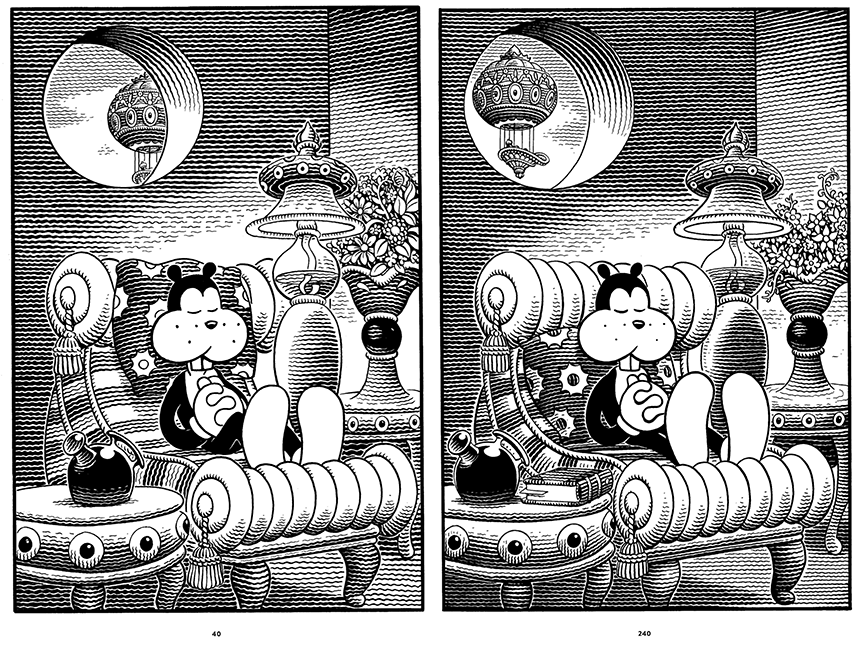

Using black and white drawings that shimmer and pulse with tingly wavy lines that evoke the wordless woodcut novels of an earlier generation, OBSD is in many ways a typical Frank story. Cast in the Joseph Campbell "Hero's Journey" role, Frank embarks on adventures and faces (harrowing) challenges. But rather than following Campbell's model where the hero "wins" and returns victorious, Frank merely survives and returns unchanged. He remains completely uninformed or enlightened by his experience; the same cannot be said for the "reader" of these wordless tales. Or, at least, this reader. In OBSD, Woodring takes all of his many artistic talents to a completely different level. And that's a bit scary. There were times while absorbing OBSD that I felt as if the book was actually a living entity. Breathing. Vibrating. Waiting patiently. It's the "widening gyre" that Yeats describes in "The Second Coming".

"The artist has always used his or her inner 'stuff', the very substance of the soul, mixing it with the subject's own essence and deriving droplets of imagery from this alchemy," the film director Francis Ford Coppola wrote in his introduction to Woodring's The Frank Book (Fantagraphics, 2003). "Jim Woodring has taken the time and trouble to master the cartoonist's craft in order to express his vision of the universe in a way that any person in any culture can absorb. It is difficult to imagine these tales being told as well in any other medium. As for exactly what it is they are saying, that is something readers will have to discover on their own. The events that unfold in these stories are nearly impossible to explain; yet on some level we understand them."

Do I understand everything that happens in One Beautiful Spring Day? I do not. Does that matter? Not to me. Even its author, as he says in the interview below, is unclear about the meaning of some of OBSD's content. What is important to me is the feeling of awe and sense of wonder the book evokes in me. I know it is one that I will continue go back to again and again. Each time that I have, that wonder has deepened.

Like all of his Frank stories, Woodring developed One Beautiful Spring Day under the direction of the mysterious force he calls the Unifactor. According to Woodring, the Unifactor dictates what is to happen in the Frank stories and he simply draws them. And if he goes against the Unifactor's wishes—which Woodring did in Congress of the Animals—the results will be disastrous. Or maybe not. If if wasn't for the "mistakes" made in Congress, there would be no OBSD.

And the world would be a lesser place.

This interview was conducted through a series of many, many emails over the course of several weeks in late summer and fall of this year, and focuses primarily on the process of developing One Beautiful Spring Day and defining what, exactly, the Unifactor really is. Or something like that. A thorough account of Woodring's early years and work prior to Frank can be found in this lengthy interview he did with Gary Groth for The Comics Journal in 1993.

* * *

JOHN KELLY: A few years ago you said something to the effect of… you could look back at your life and feel like you've accomplished what you wanted to. Which must be a good feeling. And certainly, given your astonishing body of work up until that time, it was certainly a fair statement. But now, with One Beautiful Spring Day, it seems to me that you've gone to another level entirely. Do you feel like you've passed a new bar with this book?

JIM WOODRING: Did I say that? Well, in a sense it's true... I set out to be a cult artist and I feel I've done that. And that does give me some satisfaction, but of course it isn't much in the larger scheme of things. OBSD is a milestone for me, but less as an achievement than a platform of understanding. I turn 70 in October and feel a strong disinclination to continue as I have been doing. For all I know there may be no more Frank stories... I haven't felt any recent stirring in that direction at all. There are so many things to do. Aside from the looming deadline the future teems with promise.

The Unifactor is both the world in which Frank lives, but it is also a guiding spirit/teacher/force that informs the direction your Frank stories take. If I'm imprecise with this interpretation, please correct me.

That's accurate. Like every other aspect of Frank's world the name the Unifactor simply presented itself, quietly and assertively, as the name of that world. Years later when I began to tussle with the guiding light of the Frank enterprise I thought of that entity as the Unifactor as well, mostly for convenience's sake.

At what point did it occur to you that it might be a good idea to try to combine three different existing books into one new long story? Or did it even "occur" to you? Is that even a relevant question? Was it just something that the Unifactor instructed you to do?

Well, the three books at the core of One Beautiful Spring Day (Congress of the Animals, Fran and Poochytown) were all atypical Frank experiences. I had begun drawing 100-page books, beginning in 2010 with Weathercraft. That script came in the usual way; I put myself in a receptive mood and wrote the increments of the story as they popped into my head, keeping the ones that had that subtle fizz which signified viability, putting down one sentence after another until I had a complete description of the action. And like almost all previous Frank stories, the structure was formulaic in that it ended with equilibrium restored, told a specific finite story and had a discernible moral or overall point.

When I began the next book in 2011 it was originally to be called Poochytown. When I had the script in hand I didn't like or understand the story. Which had happened in the past, but I'd just gone ahead on anyway. This time I allowed myself to demur, and for the first time in my dealings with Frank I made conscious changes to a Frank script for my own selfish reasons.

I thought it would be good if he left the Unifactor and saw some other places; and while he was at it, he could find a companion, a mate, who would come live with him and share his future adventures. That interested me, so I re-wrote the script. It was a struggle; the Unifactor simply withdrew from the process and it took months to work out that storyline.

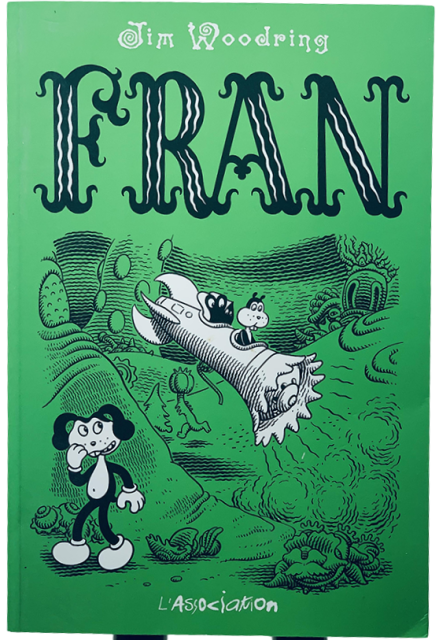

And truth to tell I liked the story a lot, and enjoyed drawing it. But when the published book [Congress of the Animals] was in my hands I realized I'd committed a huge blunder. Adding Fran to the picture changed the dynamics utterly. Frank was suddenly content. He slept in, drew landscapes for a hobby.

I'd thought that Fran had arrived to stay but I saw she would have to go. And it turned out that the Unifactor had anticipated this; the solution presented itself in one big piece. In fact there were now-evident foreshadowings of this solution in Congress.

So I drew the book Fran, and she was gone. Then I re-undertook Poochytown from scratch. I had to redraw the opening five pages of Congress line for line to make apparent that this divergent story opening looked like Congress', but was entirely different. Crazy, I know.

So I worked up Poochytown as dictated, and got a story with every requisite of the formula in place except for the clear point and/or moral. In fact the morality of Poochytown was disturbing, Manhog had been unforgivably wronged, and Frank's carefree repose at the end seemed entirely unjustified.

So those books were not intended to be sequential. The title page of Fran says, "Continuing and preceding Congress of the Animals" and the title page of Poochytown says, "Discontinuing Congress of the Animals and Fran." I didn’t really know what was happening.

When I set out to do the next book the structure of One Beautiful Spring Day presented itself entire, a vast idea swaddled in a cloud of events. It took me a few days to gather and organize it all but when it was worked out I was overwhelmed at the way it had come together, the way everything fit, even the way my lame screwup with Congress had been transmuted into a glorious story catalyst, an artistic masterstroke. And as I saw all the disparate things come together to form a single well-defined but complex and relevant metaphysical fable I was absolutely dazzled.

In order to combine the stories, you added an additional 100 pages to the existing works. How difficult a process was this?

Getting the page count to be exactly 100 pages was difficult, especially regarding the timing of the sequences. I try to control the relative reading speed of sequences by putting in either more or less information. Some scenes I want to be read briskly, some I want to be more ponderous, or quiet. I don't know if it actually works for readers but that's the goal.

When you were working on the three books that now comprise One Beautiful Spring Day I assume you thought of them as separate stories. Now they are part of one bigger one. Do you think the Unifactor knew all along that it would eventually turn out this way? Do you suspect that the "mistake" you made with Congress was all part of the Unifactor's big plan? Maybe a test, even?

That's a question I can't answer. The coming together of OBSD belongs to that category of experiences wherein things line up or work out in such a way that one has to wonder in grateful astonishment how such a fortuitous, seemingly pre-ordained result could occur. I don't actually believe the Unifactor is an independent, controlling agency in any real sense. But on the other hand I really have no idea what's going on here.

I know that you drew, and redrew, some of the pages in One Beautiful Spring Day multiple times because of various reasons. For some pages, the recreation of the pages was part of the story's arc. But for others, there was something about the page that you felt was not right. Was the Unifactor also guiding you in that process? Like, letting you know when a page was acceptable and not?

Often I’ll finish a page and then see how it could have been done better. Sometimes I let it go, but if the scene is important I'll re-do it. One thing about the actual drawing of Frank stories is that it is a lot of work but very little struggle. The drawing goes smoothly, with almost no emotional involvement. If I decide to redraw a page I just immediately get out another sheet of Bristol and start over in complete serenity, without any anger, anguish or frustration at all. Like a spider rebuilding its web. Not my usual way of doing things, I assure you.

Did you find that you had to redraw any of the old pages in order to change and adapt them to the overall storyline?

No, they were left as is.

I would think that drawing hundreds of pages of a wordless story—even drawing one page of one!—would be extremely difficult. Do you think this process was made even more difficult given that the Frank universe is wordless? Or did that make it easier given the there’s no written dialogue?

Well, drawing a story without words is indeed more work. There are numerous places where I want to show that time has passed, and since I can't have a tag that says "NEXT DAY" or "LATER…" I have to draw two or three panels of the same vista showing night falling, or showing the positions of shadows changing to indicate the passage of time.

But there is a strange heaviness to wordlessness. There's a two or three-page scene where Frank and Fran have a conversation at a table in Fran's Frank-shaped house. You can get a hint of what Frank is saying by his histrionics, but the "silence" gives the scene a solemn depth. There are other effects specific to wordlessness as well.

You have said that you chose to do the Frank stories without dialogue, at least in part, to make them universal. For one thing, they won't have to be translated when sold overseas. But is that true? Did you actually choose that, or was that how it was presented to you by the Unifactor?

The first Frank story popped into my head as an entire concept - story, cast, rendering technique and wordlessness, so I had the template with that.

Early on, before I realized the extent to which Frank was not a product of my conscious mind, I toyed with the idea of introducing language, but soon realized it would be a bad idea. For one thing, there are so many things in the stories that don't have names. And would having Frank say, "Look, Pupshaw! Jivas coming out of the ground!" enrich the experience? No.

I did experiment. I made sketches of Frank talking in flowery language, in a specialized argot, in filthy devil double-talk, and so on, but none of that worked at all. So in my mind at that point I did feel that I had chosen not to have words. But as you suggest it was the Unifactor's idea.

There is no verbal "talking" in Frank's world, but is there any sound at all? Is there music? Do you "hear" anything when you read your own work?

I can hear the world, yes. Natural sounds, animal sounds, insect sounds. I can hear the frogs droning in the evening, I can hear Frank making little "huh" noises, I can hear Manhog eating, I can hear Whim breathing, I can hear the Pups making a wide range of interesting noises.

I wonder about Frank and his existence in that Frank universe. Is he native to that universe? There are a lot of strange things in that world, but in some ways Frank may be the strangest of them all, if only because he is the most "normal" or human-like. Manhog kind of fits that definition too, but he's in some ways more like an animal than a human, and there are others like him. There are no other beings "like" Frank in that world, especially when we learn that his female companion Fran is much, much more than she appears. Frank is... pretty normal. He acts as a guide to that world, but was he placed there? Where did he come from? Do things reproduce (in the traditional manner) in the Unifactor? Do they have parents? Are they born?

My take on the situation is that Frank lives in the Unifactor at the Unifactor's behest. He has been given housing and furniture, and baskets of food show up on his table. His house changes to accommodate his needs. He's like a lucky child, supported, cared for. He exists only to explore his world, [to] see it, and play with it. And he is central to this project. I can imagine the Unifactor without any of the characters but him. If he is gone, the Unifactor doesn't operate. He is the one the powerful demigodling pups have made themselves subservient to, the one the massive goddess Fran was interested in, the one whose distress the magician responded to, the one Manhog seeks companionship with. And Frank offers nothing, has nothing, learns nothing, does practically nothing. He is good or bad completely by whim. He has no consistent moral compass, no dependable empathy, no real personality. He is the experiencer.

There is sex in The Unifactor. The Pups have had on-camera sex. Frank and Fran at least experience sexual attraction to each other; they blush at the sight of copulating dragon halves. Frank assists at the breech birth of twin jivas and is rewarded with full-body fellatio. So there is sex and birth and whatnot. But there is also spontaneous generation, budding, division, etc. In Pupshaw's first appearance she disgorges a horde of mini-Pups. And so on.

Ok, because I do have a sense of Frank being somewhat separate from the rest of that world. For one thing, he's one of the only characters drawn in that classic cartooning style. Fran, the Pups and the Pa character(s) would be the others. The other characters are drawn in a much more realistic style - or at least realistic for someone who could see inside of your head, maybe? But that different drawing style also separates Frank from the world he roams around in and amplifies the strangeness of the stories. I assume that dichotomy is done for effect, but was this something that evolved as you did more and more Frank stories? In the very early ones there are more "real world" images. There are some notes written in English, cars, things like that. A bicycle!

All that's true. Frank and the other characters you mention are drawn in line only, without any texture or shading. This comes from my seeing Frank as a pure cartoon character. No doubt the impulse to create Frank came in part from the desire to create something as potent as Bimbo's Initiation, or as mysterious and pure as the drawings of Harrison Cady, with their clear, purposeful, open-handed linework. Yes, Whim, Manhog and other characters are rendered and less cartoony. They are different in some way. In the case of Manhog it may be that he really doesn't belong there, that he is trapped in this place which is inhospitable to him, and that's why he is so miserable. If I do another Frank story it will be to liberate Manhog.

The stories did change, stylistically and thematically over the first few years. Objects from our world occurred more frequently in the early stories, but they were usually presented as things that didn't fit in. In Frank's Real Pa [Fantagraphics, 1995, collected in The Frank Book] Frank and Manhog wrestle crazily over a gun, a pistol, a Saturday night special. Why is it there? The gun goes off and it's just luck nobody is killed. At the time I drew that sequence, I thought it was odd that the gun was there; but there was a bicycle there, too, and the implication was that they had both been put there. By whom? In a way this makes the bike more scary than the gun. A gun is an obvious potential plot device; you can see why it would turn up and then go off. But a parked bike that ought not to be there? Brrr.

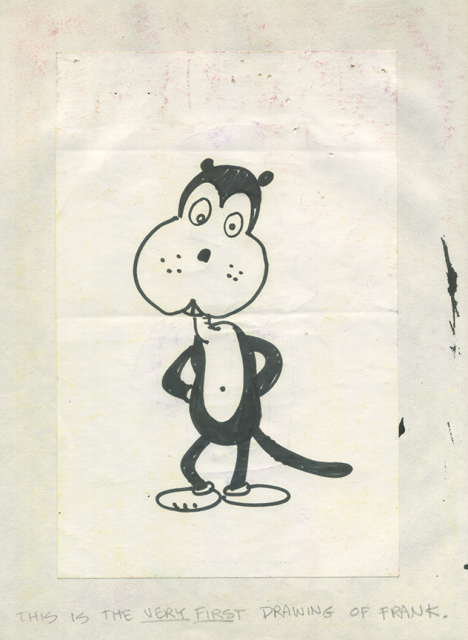

Frank changed too. Primarily, his eyes became the same size and his proportions became quantified. But even so I never, or rarely, have the sense that I have captured him in a drawing. I don't really exactly know what he looks like, or what his real name is, if he has one. In fact all the characters and the landscape itself changed a bit over the first few years.

Another element that produces that "strangeness" and adds a level of tension throughout your Frank work are those wavy lines you use for shading. No cross hatching or anything else in these stories. That effect, and the fact that it's all in black and white, gives a life to the panels. At times a sinister life, but there's a twitchiness to it, almost like it's shimmering. When you first started using that drawing style—because you don't always; some of the early Frank stories were in color—was that the effect you were going for? Those wavy lines appear in some of your other work as background, but I don't think to the extent that they do here, especially in OBSD.

The wavy lines in Frank were there from the start, though they were a bit varied in their application and execution as I figured out how to use them. You can see experimentation in some of the early stories, trying to understand and master those lines. I thought they should have some sort of personality, create some sort of "vibe", and for a long time I would very very minimally write prose into them. Thinking of them as streams of words did affect their shapes a bit; far too subtle to read, but there. And yes, I use them in other work, as my default tone-builder.

Can you try and describe exactly what the Unifactor is to you? I'm assuming it is something that exists in your personal consciousness, but do you think it is something that someone else could (or does) experience?

The Unifactor is part of me, of course, but what that means God only knows. I would love to know if other people perceive it in the stories.

Well, some people say that they do, or at least say they are guided in their work by another force. Some artists say that they believe that they are just conduits for the art they create, that the work rises up from some place inside them. Some think of art to be like a spiritual experience. Is this the type of thing you are talking about?

This gets difficult. I've never had a spiritual experience from a work of art, but I've been put into altered states by some things. Eraserhead melted me into a puddle... it took me ten minutes to crawl out of the theater. It so directly, perfectly and aspirationally nailed my own sense of how to poetically express the utter strangeness of life and the profound attraction of scary oddness. But if I analyze that I see that it isn't the film that thrilled me, it was something in me that the film activated. It made something in me fluoresce in response, in reaction to this great knowing artistic creation. That fluorescence, which of course is just a metaphor, is a kind of bliss, something you want to get close to. But it's in me, not the art. As they say, art is like drugs; it will show you places but it can't take you there.

The Unifactor could be the author/director. It could be an organizer, bringing unconscious thoughts together to address some deep, inaccessible crisis. Something like a spider, something like a flower. Some reductionists say that consciousness doesn't occur until a brain comes along to generate it. Seems like a stupid idea, but if that principle is true maybe the Unifactor is a subtle brain that put itself together and the Frank stories are its self-generated conscious thoughts. That would explain a lot.

Well, T.S. Eliot said something along those lines in his essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent". He said the artistic spark comes when "a bit of finely filiated platinum is introduced into a chamber containing oxygen and sulfur dioxide…. The mind of the poet is the shred of platinum." Meaning the artist is the catalyst, but without the viewer/reader, the artistic spark does not happen. Wallace Stevens, who did attribute his artistic guidance to his God, called that inner voice his "interior paramour". You bring up Eraserhead, which is interesting. I've heard people say that you are able to express your personal inner world so fully that the only other artist they can equate the experience with is early David Lynch, before his self-indulgence took over completely. I think there are some others, maybe musicians, who have achieved this, but it’s a singular vision. Could you ever see your work expressed in another form? Like film, or animation? I know there have been some short Frank cartoons. How involved were you with those?

"Interior paramour"... that's nice. The title of Stevens' collection The Palm at the End of the Mind affected the drawing of the sequence near the end of OBSD in which Frank experiences different levels of sleep and memory; in fact the palm itself makes an oblique appearance.

As you say, the Unifactor is "part of" you. And the Unifactor is also the world Frank lives in. So, in that case, that would also make Frank "part of" you. What part would that be? Are there things about Frank that you deeply identify with? Parts that repulse you?

Well, this all gets rather squishy. At this point I see Frank as a teaching tool, a means of conveying information to me, personally. Yes, I see myself in him in some ways, especially his drive to go and find out. I do identify with that. And I have to admit I share his faults, or some of them anyway; thoughtlessness, selfishness, obliviousness, naïveté. I identify more with Manhog, though, because he thinks more than Frank does, and he wants to and does change. Plus I look more like him.

Unifactor, or "uni - factor" literally means "one factor", or one thing or circumstance that lead to an outcome. How close is that to what it means to you? Or - how did you come up with the term? Did the Unifactor, itself, tell you what it was called/named?

My recollection is that it occurred to me when I was working up a set of Frank trading cards for Brownfield Press in the '90s. I thought I’d include a card of the world itself as a character, and the name the Unifactor suggested itself right then. It's a great word and it has obvious profound implications, but at the moment it presented itself I didn't think about that. It just was. What is it? The Unifactor. Perfect. Thanks.

So, the Unifactor named itself. Did it also give Frank his name? I seem to recall you telling a story that Frank's name came from another source.

Frank was named by a former girlfriend's mother. She saw a drawing of him and said, "You have to name him Frank!" So I did.

Does the Unifactor guide your choices in any other aspects of your life, beyond your art work? Can you visualize it? And, if so, what does it look like to you? Have you ever drawn it?

I think I draw the Unifactor in every Frank panel and picture. But it is specific to Frank. I don't deal with it anywhere else in my life. But then again… with One Beautiful Spring Day I have come to see that the peculiar resonance of the Frank stories has a more profound significance than I've previously been aware of. I'm kind of spooked by it, in fact. There are deep messages… a hidden sentence, even. It's very mysterious. So maybe it is not a separate entity in any meaningful way.

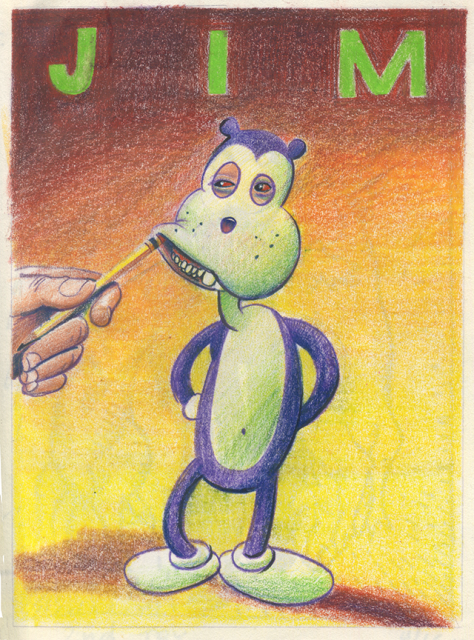

I've been familiar with your work since your early self-published issues of Jim—we use to trade 'zines back-and-forth with each other—and I've always loved your work but I haven't always understood it. Which isn't really that important to me. I don't feel like I necessarily have to fully understand a work of art in order to enjoy it or be moved by it or be astonished by it. How important is it to you—and I'm not talking about your own work here, because we will get to that later—but how important is it for you to understand a work of art in order to enjoy it or be moved by it?

I agree entirely. Mystery is essential. It isn't a matter of understanding, but of something in you being stimulated into a state of arousal that feels new and thrilling. Knowledge extinguishes the flame of curiosity. I'm more than a little leery of explaining too much about OBSD, but there is so much specific, unintended information in there that I find it fascinating, and fortunately the explanations raise more questions than they answer, as we have seen in this discussion.

So, do you ever draw a page, or story, or even just elements of a panel, because you were compelled to draw it, and not really know what it means? Only to later have a realization at some point later of what it represents?

Well, by the time I draw the actual final pages I have everything worked out to a fare-thee-well in layouts, so for the final art I don't do anything spontaneously. There is always a script-based idea first. But I often don't know why I'm drawing what I'm drawing. There is a scene in the Congress section where Frank discovers a miniature of his new house, with Pupshaw and Pushpaw inside, both looking glum; they miss Frank. Frank doesn't understand why it's there, in [Fran's] house; Fran doesn’t seem to understand why it’s there either; and neither did I. But with the next book it became evident what that miniature house meant and why it was there.

Very often I've drawn stories and not realized what they were about until much later. When the meanings do become clear it turns out they are often shockingly unambiguous.

Can you give some examples?

In Frank's Real Pa, which was originally done for The Millennium Whole Earth Catalog, Frank is captivated by a rug. The story is inexplicable until you realize rug = drug. Read with that in mind and the story snaps into sharp focus. Entirely unintentional. That's one.

Are there any elements of OBSD—part of the story or an image—that remains a mystery to you? If so, can you give an example? And, again, if so, do you assume its meaning will become clear at some point in the future?

There are some sequences I don't get the meaning of for sure. One in which Frank and Manhog find an abandoned bungalow and Frank goes in the window and explores the vacant house. I don't know what that's about. There are a number of things like that. Whether or not I'll ever get it, I cannot say.

At what point in your life did you first encounter the Unifactor? Can you describe that experience?

I guess that would be when the notion to create Frank appeared in my mind during the late '80s. It was a persistent urge to develop a cartoon character; not an anthropomorphic cartoon cat or dog or mouse but a sui genesis cartoon character. Years later it presented the first Frank story entire, and we were off to the races.

I was recently looking through some of your older work - including your very early work in the self-published issues of Jim. A lot of that material was mostly text. It's interesting to look at, given that for some people, maybe most people, you are seen as someone who writes stories without words. Do you want to go back to doing some stories with words? And is this another function of the Unifactor? Does the Unifactor "speak" to you in words? Or is it more of an intuitive force that is bestowed upon you? Does it "speak" to you or does it instill images in your brain?

The Unifactor is specific only to the Frank stories. Sometimes it does speak in words, when I'm writing down the scripts, and it also drops entire concepts at once. But I don't encounter it at all when I'm doing other work.

All that old Jim work, the autobiographical stories, the dream stories, the bizarre fables, all the comics with words and dialog come from my conscious memories and impressions of experiences, dreams, hallucinations and so on. Doing that work is a struggle… writing and re-writing, groping for ideas and clarity… the usual ordeal.

I would like to do some comics with words again, and in fact I've developed a few concepts over the years. I have characters, settings, ideas, lots of sketches and even a few fully worked-out stories, but I can't bring myself to commit to any of them. I used to just do things like that without thinking about whether the effort would be worth it or not. Now I want to make sure I won't be investing all that time and work in something mediocre.

You are a spiritual person. How much does the Unifactor play into your spirituality? How connected is it to your own spiritual sense of yourself?

I realize that the Unifactor is part of a game I am playing with myself. It does tell me things, it does show me things, and with OBSD it has actually given me some valuable, generative insights into my situation. But again, I know it's me.

Can you explain what that spirituality is for you? Is it a certain, established religious sect? And how did that enter your life?

I have an innate mystical bent. Spirituality has always been the main interest of my life. I spent my teens, 20s and half of my 30s unsuccessfully seeking a religious philosophy and practice and finally found it in contemporary Vedanta, which embraces all the classic approaches; contemplative, devotional, karmic and so on. If anyone is interested, Sarvapriyananda's talks online are loaded with information and insight.

So, when you did your non-Frank stories, specifically the earlier one with your Jim character, the Unifactor played no role in how the stories unfolded. In some ways they are personal stories, but they're also fantastical. They're not American Splendor. An awful lot of pretty weird stuff happens in them. Are some them based on your dreams?

Those autobiographical stories are all based on experiences I had, either in waking life, dreams or in childhood memories. My childhood brain was a wild sparking mess, and my memories of that time are frightening crazy. I really tried to express how I see things in those stories.

Will you go back to writing any of those Jim stories? I really love them and others do too. I actually see quite a lot of parallels in the Frank and Jim stories.

Thanks for that, but I doubt I'll do more autobiographical work. I drew those stories out of a compulsion to get my experiences on paper, to present my case to the world, so to speak. I couldn't do that today with anything like the same drive and urgency. I don't take my experiences as seriously as I used to.

With the publishing of One Beautiful Spring Day, is there anything more to be said and done with Frank and his world? Will there be future adventures, or is Frank done?

I wonder about that myself. One Beautiful Spring Day makes some very final statements, and the urge to start a new story hasn't materialized. Since finishing the book I've made some large free-standing Frank drawings and I'd like to do more.

Do you still view what you did with Congress a mistake? It has produced glorious results.

Of all the questions you've asked that's the hardest to answer. I still remember how my blood ran cold when I realized that bringing Fran into the situation was a huge blunder and that Fran would have to be written and drawn to remove her. But even as I was laboriously copying those opening pages line for line in atonement I was thinking how interesting it all was, and I wasn't dismayed or upset by the way things were going.

When I drew the cover for the L'Association edition of Fran it depicted a shot from the microscopic realm in the face-planet where Frank and the Pups make their exit via rocket, and I put Fran hiding in the foreground... the implication being that though unseen by Frank she was still around, and maybe had been around since the beginning (as obliquely suggested in Congress of the Animals), and there was the suggestion that she was working on Frank's behalf in some way.

So it felt like a huge mistake at the time, and I still describe it as such, but I'm not sorry it happened. As to whether it was all pre-planned by the Unifactor, that feels like a stretch, but God only knows.

Woodring's paintings and drawings will be on exhibit in a solo show at the Vashon Center for the Arts outside of Seattle from October 7 to 30, 2022.

The post A terrible beauty is born: Jim Woodring’s <em>One Beautiful Spring Day</em> appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment