The world of Anna Haifisch, populated with loopy anthropomorphic animals, where fine art and comix collide, makes it seem like anything might creep upon the page. Haifisch’s uninhibited style, a wry and spare approach owing something to Babar creator Jean de Brunhoff, serves her well in her cerebral observations.

We begin with the curious critter gracing the cover of her latest book. It’s a creature with stumpy paws and hollowed-out eyes, featured on a Warholesque can of some strange treat that looks like soda crackers. This sets the tone for the five short comics within. Each story has something to do with the absurdity of life. The strong existential bent to Haifisch’s work is fascinating and tends to avoid getting too dark. You could say that Haifisch has earned her world-weary view from life as a professional artist, mainly in Leipzig. It’s never easy to straddle between worlds, but fine art and indie comics share enough common ground. Some would argue that they’re both in the same boat; the trick to it all working out is dedication and a certain temperament.

I can’t stress enough to young aspiring artists how important it is to get your fingers dirty and create work. The results are in the doing, in the process. You can see it, page after page, in Haifisch’s work. Take "The Mouseglass", which I see as the book’s showcase story. You can enjoy Haifisch’s depiction of a crocodile chilling out on a couch, but know that it took numerous sketches and working out of ideas to get there. The theme is an excess of sophistication. The crocodile is part of an international conference pondering over various global concerns. The crocodile has reached its limit of delicate and ultra-polite exchanges. All that’s left is sneaking away to its hotel room and zoning out in front of a big screen staring at a bunch of penguins. That croc strikes an incredibly languid pose. Haifisch depicts a suite of understated elegance but undoubted opulence with its neat marble adornments and overflowing house plants. As is the case with each story, the narrative is one panel per page, which evokes a feel of a children’s book as well as cartoon gags, and etchings on a gallery wall.

Haifisch’s exquisitely simple work is so well thought out that it radiates a satisfying complexity. We see a whole world, not just a cast of quirky animal metaphors. After a while, I’m so absorbed in the work that I’m not even seeing animals to some extent. Each character is a unique being with individual and universal needs. The snake wants to eat the mouse, but Haifisch makes me believe in the snake’s loftier goals of international diplomacy. Kids get this. And Haifsich knows it. This is Babar for adults, right down to a similar lean linework and bright colors, mainly orange, green and yellow.

Haifisch sort of stumbled into making comics, having trained in printmaking. But once she dove into it, she built a distinctive and commanding voice across a flurry of work. A recommendation by the American cartoonist Alex Schubert inspired Vice to hire Haifisch in 2015 to do a regular online comic strip. That led to two English-language collections of The Artist, published by Breakdown Press in 2016 and 2019. She had already published a German-language graphic novel, Von Spatz, with Rotopol in 2015, which was released in English by Drawn & Quaterly in 2018. Von Spatz was a story about Walt Disney going into rehab to recharge his creative spirit, along with Tomi Ungerer and Saul Steinberg. In terms of longform books, that brings us to Schappi, published by Rotopol in 2019 and released in English this past June by Fantagraphics. The book offers Haifisch at the top of her game, as sardonic and otherworldly as anyone could hope for.

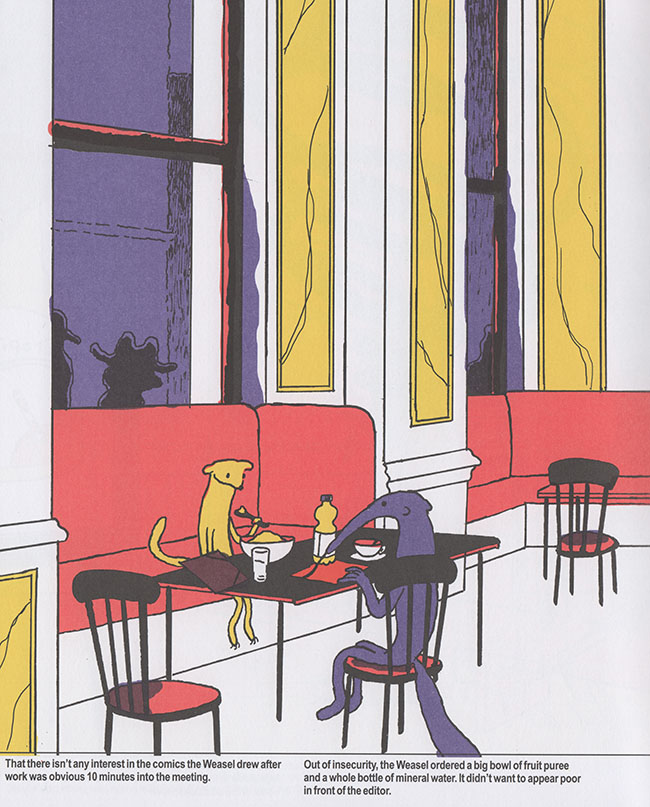

Two of the five stories are on Haifisch’s favorite theme, the capricious art world. She skewers everybody, including the artist! Artists can succumb to lazy habits, and all too often are dazzled by a world they know is less than kind. In the first story, "The Hall of the Bright Carvings", a reptilian patron of the arts gloats over the control it has over artists, who dutifully follow its orders. The reptile patron loathes the artists - and the artists, rather mechanically, present for review the most obvious of art. In the second art world story, "Letter to Weasel", a weasel frets over whether it made a good impression during a portfolio review for a magazine. It frets and frets. Finally, reaching home, there’s a letter from an art school. Rather mechanically, the letter informs the weasel that it has been accepted, and to please pick up its art as soon as possible or it will be destroyed. In both cases, this is totally spot on satire, crisply drawn with a perfectly understated and droll delivery.

Other stories find the animal characters closer to either natural or spiritual environments, and Haifisch does as well with a sincere tone as with a snarky one. In "A Proud Race", the life of an ostrich is beautifully examined. In "Fuji-san", the relationship between a dog, a squid and a rooster is given great meaning, like the spell cast by a puppet theater. Haifisch works her magic, remaining true to the moment, and bringing out greater truths besides. The best cartoonists need to be artists first. Not all cartoonists care to have a refined artistic sensibility, and some make it a point of not having one. Still, in the big scheme of things, comics at their most artful are the most engaging, timeless, and that is why I gravitate to Haifisch. If one is patient and embraces the process, anything is possible.

The post Schappi appeared first on The Comics Journal.

No comments:

Post a Comment