To look for a fig in winter is a madman’s act.

-Marcus Aurelius

When I was asked to write about The Strange Death of Alex Raymond (2021) by Dave Sim and Carson Grubaugh, I had never heard of Grubaugh. I knew Sim had created Cerebus, a 300-issue satiric comic, which lasted from 1977 until 2004, about an aardvark warrior but had read nothing by him beyond the first collected volume, at which point, being unfamiliar with the works being satirizing, I lost interest, missing out on subsequent collections which, I came to understand, were significant. I knew that Sim had become embroiled in controversies, including alleged misogyny and a problematic relationship with a young fan, but none had engaged me, so while I may not have had the ideal background for the assignment, I doubt many people have spent more time pondering SD than me. It stepped into my showers. It was there when I woke at 2:00 AM to piss.

I address solely its appearance in book form. Sim had begun writing about Raymond in glamourpuss, a magazine he turned out from 2008-12. But when its run ended, he left the "mystery" of Raymond's death hanging. I have avoided supplemental material available online.1 While scholars may squawk, I have eliminated the text’s ellipses, italics, and emboldenings when quoting it. Those that appear, unless otherwise noted, are mine.

On September 6, 1956, the newspaper strip cartoonist Alex (Rip Kirby) Raymond was killed when the Corvette he was driving crashed into a tree. The car’s owner, Stan (The Heart of Juliet Jones) Drake, who had been riding shotgun, had an ear nearly torn off and a shoulder dislocated. The two had been speeding uphill when Raymond attempted to brake for a crossroad, hit the accelerator instead, and launched them airborne. Or so, Sim writes early in SD, Leonard (On Stage) Starr said in an interview in the October 2012 issue of Alter Ego magazine, Drake, who’d died in 1997, told him. This double hearsay explanation set Sim speculating about what “strange metaphysical undercurrents” may have been at play.

“Metaphysics” is a word I don’t believe I have written once in 50 years of published work, but Sim can use it five times on two facing pages (76-77) without coughing on the smoke from any Gauloises in the room:

“[a] hard lesson in comic-art metaphysics”;

“would have calmed the comic-art metaphysics”;

“only one facet of the comic-art metaphysics”;

“lesson in comic-art metaphysics”;

“the metaphysical repercussions.”

This difference, along with my hard-earned C- in Philosophy I, made me feel even queasier about my suitability for my topic.

But turning to my handy philosophical guide–actually, Naomi Zack’s The Handy Philosophy Answer Book (2010)–I learned metaphysics are “general questions and answers about the nature of reality... what relations exist between different kinds of things, and the connections between the mind and the world.” Taking this definition into account, Sim’s working thesis is that “the creator shapes the comic art and the comic art... shapes the creator,” which I can go along with, and “in comic-art metaphysics: if you draw it, you own the metaphysical repercussions, even if you didn’t write it,” which seems more of a stretch. Still later, he will say that if an author “will write it -- he always wrote it -- -- always had written it, [and] it affects events in his past, which is... ...his present and which is... ...simultaneously... ...his future” (all dashes and ellipses in original), which seems a bit of... I don’t know... Hooey?2

From these premises, Sim finds in Raymond’s death a trail of connections extending back and forth in time influencing each other as they occurred/occur/will occur. But even a C- guy can tell you that connections do not always amount to consequences. That “A” precedes “Z” does not mean “A” caused “Z”. Nor does “A”, “B”, “C”... “Y” preceding “Z”. It may be fun thinking about this. Or it may drive you into a hut in the Black Forest or a nut house in Basel.

I am accustomed to being considered a rigidly narrow-minded thinker, but as an ex-P.I. lawyer, I would expect an investigation into a motor vehicle accident to begin with the police report. Then you maybe ask an accident reconstruction guy to consider tire treads, skid marks, road surface composition, angles of ascent or descent, the distance traveled before impact, mechanical malfunction. Sim took another path. He found an account of the accident in the Westport (CT) Crier a week after it occurred, which reported Raymond tried to brake for a stop sign, hit the accelerator, flew over a bump, and struck a maple tree 50 yards away. It did not mention a hill and said Drake’s only physical injury was a broken arm. Sim also found accounts from 1976, in which Raymond lost control of the car on a winding road and crashed into a stone wall, and from 1996, in which Raymond’s death was caused by a shard of glass from the windshield.3 And Sim states that “most accounts” had both of Drake’s ears torn off and surgically reattached,4 though no such surgery was accomplished on a human being until 1976.

Late in his book–sort of saving the best, or at least the first, somewhat inexplicably, for last–Sim reproduces the opening three paragraphs of an article in the Norwalk (CT) Hour the day after the crash. It said the Corvette “catapulted off a rainswept [sic]... road” - and that Drake’s injuries were a fractured wrist and possible fractured skull. When I obtained a copy of the entire article, I read that the Corvette had just passed an intersection when it “careened out of control,” ran across a small field, hit a tree 58 feet away, and “crumpled... as if it was made of paper.” So the account closest in time to the event mentions no attempt to brake. It suggests Raymond lost control of the car on a wet road while driving fast enough to total it on impact and makes Sim’s reliance on Starr all the more curious.5

Sim does not view these conflicting accounts as a lesson on the reliability of week- or 20- or 40- or 56-year-old memories. And while “metaphysical undercurrents” would not get you far in any court of law, he plunges into them. He calls the hit-accelerator-by-mistake theory “clinically insane” and its acceptance for half a century, “as mass schizophrenic episodes go... in a league all its own.”6 If the car was moving forward, Sim argues, Raymond’s foot had to have been on the accelerator and his flooring it a “murderously aggressive act.”

If the car was traveling uphill, which only Starr says it was, it is true that Raymond’s foot must have been on the accelerator reasonably close to any moment he tried to brake. If he lifted his foot to brake, he may still have hit the accelerator when he put it down. If the Corvette was traveling on flat ground or downhill, there was greater chance his foot was off the accelerator to begin with. But uphill, downhill, flat as the craps table on which Fate tosses every man’s life, if the crash was an intentional “murderously aggressive act,” rather than a careless one, who was the target? If Raymond wanted to kill Drake, this seems a risky and, in hindsight, manifestly inept way to go about it. If he was he trying to kill himself–making “suicidally” rather than “murderously” the more appropriate modifier–death by tree seems an equally bizarre choice.7 A question of motive seems to be pounding on the narrative door.8

Throughout, Sim drops hints he is about to let one in. Will it be the “barely repressed... hostility” Raymond had “incited within” Milt (Steve Canyon) Caniff? What about Raymond’s “decision to commit adultery” with an unnamed paramour? Does the then-nine-year-old Sara Jane Strickland, whose given names appear on a boat stern in a comic strip in 1952, and who will “prove to be the undoing of Stan Drake,”9 play a role? Susan Reed, a singer/harpist who materializes with Raymond in a publicity photo two weeks after he had “incarnated” her in Rip Kirby as singer/harpist “Melody Lane”, causing Sim to wonder if Raymond had, through “comic-art-metaphysical connivance... effectively designed his own future mistress,” sounds like a promising lead; but she is never mentioned again.

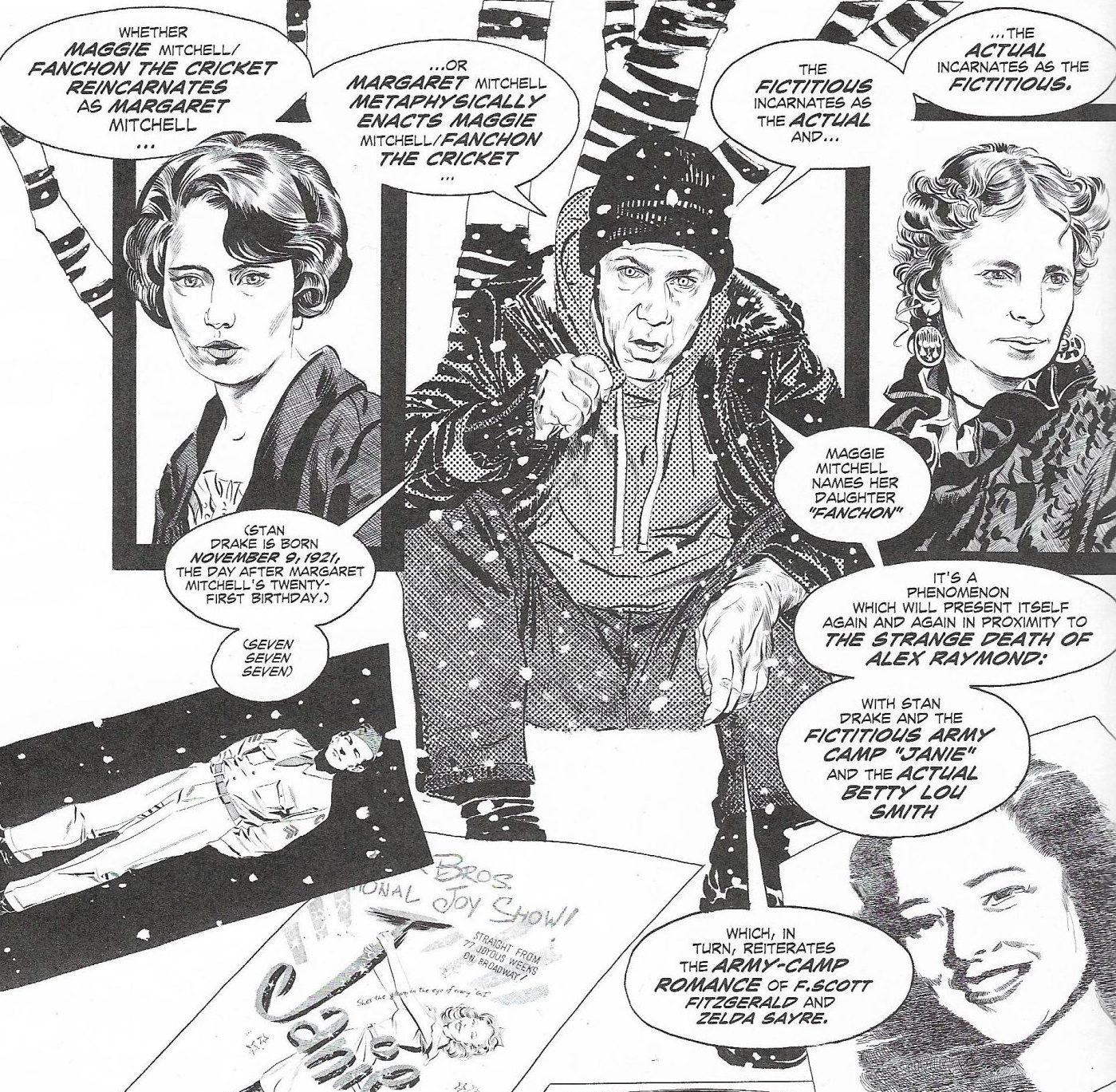

Just past halfway through the book, Sim concludes it is “almost” time “to examine the actual sequence of events... which led up to the strange death of Alex Raymond.” But first he needs to take a “closer look” at both Drake, which occupies him for 28 pages, and–a surprise guest–Margaret (Gone with the Wind) Mitchell, who occupies another 55.

Stan Drake had been an undistinguished comic book/pulp magazine illustrator whose good looks had landed him a movie screen test in late 1941. The film for which he was considered, Janie, released in 1944, featured a teenage heroine who seeks romance at a local army camp. After Pearl Harbor, Drake had enlisted, missing out on the movie but meeting his first wife at his army camp. This recalls for Sim that F. Scott Fitzgerald had met his wife, Zelda, at his army camp, which Sim terms “a central metaphysical jigsaw puzzle piece,” especially since Zelda died exactly 49 years (7 x 7, being a number of significance to Sim) before Drake, a piece which would fit more neatly if–as Google has it–Scott and Zelda had not actually met at a country club dance. And why Zelda’s and Drake’s dates of death carry more metaphysical weight than Scott’s or Drake’s wife is not explained. (The actress who played Janie, Joyce Reynolds, is still alive at 97, which may throw things further metaphysically askew.)

After the war, Drake became a successful commercial artist. But when his workload caused a mental collapse, a friend suggested he try the less stressful newspaper comic strip business.

Which led to Juliette Jones.

Which led to his Corvette.

Which led to Raymond leaving him lying beside it.

Margaret Mitchell’s connection to Raymond cannot be stated as succinctly.

For Sim, it begins with Mitchell (a) being both a “good” (proper family; Smith College) and “bad” (blacklisted from the Junior League; first husband a bootlegger) girl and (b) being run down by a speeding car in 1949. To make this relevant, from over 15 years of comic books and newspaper strips, Sim assembles a gallery of “bad” and “evil”–words he uses interchangeably–girls and women, as well as men and women (good and bad) killed or nearly killed by speeding cars and cabs and trucks and horse-drawn carriages. He treats these not as conventions or products of limited imaginations or caterings to what the dime-spending public will consume, but an “iconic comic-art metaphysical circle” orbiting Mitchell.

Lesser objects–sort of asteroidal debris–float in the atmosphere. Drake was born one day after Mitchell’s 21st (7, 7, 7) birthday; Mitchell wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald 21 years after meeting him; Fitzgerald worked 21 days on the GTW movie script; Oscar Polk, an actor in the film, was run down by a cab 7 months, 7 days before Mitchell’s fatal accident, and 10 days (not 7) after her 49th (7 x 7) birthday. Both Mitchell and Ward Greene, the writer of Rip Kirby, were nicknamed “Jimmy” after an early 20th century comic strip character of Jimmy Swinnerton’s; and the driver who struck Mitchell was rushing to visit his hospitalized son - “Jimmy”. If it seems Sim occasionally climbs out on a limb, well... from a 1947 romance comic he pulls an “amputated tree limb,” whose “metaphysical resonance” connected to the leg “severed” by an artillery shell resulting in the death of Mitchell’s fiancée in WWI.

Eventually Sim links over a dozen fictional women, several actual ones, and a United States senator (male) to Raymond’s fatal car crash, “an intricate... invocation/conjuration-metaphor, incarnating as an actual real world event,” which, even he concedes, “seems more a complete impossibility than a mere unlikelihood.” At least it would be but for the last comic book story he pulls from his sleeve, “Memphis Mae Corey”, an April 1949 tale of a “Dixie She-Devil” in Crimes By Women #6, the “most brutally exaggerated... of the 'bad-girl' Margaret Mitchell depictions,” whose ancestry includes a “Margaret Mitchell” accused of witchcraft in Ireland, the actual Mitchell’s “ancestral homeland.” Sim calls the story, also written (I think) by Greene, his “metaphysical lynchpin.” “Had Margaret Mitchell just been a contemporary iteration of an infernal presence in our world...” he writes, “caus[ing] the weird outbreak of Margaret Mitchell analogues in comic books cover-dated August-September 1949?” She was certainly “the start of a long, convoluted and malignant trail that leads, ultimately, to... the strange death of Alex Raymond!”

But to get there Sim needs more Ward Greene.

He and Mitchell had both lived in Atlanta. Both had worked for the Atlanta Journal, albeit two years apart. One of three Mitchell biographies Sim read described Greene as a friend of her second husband. (Sim suggests their relationship was closer, but that Mitchell’s estate’s refusal to let him quote from her letters prevented his establishing this.)

Drake told an interviewer in 1983 that when he looked into comic strip work, he was asked to submit something about two girls in a small town by an editor who knew Greene wanted to write such a series. In fact, Drake said, Green had been trying for 15 years to get Mitchell to write a “soap opera” for the Hearst newspapers, of which she had completed 30 pages–which no one seems to have seen–before she died. “They didn’t use those thirty pages Margaret Mitchell wrote?” the interviewer asked. “No,” Drake replied. (Sim finds this answer ambiguous. Did Drake’s “No” mean they didn’t or that, since it was a response to a negative, that they did?) Having trouble with the strip, Drake turned to the veteran writer Elliot (Big Ben Bolt) Caplin. Together, they produced The Heart of Juliet Jones, which debuted smashingly in March 1953.

Sim links Mitchell to Raymond because, in 1947, Greene, who was trying to goad her into granting him rights to a Gone with the Wind strip,10 introduced into Rip Kirby the “bad girl” Pagan Lee, whom he based on Mitchell. On May 25, 1949, "mere days" before he may have met Mitchell at Grand Central Station, Greene had Kirby re-meet Lee at Grand Central, and in yet another story that year, Greene even added a “Miss Mitchell” character, cementing the “fatal... metaphysical repercussions” for Raymond. (Sim also ties Raymond sans Greene to Mitchell via a 1940 comic book story he wrote whose hero, Keith Butler, bears the surname of GTW’s Rhett.)

Sim links Mitchell to Drake through Jones. Juliette, the “good” sister, is about to marry, leaving the “bad” sister, Eve, to look after their father, mirroring Mitchell’s dropping out of Smith to look after her’s. Promotional material for Jones was “evocative” of GTW’s. And the strip’s good girl/bad girl tension resembled that between Melanie Wilkes and Scarlett O’Hara. This would seem more probative if Mitchell had written the 30 pages of the untitled “soap opera” and if Drake or Caplin had seen them, let alone if Greene or Raymond had.11

Even so, the question remains: probative of what? In Sim’s formulation of comic-art metaphysics, it seems enough for an artist to have drawn something which connects to someone else for that drawing to have consequences for that artist. (Especially, presumably, if that someone is witch-connected.) You don’t need pre-existing pages of anything for that. And if here, “the spirit of Margaret Mitchell [was set] chafing at the false comic-art metaphysical portrayal” of her in the Greene-written Rip Kirby, perhaps giving her reason to go after Raymond, why should she rip off Drake’s ear and leave Caplin, let alone Greene, unscathed?

If you are dealing with, say, the JFK assassination, you have the observations of many people to build a conspiracy from. But because these observations have been absorbed within a few moments within an geographically limited area, they constrain you. Gunmen in windows or on rooftops or behind fences or on knolls. Puffs of smoke. With SD there is only Dave Sim–one man, one mind–looking at comic panels, looking and looking. The invitation to imagine and associate is open-ended and unchecked.

And about here–on and off the page–things became weird.

When Sim ended glamourpuss, he left the mystery of Raymond’s death hanging. The next year, Sim contracted with IDW Publishing to tell the complete story in a series of comic books. He began to redraw it, panel-by-panel, and to revise his text. In two years, he had completed about 180 pages before undiagnosed wrist pain brought him to a virtual stop.

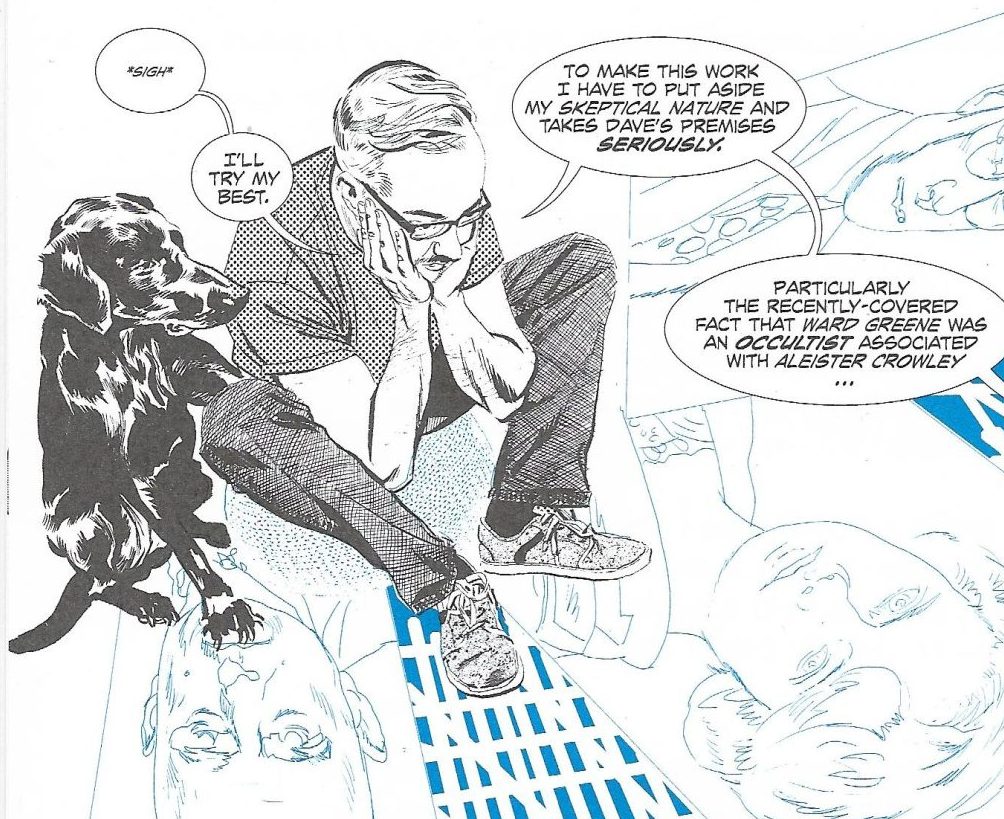

In 2016, Grubaugh, an artist, college art instructor, and fan of Sim and SD, offered to take over the drawing - and to await payment until publication. After seeing samples of his work, Sim accepted the offer. By year’s end, they had completed an intended Volume 1, with Grubaugh providing about 25 pages of “bridging material” involving a comic book store clerk named Jack, but Sim balked at publishing it.

Sim wanted to first repay $25-30,000 he believed he owed IDW. (The publisher, according to Grubaugh, denied being owed anything.) Sim wanted to pre-promote the book and raise money. By mid-2018, despite these diversions, a second volume was done, but Sim refused to publish it either. Grubaugh said he would do no more work until Volume 1 was released, so he would be paid.

About then Sim decided to visit every comic book store in California to promote SD. He would prepare a “test market” edition of Volume 1 to give store owners and those who backed a crowdfunding pitch of his. Grubaugh, believing Sim intended to claim this edition constituted a publication to induce him to resume work, insisted on a “wide release to [an] actual market.” At this point, mid-2020, Sim pulled the plug. He was wiped out financially. The story had become “impossibly huge.” If someone insisted on his wrapping it up, he could provide an 8-to-10-page narrative; otherwise, he was done.12

With Sim’s consent, Grubaugh took over SD, hoping to provide a finished book for all those who had been patiently awaiting one. Working from Sim’s notes and “roughs”–and adding thoughts and illustrations of his own–Grubaugh completed another 50 pages. When no publisher, including IDW, wanted it, Grubaugh and Sean Michael Robinson, who contributed additional art and lettering, published the hardbound, 324-page volume which reached me. These additions veered the story ever further from suburban Connecticut.13

The veerage commences with a relatively straightforward detour when, in the exact year of Alex Raymond’s birth, William Seabrook, a “future self-confessed cannibal... and lifelong obsessive bondage fetishist,” joins the Atlanta Journal, where he later connects with Greene over a mutual interest in voodoo; Seabrook would explore this interest in The Magic Island, a book with racist illustrations by Alexander King, whose name foreshadows Greene’s work for King Features, while Greene would treat Seabrook fictionally 21 years (7+7+7) later in his novel Ride the Nightmare, centered on a cartoonist modeled on George (Krazy Kat) Herriman, whose wife died in a car accident, whose daughter bore the same nickname as Raymond’s wife, who–Herriman, that is–had an affair with Jimmy Swinnerton’s ex-wife, and who, the exact year of Raymond’s birth, created five strips replete with sexual and familial “inversions” (a key word in this portion of the book), which are “either a comic art metaphysics pentagram... or a nearly unimaginably intricate five-fold metaphysical foreshadowing coincidence,” triggering both past and future events. Then Aleister (“The wickedest man in the world”) Crowley got involved.

As I said, “relatively straightforward” compared to what follows. The KKK; Leo Frank's murder of Mary Phagan; the comic strip characters “Derek Starlock”, “Honey Dorian”, “Lady Lilliput”, “Prospero Plunkett”, “The Mangler”, “Frisco Fritz”, “Bingo Julie”, “Circe Clayborne”, “Miss Mirabel”, “Margot Menke”, and “Mickey Mouse” (M.M. being such a “perfect palindromic" metaphor for the “Two Margarets,” good and bad, I half-expected Mickey Mantle to appear); two-dot (“I” in Morse Code) ellipses; Greene’s wife; Raymond’s wife; Raymond’s two daughters (with suggestions of, if not incest, child abuse); a harp in a panel of a 1947 Rip Kirby strip situated approximately six feet from a fireplace, which corresponds exactly to a treasure hidden six feet from somewhere in a 1950 strip; the deaths of Crowley and Greene both being attributed to respiratory ailments; Emma Hart, whose marriage exactly 165 years before Raymond’s death made her Lady Hamilton, whom Vivian Leigh portrayed in a biopic two years after playing Scarlett O’Hara; and–I forget how she got in here–Grace Kelly, who died from injuries in a car crash, like Princess Diana, who died exactly 57 years after Leigh married Laurence Olivier, and whose funeral was exactly 41 years after Raymond died.

Grubaugh’s ability to slip this mosaic together–and reach the moderately reassuring conclusion “Dave might not be just crazy”–was eased by his encountering en route two different “Carson”s in strips under consideration (though, I would point out, not a single “Grubaugh”), and by a woman he was dating getting–independent of his work–a tattoo of the Green Tara Mantra, which corresponded not only to Scarlett’s plantation (Tara) but a comic strip planet (Terra) ruled by women which Sim spent several earlier pages talking about.

I won’t spoil where Grubaugh comes out on Raymond’s death, but rumor has it Sim, funded by an anonymous donor, is preparing his own SD to refute it.

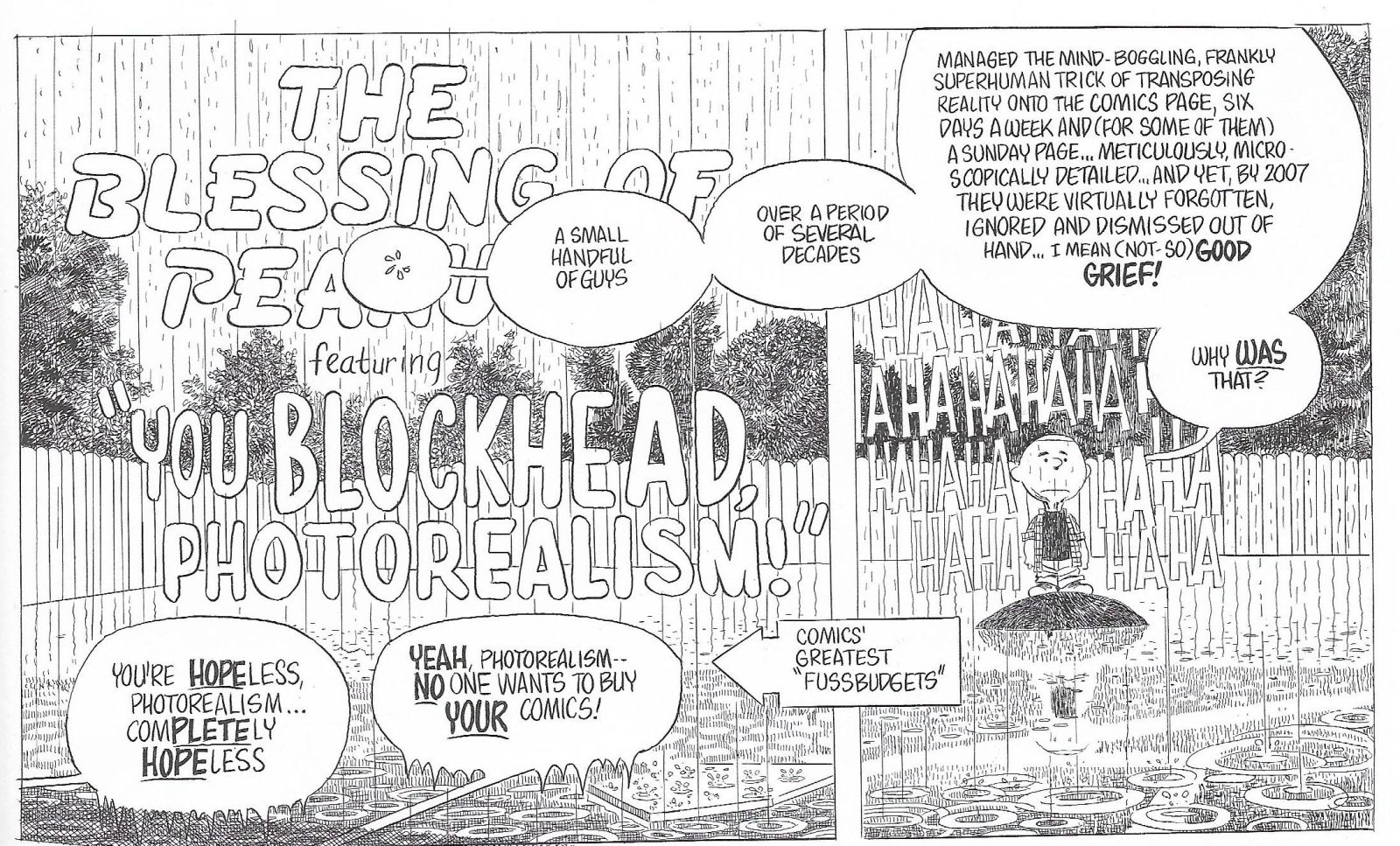

If SD often leaves you feeling you have been fending off an argument crafted by Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell on acid, it is not without value. Sim has grafted intriguing, informative digressions into 20th century futurism, 19th century theater and literature, 18th century history, and Greek myth onto his opus with at least the success of one of Dr. Moreau’s more companionable Beast Folk. The strongest part of the text–constituting the bulk of the pages Sim completed unassisted–is a fascinating, if idiosyncratic, study of the development of “photorealism” in comic illustration: “non-stylized”; “stylized”; “cartoon”; and “ultra.”

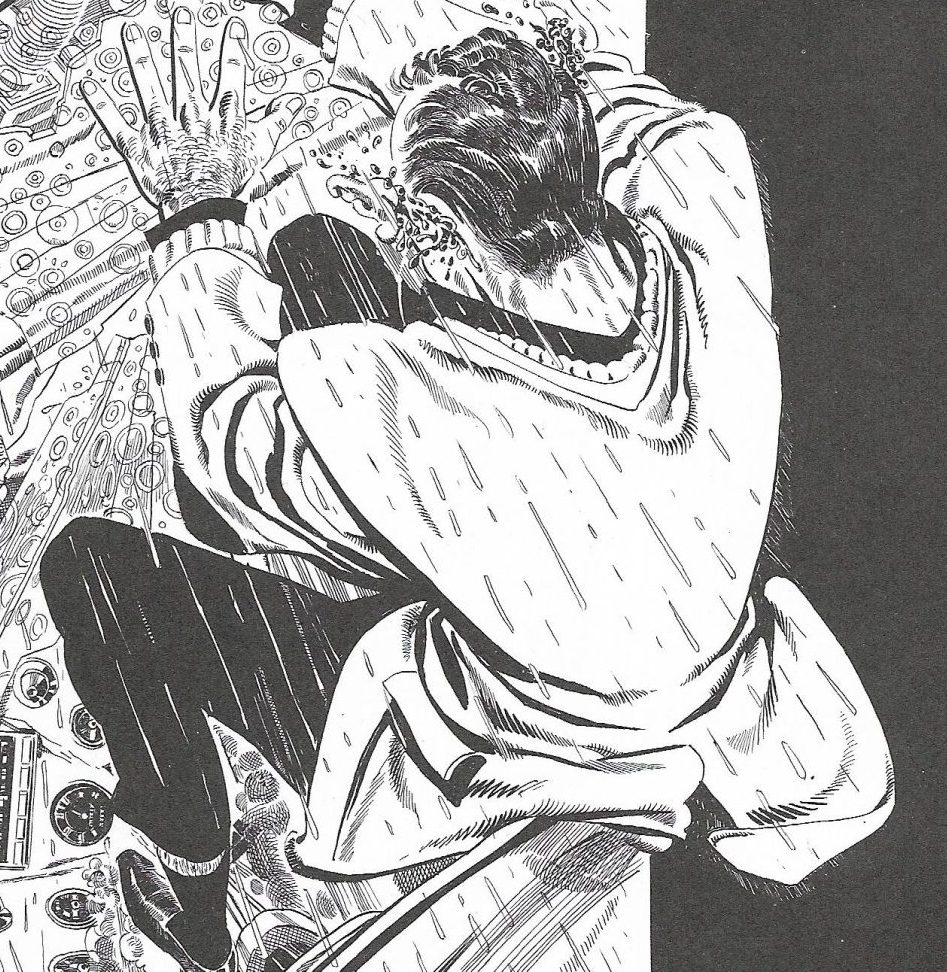

Sim pays tribute to each school’s leading practitioners: Hal Foster, Caniff, Raymond, Drake, and many of their disciples. He notes the movement drew upon influences ranging from Japanese calligraphy to John Singer Sargent to Edgar Degas in an effort to bring “high art” respectability–if a pre-20th century version of it–to the funny papers. He delves into the “how”s of their technique–the pens, the inks–the problems faced, and solutions found. The words-and-pictures nature of the comics medium allows Sim to simultaneously demonstrate visually what he is describing verbally - to “show” as he “tells”.

He has not simply reproduced panels of the artists he discusses. Utilizing his own considerable skills, he deftly traced those he wanted in pencil and inked them by eye. Panels that appear tilted in his book, of which there are many, he photographed at an angle selected to suit his overall design and then traced and inked them. And to illustrate the end of the photo-realist era, he drops a demeaning Peanuts, the minimalist comet which will extinguish them.

It lands like a spoiled egg upon the page.

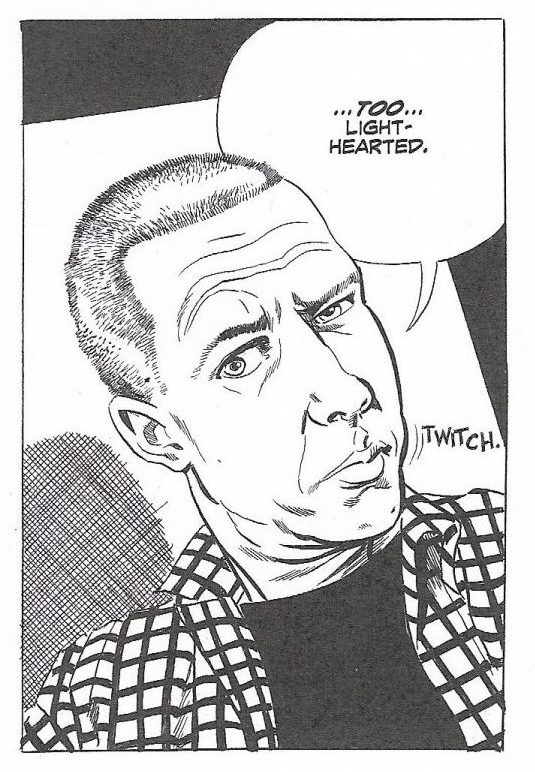

Sim is a dazzling draftsman. You can admire his drawings from breakfast through dinner and begin again the next morning. His faces radiate personality. His body language emotes. He adapts his style to fit the century–even the decade–of which his text speaks. The mastery of craft he exhibits commands respect for his ideas, even when they seem their flakiest. How can someone who can maintain such control, you ask yourself, be too far off his rocker?

His page layouts are also top notch. Their variety keeps viewing eyes alert. A panel may fill an entire page or a dozen panels may nest upon one. They may sit in tidy rows, rise and fall diagonally, or jumble like from a grab-bag picked. They may shift shape. Their borders may dissolve, allowing one drawing to enter another like a cellular creature in a feeding frenzy. Sim’s text may read traditionally left-to-right, row-above to row-below, or it may require tracking as it skews down, then up, then down again, arrows on a treasure map. The appropriated comic panels sometimes show as they originally appeared; other times their word balloons and captions have been commandeered by Sim (or Grubaugh) to serve as platforms for the case they are presenting. Portions of the story are told through portions of periodical articles or correspondence. It keeps you on your toes the same time it shifts the ground beneath your feet.

Sim and Grubaugh construct an equally seductive narrative form. In the first half of the book, each episode is inaugurated by Jack, the clerk, either reading a new issue of the SD comic, which has appeared from nowhere on her desk, or by having someone reading it outside her awareness. Events outside the store parallel those we are reading. These portions are heavily inked, lots of black, lots of night, snow steadily falling, all fostering the eerie atmosphere at SD’s core. The episodes themselves, while purportedly investigating Raymond’s death, flip back and forth between biography, career synopses, comic, cultural and (some) political history, critical and social analyses, and philosophical speculations. “Rabbit holes,” Sim terms them. “Layers upon layers.” All of a piece. All just out of reach. But we keep grabbing for them.

In her final appearance, Jack speaks directly to Grubaugh. She has realized he is drawing her, and since she had once been his student, this constitutes an invasion of privacy, if not abuse. From the beginning, Sim had also appeared as a character, instructing us, complaining to us, drawing conclusions we may agree with or not (and Grubaugh will do the same), so this is not a total surprise. But it is a step beyond. We know what a creator puts before us is the creator speaking, but a creator’s character speaking to him is an in-your-face demonstration of Sim’s comic art metaphysics at work. Readers may make of this exchange what they will, but they will make something. Marcel Duchamp said that art is a collaboration between creator and viewer and SD pushes and pulls the viewer’s mind the same way that the mind pulls and pushes it. The result is that for no two of us will the outcome be the same.

But...

Let’s recap.

In 2012 Dave Sim read an interview which described, in a way that did not make sense to him, a fatal auto accident that had occurred nearly 60 years before. He read other accounts of the accident, but he chose to believe that the 2012 version had been accepted by the general public due to its being gripped by a mass delusion, even though–I would guess–well over 90% of the public had no knowledge of this accident, and well over 99% of those who did had not read the interview which was the only place to express this version. Sim then began an investigation which consisted primarily of looking at comic strip and comic book panels, leading him to conclude that the cause of the accident centered on a woman who, as far as I can tell, never saw, spoke to, thought about, or had any dealings whatsoever with its victim.

It is hard not to entertain the possibility that Sim had returned to satire - and that conspiracies and believers in them were his target.

“Why did this death make such an impression on him?” Adele said, when I rambled on for the fifth or sixth time about the book. “What did he hope to get an answer to?” She put aside History for the moment. “What about you? Will this drive you insane or will it be a profitable way to spend your last decade? And can I make it through with you?”

When Sim began SD, he did not seem to know how it would end. He seemed to audition ending after ending but found each wanting. As he reached for an ending, his text wandered further and further afield. His references became more arcane, his visuals more diffuse. Even his metaphysical formulation plunged deeper into loopiness. He seemed to be performing an abstract expressionistic dance, flinging ink at paper and seeing what emerged from two-dot ellipses, run amuck vehicles; pin-up beauties, tie-and-jacketed gentlemen, the number 7, and present/past/future simultaneous do-ings.

Nothing did. His story got away from him with no maple tree to stop it. Did he ever know where he was going? Was Margaret Mitchell in his mind from the jump? Did he ever think, 'Hey, there is no mystery; Raymond simply drove too fast.' Sim wrote of Raymond that he had become enmeshed in a journey “into unexplored inner and upper reaches of ultra-realistic two-dimensional incarnation... [where he] would soon find himself completely subsumed and which would ultimately destroy him.” I think Sim sensed that happening to him.

The creator shapes the art. The art shapes the creator.

But who says you have to make sense? That stories must resolve? Strange Death is a grand book. Sit down; strap in; take the ride.

Normally, to investigate a motor vehicle accident, you look at the police report...

$2 gets you offense report 56633 from the Westport police department. It states that at about 5:13 PM, on September 6, 1956, a car traveling east on Clapboard Hill Road ran off the road at Morningside Drive, struck a tree, and flipped over. The passenger, Stan Drake, sustained a fractured left arm and possible fractured skull. The driver, Alex Raymond, was trapped inside with a fractured skull, fractured jaw, and crushed chest. No measurements appear to have been taken or estimates of speed made. The only witness, a driver proceeding south on Morningside, had been 100 yards from the intersection, when the Corvette crossed in front of him. A second later, he heard “a terrific crash... like an explosion.”

Drake spoke to the police 13 days later. He said he and Raymond had set off from Drake’s office about 4:00 PM. It was raining, so they “agreed to take it a little easy.” Drake drove for five minutes before giving Raymond a turn. He drove up Clapboard Hill in second gear at about 20 mph. He sped up, but “it was a safe speed for the day.” They went through the intersection without stopping, “and we bounced into the air, when we hit the crown of Morningside Drive.... I don’t remember too much except landing after the first bounce.... I don’t think our speed was over forty when we hit the crown...”

He did not mention an attempt to brake or a slipping foot.

What puzzles me is that, given the accident that occurred, Raymond was obviously not driving at a safe speed, so why did Drake clear him? It certainly was against his best interest. Even though it was Drake’s car, if Raymond’s negligence caused his injuries, Drake could have collected.

So what hold did Raymond have on Drake from the grave?

The Strange Absolution of Alex Raymond...

I hear its siren call.

* * *

The post A Fig in Winter appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment